“We’re experts at taking risks.” On the fraught issue of artists’ pay

Is being an artist now so precarious as to be unhealthy? Sue Flowers draws on her own experiences and those of others working in the sector to consider what more can be done…

Having worked as a freelance artist all my life, there are many adjectives I could use to describe it: interesting, diverse, thought-provoking and challenging are a few. Recently, however, I would add unhealthy to that list, due to a growing sense of unease that things aren’t quite right for artists. Something fundamental needs to change if we are to survive.

My own career began in the late eighties, and subsequently, with my partner and fellow artist Pete Flowers, I established Green Close, a rural arts organisation based in North Lancashire that specialises in social development. We’ve had an amazing journey and been fortunate to commission and work with artists from around the world: but one thing that has been overwhelmingly consistent for us, has been the amount of effort we have needed, both to sustain the organisation and our own practice as artists.

Running an arts organisation that is geographically so outside of visual art infrastructures has meant we have had to be responsive to social needs and be creative in our approach to fundraising. We have worked with environmentalists, educators, historians and healthcare workers. On occasion, Arts Council England (ACE) have helped with project funding, enabling us to deliver more ambitious programmes – such as Viva Mexico (2007), which brought Mexican ceramic artists to our studios, and the Lancashire Witches400 project (2012), which explored the history of the infamous Lancashire witch trials of 1612 and what this means to us today.

Things dramatically changed for us due to the ill mental health of a close family member in 2013. We wondered how we would survive as freelance artists leading an arts organisation dependent on project funding, when we turned our lives towards caring and support. Times were pretty tough back then, but we diversified, worked to our strengths, counted the pennies, and I took up a role in mental health research at Lancaster University.

At that time, I didn’t know that I could do anything else other than be an artist. I felt a sickening sense of guilt in my stomach, like I was leaving my best friend at home while I went off on new adventures.

It turned out that research wasn’t particularly easy, but I learned that I had lots of transferrable skills, that I was actually good at what I did, and that I could use my creativity to see around and outside the boxes that so many others seemed to dwell within. Most importantly it gave me the time to reflect, to be paid when I felt sick, to understand the importance of research, and ultimately conclude that working as a freelancer in the arts for over thirty years had led to a pattern of unhealthy over-working.

I came back to the precarity of being freelance this April – just weeks after the British government announced a Covid-19 lockdown. It could have been disastrous, but thankfully I dug deep into my resilience, put memories of unsuccessful bids to ACE to the back of my mind, and applied for their Emergency Relief Fund grant for artists and organisations. By the end of it I was almost on my knees.

As artists we are experts at taking risks, experimenting and using failures to grow. But I knew that if this didn’t pay off it was going to be a very bleak future ahead. At Green Close we proposed to deliver The Phoenix Project, an online mental wellbeing programme delivered by twenty-three artists. While filling in the online application form, I enjoyed imagining my metaphor of a mythical bird rising from the ashes of more than twenty-four years of hard, exhausting work.

Miraculously the effort paid off – and it genuinely felt like a miracle. We were granted the money for The Phoenix Project and could continue running Green Close, and to boot, I received my own grant award as an artist.

It is hard to describe that knife-edge we were on earlier this year. It was scary as hell, and this time it felt like that old best friend was about to have her life support system turned off. At the time I was shocked that after over thirty years of working successfully in the arts I was so near to thinking that maybe this was going to be the end. I began to wonder about being so close to the edge and how others with less experience and, perhaps, resilience, had coped.

I spoke with artist Danielle Chappell-Aspinwall, who is midway through studying for an MA Fine Art Projects for Places course at the University of Central Lancashire. She explained that she has taken a pathway not dissimilar to many other artists, taking on different commercial and freelance roles to sustain her creative practice, and that “the whole world just crashed down big-time” upon her when the pandemic arrived.

After months of working (unpaid) with communities for Barrow’s Beautiful Places – an art event celebrating nature reserves, paths and other sites of natural beauty in the borough – her community exhibition was unable to go ahead at the Town Hall. On top of that, stockists of Chappell-Aspinwall’s work closed, so she had no income from product sales and no way of paying for childcare for her young family. Covid-19 meant there was no exhibition, no funding, no work, and the future was grim.

However, with encouragement from the Cumbria Arts and Culture Network, Chappell-Aspinwall also applied for the Artists Emergency Relief Fund; not only has it saved her as an artist, she told me, but with the mentoring that it enabled, she thinks she may be better equipped to apply to ACE in the future. But should it really take a global pandemic to expose the precariousness of how artists make a living?

