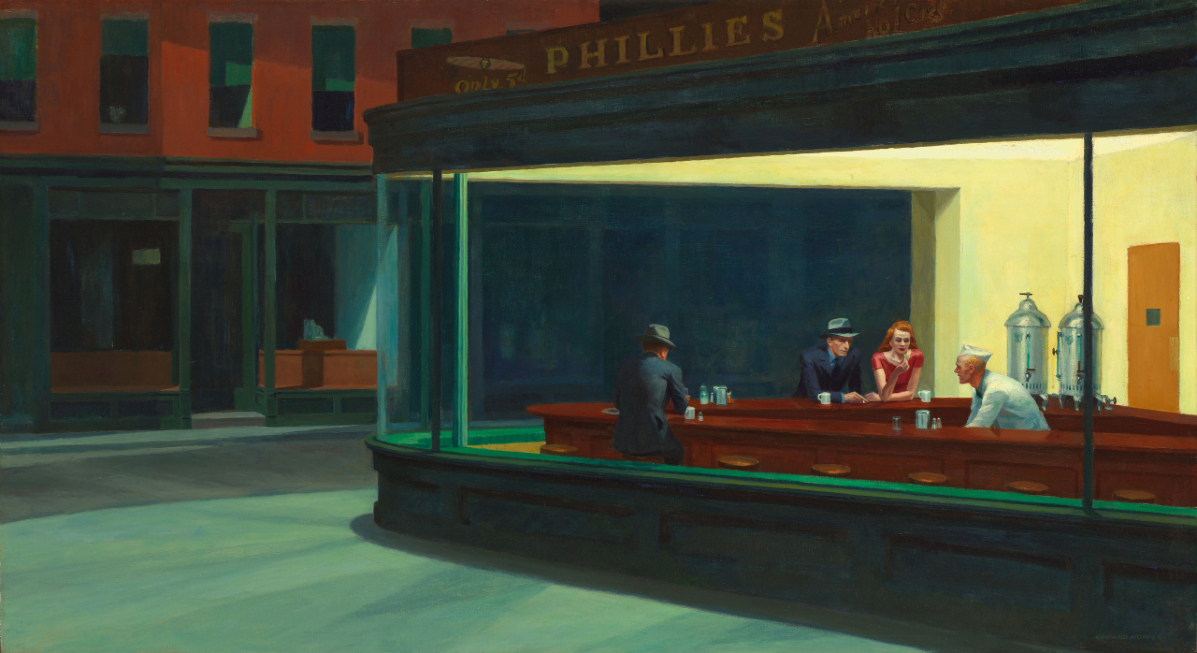

Aspects Of Loneliness:

A Hopper State Of Mind

“Silences talk to us.” Aileen Walsh turns to and finds parallels in Edward Hopper, ‘lyricist of isolation’, in contending with our current predicament…

Today is just like any other. The sameness is driving me mad. Even my walk by the river can’t ease the anxiety that eats away at my resolve to do something; to make this strange time mean something. Instead, I cling on for dear life, terrified I will succumb to the babble in my head. I find It difficult to reach out to others. Doubly difficult given a recently failed relationship – impossible under the confinements of a lockdown. In short, I’m lonely. Gut-wrenchingly so.

Caught in the lonely of an Edward Hopper frame, from which singular beings look out and nobody looks back. I turn away too. The aspect both isolates and threatens me but gaolers don’t lock us up and the prospect of release is not explored. Still, we stay. We are unwilling anchorites in our small frames. I fear we may be turning into petrified figures in a glass dome.

Many of us will feel the fear alone while searching inside and out to find purpose, inspiration; not wanting to acknowledge we have lost the habitual normality of living, of moving around freely. Insecurity is the new normal, and self-containment falls far short of independence. We are trapped.

I smile at every human. Their dogs, too. I wonder how I can get people to need me. Not in a “can I do your shopping?” kind of way (I am too exhausted for that), rather an “I miss you so much”, followed by a hug. What I could do with a hug. But it’s not allowed.

My state of mind turns like a kaleidoscope; Hopper, viewed through my narrow lens presents visions of single women in rooms, railway carriages, hotels, and dark cinema entrances that swallow them up. I look on.

His wariness only suggests possibilities. Alone, the figures give an impression of stillness; faces turned, eyes looking at something in the distance. The ambiguity that the artist introduces – that of the physical body, bare, open, displayed, female – hints at voyeurism. I study the figures, and continue as if a vigil must be kept.

Hopper once said: “Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world.”

I gaze at sparse, lonely landscapes that surround me. Pristine, unpeopled, shadowy invitations draw me in and, eagerly I, present and accounted for, follow, but I am confused by the empty space in me. Help. Please.

My psychology, recently bereaved, wants to inhabit a healthier environment, to hear chatter, have conversations. But just as I get my fear under control, nature locks me down. Now I need someone who can read my language when I am not talking. I am in empty rooms, getting tired and progressively mute.

My lover has gone, lukewarm and fleeting. I tried to be reasonable but managed only an angry, resentful silence.

In his book, On Becoming a Person A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy (1969), Carl Rogers wrote: “We think we listen, but very rarely do we listen with real understanding, true empathy. Being empathic is seeing the world through the eyes of the other, not seeing your world reflected in their eyes.” The assertion certainly carries some weight. The quote is a challenge to those of us who want connection but don’t know where to start.

What if the lack of connection arises from a deeper darkness? Olivia Laing touches on a category of loneliness which carries an added stigma: “The revelation of loneliness, the omnipresent, unanswerable feeling that I was in a state of lack, that I didn’t have what people were supposed to, and that this was down to some grave and no doubt externally unmistakable failing in my person: all this had quickened lately, the unwelcome consequence of being so summarily dismissed.”

I hear you.

This brings us to a different line of thought, albeit one intricately connected to the theme of loneliness. Laing travels into the area of real life, and the judgements of others as we move around in our loneliness.

Are places lonely or are we lonely in places? Edward Hopper painted all kinds of loneliness in all kinds of places. He even painted himself. Alone.

I am drawn back to the narrative in Hopper’s work, the underlying melancholy, which allows us to feel the isolation. There are no extraneous details, only lonely people in impersonal places. My awareness heightens my belief that he recognised what loneliness is. That he was lonely.

Hopper has been called the Master of urban isolation and a lyricist of alienation. Well-earned epithets.

If we look closely, what is not expressed is where the figure’s fragility lies. For example, in Nighthawks, we have a small gathering, but the characters are not engaged, rather, the façade of the bar provides the relief of space and contains the diners.

Hopper’s narrative arouses a plaintive echo of our loneliness; silences that talk to us. In the silence is the pain. Pain is in what we don’t attend to. We allow our silence to be hemmed in by isolation. The space beyond shapes us. Our fears may become the curators of our lived presence, our observed behaviours, our forgotten dreams.

Don’t let them go. We own one body and one mind. It’s all ours, and in the end it’s all we have.

What Hopper left is a narrative of images: strong, challenging, bright and inventive. Images that talk to us as we struggle with our loneliness. Keep going. Can I find a counterbalance to my inertia? Perhaps.

Remember, we win sometimes.

Aileen Walsh

This article is part of the series Next Chapter, a new writing project in partnership with Writing on the Wall, to nurture and publish new voices.

Image: Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, 1942. From: The Art Institute of Chicago, Fifty-third Annual Exhibition of American Paintings and Sculpture. Chicago: 1942.