“Art is an integral part of a contemporary tourist offer”

Blackpool – Anything but Monocultural

Who does art serve and how, and does it depend on place? Mike Pinnington speaks to the curators at Blackpool’s Grundy Gallery to get a picture of how the seaside town is anything but “monocultural” …

Lately, I’ve found myself mulling over who and what art is for. Such questions are fundamental and so common place as to have become clichéd. We all think we know the answers, but it’s important to shake them off occasionally, to dust them down and reconsider them. Responses vary depending on who you speak to; geography and background (among other things) playing a role. Uppermost in formulating any answer, though, is the visitor. If you’re a big metropolitan art gallery with an almost Reithian sense of responsibility to ‘the audience’, for instance, then you have always to begin with an attempt (vane as it may be) to satisfy all – the local, the tourist, the first-time visitor, art students, the aficionado… the list goes on.

What if you’re almost at the polar opposite of this scale, though, operating in an old resort town in the north of England? How does that affect your thinking on who and what art is for? This is a question I put to Paulette Terry Brien, Curator of the Grundy Art Gallery in Blackpool. But, first, some context. The council-run gallery was founded in 1911 by the Grundy brothers with, according to its website, ‘the ambition to show the best art of the day to the people of Blackpool’. “They set up the gallery as a place for the people of Blackpool,” confirms Terry Brien, speaking with me over the phone. “[There’s] that sense that it’s for the town, of the town, but it’s also for visitors to the town.” As Terry Brien points out, industrialisation and the railways had made this a plausible ambition; “so the Grundy was being built as part of that boom of the entertainment industry, about attracting people from further afield to come to its doors.”

And, she says, that benevolence to its local populace remains a factor: “I think a lot about that actually, the role of the gallery in relation to that historical narrative.” Today, its founding principles are hand-in-glove with the ambition to exhibit international contemporary art. But the Grundy also exists as a kind of anchor institution for the visual arts in Blackpool as a whole – a town, given its size, not lacking in galleries and museums. In addition to the Grundy, there is LeftCoast, a commissioning body that works with residents, partners and visitors to produce work that plays ‘with those fair / unfair perceptions of “place” from different perspectives’. Then you have the artist-led, most visibly and coherently represented by spaces such as Abingdon Studios, established in 2014 by artist Garth Gratrix (a recent exhibiting artist at the Grundy). I wonder, given its scale, where everything fits amid the different relationships. I ask Terry Brien about how it works here, relative to nearby cities such as Liverpool, Manchester and Salford, where she had worked previously as director of exhibition and project space, The International 3.

“For me it’s interesting,” she says. “Being in Manchester for 25 years, and it always being about networking and sharing resources and a collaborative energy, for a ‘greater good’ as it were. I do feel, that even though it is on a much smaller scale, that is what happens in Blackpool.” Also operating in the closely-packed eco system until very recently, was another artist-led platform, Supercollider. Currently on hiatus, it was founded by Tom Ireland, who shares curatorial responsibilities at the Grundy with Terry Brien. A Blackpool native, he says the town “continues to amaze and provide a rich palette for artists to work from.” While the gallery “continues to move forward and grow under Paulette,” younger spaces like Abingdon Studios (of which he is co-director) “support artists in making, showing, and seeing new work.” It feels very complementary, I venture, a suggestion Terry Brien confirms: “the audience base is so diverse, and the practitioner base is so diverse. You don’t want lots of people doing the same thing, you want people doing a different thing so that there’s greater opportunity and a broader spectrum of resource.”

Of course, that broader spectrum of resource hopefully translates into a similarly broad spectrum of opportunity for audiences. Such factors are crucial to the make-up of a healthy creative landscape but Blackpool, as you may well be thinking, remains better known (comparatively, at least) for its entertainment heritage, something Terry Brien is keenly aware of. “I often hear people say ‘oh, you don’t think of Blackpool and culture.’” I can practically hear the exasperation in her voice. “But that’s quite an interesting statement, I think, because there is a culture here, built around the entertainment industry and the pleasure beach and the grand theatre, and that is a culture as well as contemporary art culture, that the organisations are involved in.”

