Bearing Witness: Don McCullin at Tate Liverpool – Reviewed

Don McCullin’s career, celebrated in Tate Liverpool’s retrospective exhibition, reads like a document of key 20th Century events. Armed with her Student Art Pass, granting 50% off major exhibitions, Hazel Maria trains her lens on the iconic photographer’s work…

Don McCullin’s reputation precedes this exhibition like the brawny black horse that drags the funeral carriage. Now eighty-five, the decorated photojournalist’s assignments and assorted personal pilgrimages are currently on display in Tate Liverpool’s retrospective exhibition, across more than two hundred photographs made over the course of half a century. Do expect difficult scenes, unflinchingly depicting violence, death and displacement. These are not strictly art works, but documents; as such, McCullin concisely names them for subject matter and year.

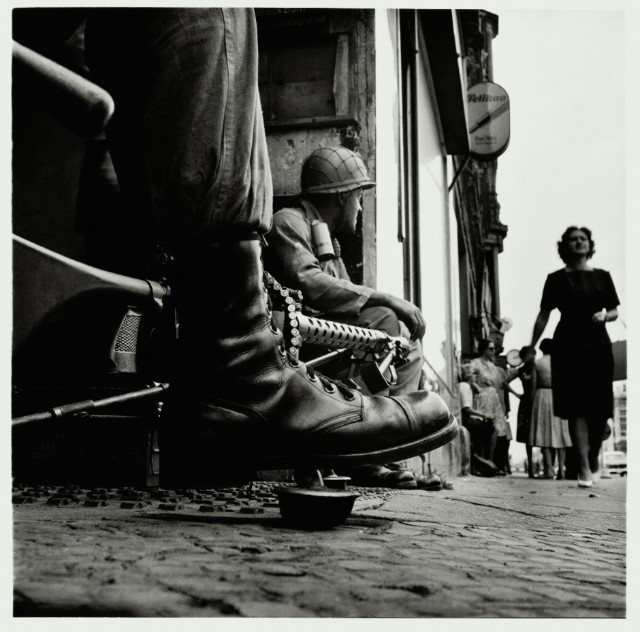

In 1961, soldiers eye each other on the site for the soon to be constructed Berlin Wall. People holding their shopping look on, a woman raising a hand to wave. In an exceptional composition taken near to Checkpoint Charlie an elegant woman cuts an hourglass figure walking down the road; to the left a giant black boot and an abstracted gun. Why has this never been an album cover?

Onwards. A well-dressed woman is carried away from a 1960s anti-fascist protest in Trafalgar Square. A little boy sits cross legged on the pavement and smiles at a cat in London’s East End in 1962. Definite characters begin to emerge here under the scrutiny of McCullin’s lens, inviting us to read these people, like books. I know this is London, and I know this little boy is dirt poor. Such images feel like a buffer before your exposure to those of Biafra between 1968 and 1969.

Known today as the Nigerian Civil War, images from the humanitarian crisis that resulted from the conflict are… hard. Here, the photographs’ matter of fact titles seem to pre-empt and temper extremes of response. Starving twenty four year old mother with child, Biafra (1968). A beyond gaunt and hollow-in-every-sense young woman holds a child trying to feed from withered breasts. Sombre proof of the finite tolerance of the human body to starvation.

In Murder in a Turkish Village (1964), a woman looks down at the pool of blood surrounding her husband holding a patterned scarf with which to cover the corpse. I lift my phone to take a photo, the little yellow boxes of facial recognition do their uncanny work, framing the crying widow’s expression, who is hunched over her dead husband. I really shouldn’t have done that, I thought, realising I don’t have the right to make or share a cheap reproduction of her pain in that moment.

It’s worth mentioning here, therefore, that issues around the white male gaze paired with concerns of the ethics of war photography could overshadow individual narratives, and the exploration of McCullin’s career. Tate, wisely, does not shy from the West’s involvement in many of these conflicts and includes McCullin’s own voice, taking the form of quotes interknit throughout the exhibition, on walls and labels. The sacrifice McCullin himself has made (and continues to live with) to capture these scenes is considerable, his images having travelled back to Britain to shock and inform readers of the Observer and the Sunday Times. “Was I of any use at all to the Biafran people?” he asks – us or himself?

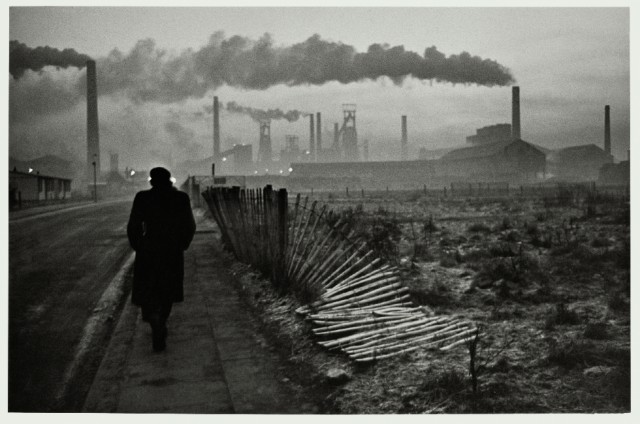

The heavy atmosphere lifts in the next room where the North is made mythic. Skies hearty with billows of black smoke and rows of staunch terraced houses. Figures pull and push. A cart full of scrap, a wheelbarrow full of washing. A baby. Secretly, this is what I came for. The photographs here are the flesh on the bones of stories of post war Liverpool my parents would repeat, even after I got sick of hearing them. Seeing these people feels intimate and familiar.

