Don McCullin – The Sublime amid the Maelstrom

Don McCullin’s has been a career spent documenting anguish. But, finds Mike Pinnington, his lens is equally capable of capturing quotidian, humane scenes…

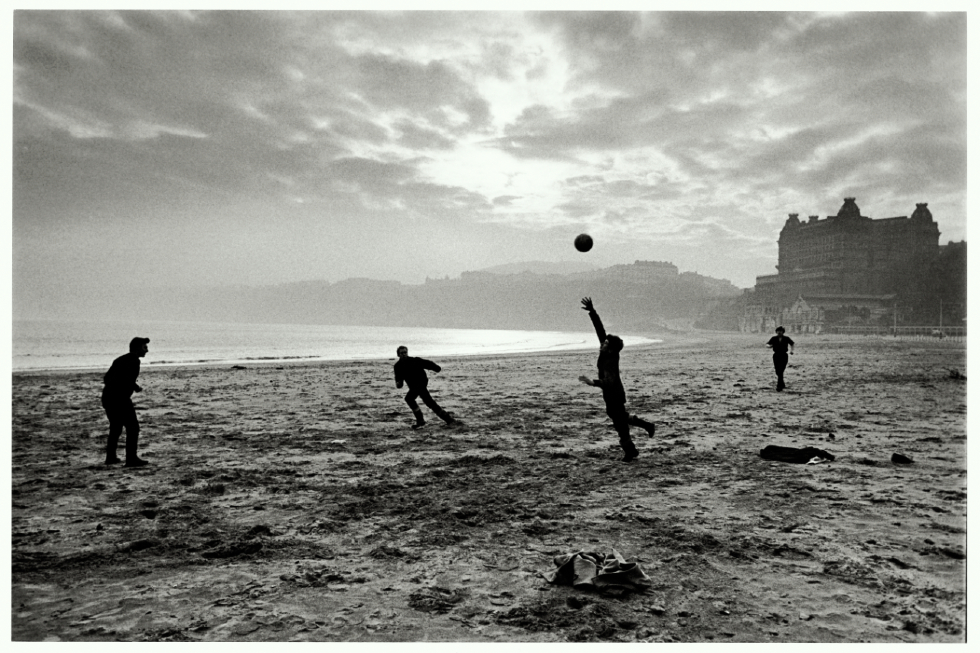

There is something of the sublime about the black and white photograph mounted with little fanfare against the grey gallery wall. It’s there in the glorious skyline: those gathering clouds, the mist of the seashore obscuring the coastline, which disappears into the distance on the left-hand side and, especially, in the bleed-through of the sun overhead. And although its author Don McCullin asserts that “I’ve never seen photography as an art form”, to me, there is more at play in this image than the timing, patience and process required to capture it. In addition to the elemental majesties above, in the medium ground are the fishermen of the title (who may as well be boys, with their jumpers strewn in the sand, for goalposts), having a kickabout during their lunch break on Scarborough beach. Its composition achieves an almost ineffable quality.

Juxtaposed with any number of hard-hitting images in McCullin’s back catalogue, it makes for the most naïve of scenes – one of humans at play in their downtime. Unaware of or untroubled by the photographer’s gaze, the men are lost amid the humble mysteries of what makes the beautiful game, well, beautiful. There is a suspension of life’s worries; no concerns about today’s catch, or about conditions at sea – the differences between putting food on the table and an empty stomach, or life and death; as philosopher Simon Critchley puts it, “football’s magic wards off oblivion”. Just as pertinently, Critchley also says that “Football gives us privileged access to abiding insights into what it means to be a human being in the world.” It is a position that recalls the oft-repeated Camus quotation: “All that I know most surely about morality and obligations, I owe to football.”

Perhaps such thoughts occurred to McCullin as he lined up and steadied himself for the picture. He is, after all, a man who has surely spent a career weighing his own morality and obligations as a photojournalist against what it means to be a human being in the world. Across more than sixty years, he has been a witness to war, social decay, poverty, and famine. Taken in 1967, Fishermen playing during their lunch break seems almost out of place, punctuating, as it does, assignments documenting humanitarian crises in Bihar, northern India, and in the Democratic Republic of the Congo; a civil war in Nigeria; and the Tet offensive, which weakened U.S. public support for the war in Vietnam. Could it have felt to him, as it does for us in the retrospective of his work currently on display at Tate Liverpool, like a golden moment of respite, a reprieve from the horrors that humankind can visit upon itself?

What does it mean to be the more-or-less passive onlooker to such things, hastily bussed in and out of warzones and other locations of calamity? McCullin has spoken about his having “a powerful ability to communicate” the hard truths – putting pictures, via the newspapers for whom he worked, in front of those who, one hopes, could affect positive change. As Susan Sontag has written in her essays on photography, there are two sides to this question – especially in the context of war. “When there are photographs, a war becomes ‘real,’” she has said. “Thus, the protest against the Vietnam War was mobilized by images.”

Indeed, McCullin’s photojournalism has often acted as a call to action both at home and abroad (ably demonstrated in the exhibition by a vitrine full of magazines carrying his work). But, continues Sontag, “in a world saturated, even hypersaturated, with images, those which should matter to us have a diminishing effect: we become callous. In the end, such images make us a little less able to feel, to have our conscience pricked”. And, certainly, McCullin has conceded to what he calls “a sense of your own powerlessness”. Many images in the Tate Liverpool exhibition attest to this position.

Fishermen playing during their lunch break stands out among these indelible images on display because it is one of very few that proffers a picture of humanity completely free of the pressures of responsibility – to anyone, whether they be in front of or behind the camera. All there is at stake is a ‘last goal wins’ scenario before getting back to work. And, I think, because it is the only image here – save for the beautiful shared look between a cat and a young boy (also taken on home soil) – that captures something of our innate joy, lost in the possibilities of things, while the maelstrom of life continues to swirl around us, unabated.

Mike Pinnington

Image: Don McCullin, Fishermen playing during their lunch break, Scarborough, Yorkshire 1967 © Don McCullin

See Don McCullin at Tate Liverpool until 9 May, 2021 – £13/Concessions

Read The Big Interview: Don McCullin