Liverpool Biennial 2021 Public Realm – Reviewed

With the postponed Liverpool Biennial now underway, Mike Pinnington set off in search of meaning, and five new public realm artworks…

As you’re no doubt aware, this week marked a full year since England first went into lockdown. It has been twelve months of uncertainty, and worse, which has seen life as we knew it change – perhaps for ever. Now, as we begin to think about slowly and cautiously emerging from the restrictions necessitated by the global pandemic, we can think about leaving the front door with a purpose and a destination in mind.

For some residents of Liverpool, that may have already occurred, as the city’s Biennial was declared open to local visitors from Saturday (20 March). Postponed since its intended 2020 opening, this Biennial has commenced with five public realm artworks dotted around the city centre to discover. In addition, a number of sonic and digital commissions by Ines Doujak, KeKeÇa and UBERMORGEN are available to access via an ‘Online Portal’, with the promise of a ‘free and evolving programme’ coming between now and the end of June.

So, grabbing the opportunity to make meaning of my weekend, I set off on the trail of the quintet of new works. The first thing I encountered, though, were life-size sculptures of people immersed in the digital worlds found on their phones – part of the city’s River of Light festival I worked out later. (Red herring it may have been, it was an interesting primer for the day, provoking questions around what a festival of contemporary art versus a ‘local’, city led celebration like River of Light, looks like.) The first Biennial work on my route was Rashid Johnson’s Stacked Heads (2020) at Canning Dock Quayside – unfortunately, due to the installation of another work in the aforementioned River of Light, I couldn’t get near it. A sign on a wire fence told me the site would be accessible from Monday 22. After months of Covid related postponements, I suppose I could handle a few more days.

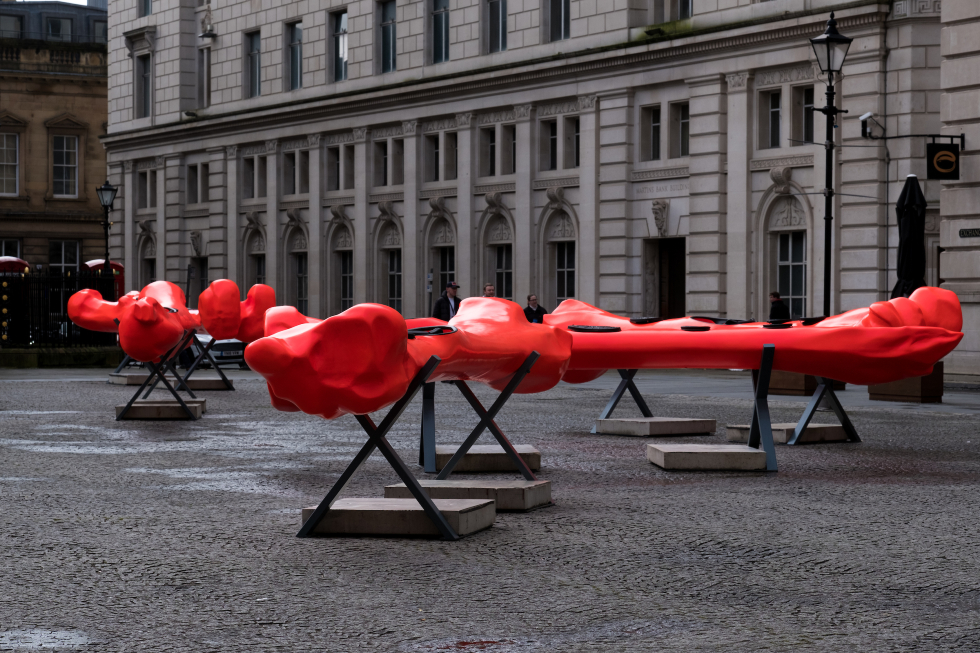

Undeterred after this double false start, my next stop was Exchange Flags, linked forever to Liverpool’s ugly role as the slave-trading capital of Britain. It was here that merchants of the city – among them, slave traders – carried out their business. The expanse also houses a permanent Admiral Horatio Nelson statue; complete with skeletons and mournful figures, it’s said to represent prisoners of war held here during the Napoleonic Wars. Scattered around it currently are several red forms which, as you approach, reveal themselves to be bone shaped sculptures.