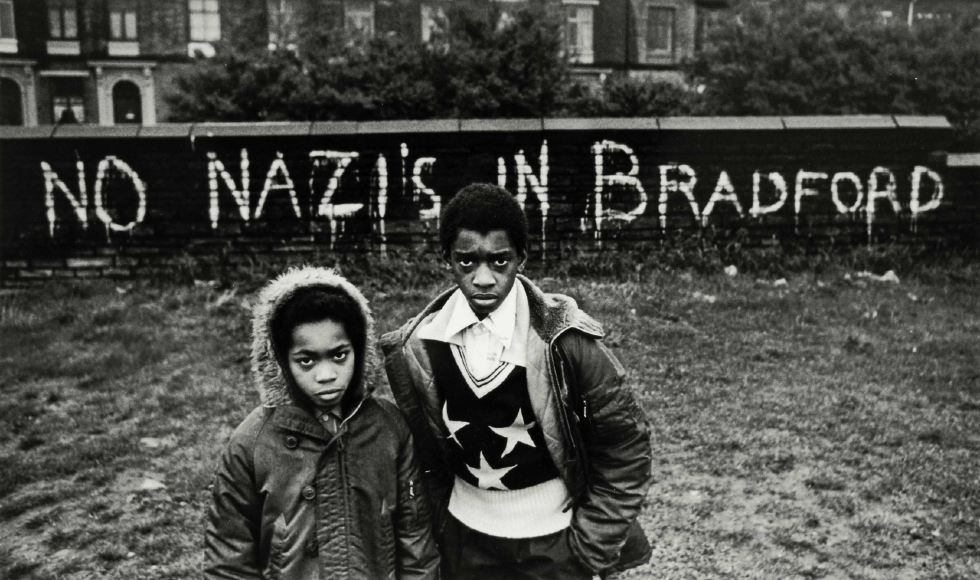

The deindustrialisation of cities like Bradford in the 1960s and 70s meant mass unemployment and poverty, and slum clearance in Liverpool left the streets looking like militarised zones. In the gallery too, an older couple – masked up and bending into photos, hands brushing and entwining – giggle at the image of a scampering young lad in Liverpool 8 fifty years ago. Might they have known this boy? Might you?

Miss Wade, from Bradford (1978) is standing with her arms crossed and gaze lowered, her skirting board black with rot. There’s a cheeky glint in the eyes of children sat upright in their beds, wallpaper behind them streaked and flaking, the itch from their wool blankets made palpable. I sense genuine affection from McCullin for these subjects, but still he has not allowed them to escape the war zone treatment. Cold matter-of-fact tonality comes from the black and white, meaning no detail can hide in the mid tones.

Sparks of hope fly from some frames, however. Moments of pure giddy humanity, trapped in McCullin’s shutter like an anxious fly. A photograph of an aging Bradford couple in 1970 enjoying a cup of tea in a café, just on the verge of smiling. Everyone’s getting on with it. A sturdy woman is buying a new shovel, and others buzz about a car boot sale.

Vietnam, Cambodia, Lebanon, Bangladesh, Iraq, and India follow this interlude. At this stage in the exhibition the knowing between place and time, between conflicts and different political eras of human cruelty, has blurred. A Palestinian mother in her destroyed house, Sabra Camp (1982). Wires and rubble surround a wailing woman. Christian Phalange gunmen in the Holiday Inn Hotel, Beirut (1976). Two folded figures kneel on the floor under a chandelier, holding guns and avoiding counter fire. Dead Cambodian Soldier and young grieving widow, Phnom Penh (1975). Flat on a table with his eyes closed, a vacant woman sags on to his chest.

Palmyra’s ancient ruins are being destroyed by the so-called Islamic State. The Syrian civil war is ongoing. Travelling to what was once the southern border of the Roman Empire between 2006 and 2017 for the project Southern Frontiers, McCullin has photographed skeletal temples and the remains of arches and columns as they cast solemn shadows on the ground. Somehow wise to their sad situation. The both natural and destructive decay of Palmyra’s ruins mirror Homs, Syria (2018). A rebel stronghold, Homs was seized by the Syrian government, resulting in absolute destruction. Here the modern buildings look to fold like paper, staircases exposed and whole floors bowing to gravity.

You might feel a heavy realisation that nothing has really changed. Looking through McCullin’s lens back in time only reveals the cyclical nature of war and displacement. To feel empathy is a burden of the human condition, for want of a better cliché. But in the case of this exhibition, to lower the head in recognition of the depths of human brutality, and to leave haunted by the sight of a dead body with his brains scattered next to him, while scarcely enough, is all we can do. To bear witness and suffer a drop of what McCullin has for a lifetime is ultimately the point.

Hazel Maria

Hazel visited Don McCullin at Tate Liverpool prior to the current lockdown. The exhibition continues when the gallery reopens

Student Art Pass: make 2021 a year to remember

2020 may be a year worth forgetting but you can still make 2021 one to remember with a year of art + opportunities for just £5.

A Student Art Pass lets you dive into culture on a budget with free entry to hundreds of museums and galleries across the UK, and 50% off major exhibitions – from Design Museum to V&A Dundee. Plus, you’ll gain access to paid opportunities in the visual arts and grow your network by joining the #WeAreArtful @StudentArtPass community. All for just £5 a year.

Because of lockdown this month, we’ve extended the expiry date on all Student Art Pass purchases to December 2021. So, you’ll have a full year of cheaper art experiences waiting for you next year when you buy a pass today.

But hurry! The pass is available to buy for £5 for a limited time until 13 December – don’t miss out, get yours today.

Images, from top: Local Boys in Bradford 1972 © Don McCullin; Near Checkpoint Charlie, Berlin 1961 Tate Purchased 2012 © Don McCullin; Early shift, West Hartlepool steelworks, County Durham 1963 © Don McCullin; Bradford c.1970 © Don McCullin