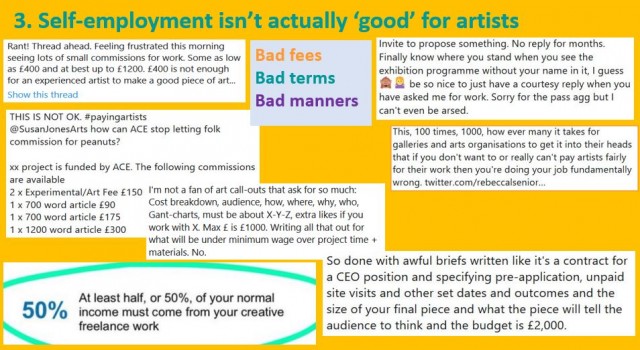

Clearly not, according to writer and researcher Susan Jones. Jones is well versed in the challenges, reality and nuances of trying to sustain a visual arts practice, having worked as Director of a-n, the artists’ information organisation, until 2014, and having supported numerous professional development programmes for artists. Jones, who has recently completed a PhD exploring in detail artists’ livelihoods and their relationship with arts policy, has been prolific in authoring evidence-based articles about why funding for individual artists is so important, and what needs to happen to ensure their future economic survival.

I ask Jones how hope and opportunity can be embedded into the future lives of artists and she replies, “not by waiting for some funding body to throw a few crumbs”. So I wonder what she thinks should happen now? “Why can’t the Arts Council say, actually, let’s have a pause and think about what is important about the arts for society and ask,” says Jones, “if we were starting from scratch how would we deliver it? Perhaps there are better ways of doing things.”

Jones has recently submitted a report including recommendations to the DCMS (Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport) calling for arts policy to redress the marginalisation of independent creators. “It’s not a re-set we need”, Jones says, “it’s a re-boot.” She is calling for a diversification in how arts policy is made and delivered, the democratisation of arts development and decision-making frameworks, and a devolution that would take a substantial amount of money away from the national arts infrastructure forever.

Artist Sally Slade Payne, who has been teaching and developing her practice for forty years, thinks the solution would be “to create a new fund for innovation, enabling new thinking and new ways of delivering across all creative areas.” Teaching was always Slade-Payne’s main source of income, alongside a small amount of freelance work. She comments, “Working as a freelancer in the arts has always been precarious, more so now than ever”.

Having had a lifetime experience working in the arts, I asked Slade Payne about future creative opportunities. “I think navigating the future will change and move as we go forward. The world feels unstable and fragile, finding a different way of relating, connecting, empowering is our challenge”. However, she felt confident that young artists and recent graduates would be able to do so, despite the current Covid-19 situation. I wonder, however, whether this means that they will have to work harder for less revenue than their predecessors.

Whatever happens to the arts and its funding systems, all four of us agree that something new and radically different needs to happen to enable artists to survive.

In practical terms, and specifically in the North West, this would mean organisations like the Contemporary Visual Arts Network (CVAN) doing more to ensure that the voice of the individual artist is respected, listened to and heard in equal measure alongside larger galleries and arts institutions. CVAN is currently developing a Visual Arts Alliance – alongside a-n, Artquest, AxisWeb, Creative Workspace Network, Curator Space, DACS, and International Curators Forum – to ‘build back better’ and ‘address inequalities, the climate emergency and the imminent economic hardship that will be faced by many.’

The issue of paying artists fairly will not go away without a shake up of the current system. We need to make sure that budget holders are paying artists to be the creative leaders they so often are, and that we safeguard professional practice by changing arts policy to support them. This will enable the criticality of new thinking and ways of working that we so desperately need in such challenging times. Jones calls for policies that can be “local, structural, co-validating, participatory, inclusive and long term”. I agree; this is not just about arts policy, but also about how we choose to spend our lives and creative energies. We need to use our time wisely to ensure artists can not only survive, but also thrive, because now more than ever our communities need us.

Sue Flowers

Images, from top: Viva Mexico engagement workshops at Green Close with Israel Soteno & Sue Flowers 2007; Sue Flowers working at Green Close, photo Darren Andrews 2012; Isolation Booth by Danielle Chappell Aspinwall 2020; The self-employment myth from the presentation ‘Exploding myths: the future of artists’ livelihoods’ by Dr Susan Jones 2020

This article is part of the series, ‘New Critical Writing North West: Voices on Lancashire & Cumbria’: new pieces of critical writing which will review and examine issues relating to the contemporary visual arts in Lancashire and Cumbria. The series has been commissioned by Contemporary Visual Arts Network North-by-NorthWest (CVAN NbyNW), and a new feature will be profiled on The Double Negative each month until October 2020.