This is Teresa Solar’s Osteoclast (I do not know how I came to be on board this ship, this navel of my ark) (2021). The objects are, in fact, kayaks, bringing forth ideas of precarious journeys necessitated by famine, conflict, and other trials beyond people’s control. This link is confirmed in the nearby text panel, which emphasises the fragility of bones and small vessels out on the open seas, used as desperate ‘vehicles of migration’. Made especially poignant by its setting, and the turning of the screw of new plans for immigration, Solar’s work is timely and thought-provoking.

From the business district, I made my way into town proper, and to shopping mecca Liverpool One, busy despite the lack of open shops, in search of Linder’s Bower of Bliss (2021). Nearing national treasure status, Linder Sterling made her reputation with – and remains well remembered for – the artwork for Buzzcocks’ 1977 single Orgasm Addict. Since then, her satirical works drawing on the DIY aesthetic and attitude of the post-punk scene from which she emerged have established her as a fierce and effective critic of the patriarchy and the representation of women. It is with some regret, then, that I must report that Bower of Bliss, lacking Linder’s usual punch, falls well short of expectations.

Somehow, the typically sharp-edged aspect of her work has been smoothed away here, reduced to a kind of snap-shot pastiche of what the wall text speaks of as blossoming life and joyous celebration, of shopping, beauty and Liverpool pop culture. We see lipstick, flora, and fauna; a seagull rears its head and, somewhat on the nose, there’s even a snippet of a Beatles record sleeve. In the centre-left of the work is a figure, their intestines exposed, responding a little obviously to the Biennial’s theme/title, The Stomach and the Port. When the promised indoor segment of the festival opens, examples of the artist’s back catalogue are due to be displayed at Tate Liverpool; Bower of Bliss will fair badly by contrast.

Underwhelmed, I make my way to Bluecoat, whose outside wall hosts Jorgge Menna Barreto’s mural Mauvais Alphabet (2021), made in collaboration with students from LJMU. A work about ‘what we eat and how we live’ – literal interpretations are the order of the day, it seems – the colourful mural depicts weeds common to the city. The resulting mural is decorative at best: pretty flashes of colour and form at the eyeline’s periphery as we make our way from one part of the city to the next.

Thank heavens, then, for Larry Achiampong’s Pan African Flags For the Relic Travellers’ Alliance. Taking up positions at vantage points across the city, they represent the 54 nations of the African continent, with Achiampong selecting the colours green, black, red, and yellow gold to signify, in turn, the land, its people, their struggles and hopes for the future. The flags’ flurry of colour and context – social, historical, political, cultural – provide a welcome, not simply aesthetically pleasing, relevant hit. At the Cunard Building on Liverpool’s waterfront, one of them is juxtaposed with the Union Flag and, in the context of the Tories’ disconcerting flag obsession (complete with stale whiffs of empire), their relevance is turned up to eleven.

They seem to demand answers, to questions including: who stands in front of flags and to what end? Is it to divide (and to remind us of shameful historical conquests), or to bring people together? The key word in their title is ‘Alliance’, and the artist’s intent is that they symbolize unity, previously describing them as “beacons of hope”. A message we can surely all find solace in right now.

Mike Pinnington

The ‘inside’ segment of Liverpool Biennial 2021 is currently scheduled to begin in May at venues across the city. The festival of contemporary art continues until June 2021

Images: Pan African Flag for the Relic Travellers’ Alliance (2021) by Larry Achiampong at the Cunard Building. Photograph by Mark McNulty; Bower of Bliss (2021) by Linder at Liverpool ONE. Photograph by Mark McNulty; Osteoclast (2021) by Teresa Solar at Exchange Flags. Photograph by Mark McNulty