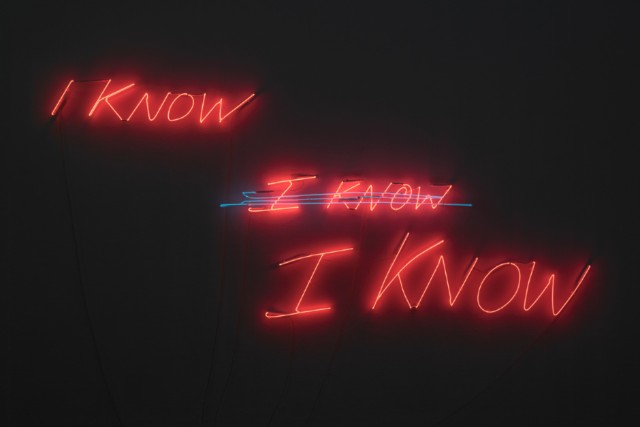

It’s not all Madame Tussauds and the Pleasure Beach. As Ireland points out: “tourists need things to do, see and experience.” And, indeed, the Grundy has never shied away from the town’s pop culture heritage. Consider the successful parallel 2016 shows NEON: The Charged Line, featuring work by Tracey Emin, Tim Etchells, and Gavin Turk, and the Illuminations Archive Exhibition, highlighting Blackpool’s pioneering role in Britain’s neon history. Such exhibitions demonstrate how you can embrace popular perceptions while introducing audiences to challenging, contemporary art.

One of the latest additions to the offer in Blackpool, Art B&B occupies space in both the contemporary visual art and tourism camps. While it is called a B&B, rightly or wrongly tapping into the wider public consciousness of place, the reality is more of a curated, boutique hotel experience, with each of its bespoke rooms made by contemporary artists. “I think that Art B&B is an interesting approach to addressing the middle ground,” says Ireland. “The broader, more interesting conversation, of which Art B&B is a part of,” he continues, “is to look at how art and culture is packaged and marketed to tourists visiting Blackpool. Art is an integral part of a contemporary tourist offer rather than an alternative to it; the cultural offer and the tourist offer are two sides of the same coin – cultural tourism is a key facet of the wider tourist economy.” Due to arrive next year and very much at the entertainment end of that economy, is Showtown, a ‘hybrid between museum and visitor attraction’ so says the blurb, that promises to put Blackpool’s heritage centre-stage. Its addition “to the cultural/tourism landscape will be an important moment,” says Ireland, who sees its potential “to elevate the cultural offer through the addition of a ‘signature’ cultural attraction.”

With those incoming visitors in mind, I’m interested in how the Grundy balances its responsibility to the audience on its doorstep with the tourists who continue to flock to Blackpool in their droves. Terry Brien tells me “There’s an audience that comes to us that is very show specific – which is the same as anywhere; they’ve come for that particular exhibition,” she says. “And then there’s an audience, a Grundy audience, that comes to most things that we do. [Then] you’ve got the fact that we are in a town that has a seasonal infrastructure.” That manifests itself in a “very clear and obvious movement between audiences – that sense that in the winter, it is very much the audiences are drawn from the local population, and then in the summer it’s a much broader spread of people coming to Blackpool for their holidays.” This changes again in the autumn, with the town’s famous illuminations, all of which, says Terry Brien, makes for “a very interesting dynamic: that sense of the local, the regional, the national and the international.”

That latter point particularly is one of the things that most interests me about the Grundy, especially in regard to its collection (which includes the likes of Anna Airy, Augustus Edwin John, and Gilbert and George), displayed alongside shorter-term, contemporary exhibitions. Where does that collection – begun with a bequest in 1908 – fit, and how do you employ it, I asked: “You can see this really diverse collection of oil paintings that go from the 1600s through to contemporary painters like Louise Giovanelli, that we’ve acquired in the last few years,” she tells me. “So, the collection, for me, that’s a very exciting thing… I’ve not had access to [one] before as a curator.” What’s important, and where the collection really does its job, she says, “is showing the works in their own right, but also [using them] as a resource to help bridge people’s understanding between what would be perceived as more ‘traditional’ art and the more contemporary art that some audiences might find challenging.”

Viewing the collection as a conduit for people to make the leap between what they think they know and what they don’t, Terry Brien makes the point that “historical painters [that audiences] recognise, were the boundary breakers of their time, just as [contemporary] artists are now,” before asserting: “I think that’s always quite a leveller. People have always been breaking the boundaries of their art forms across history.” Speaking about art’s potential and meaning to the audience, brings me back around to the related enquiry of who and what art is for. “That’s one of those massive questions!” laughs Terry Brien. “It’s one of the most fundamental questions that you just carry the answers around with you all the time. When you try to articulate it, you come out with all these clichés, but that’s the truth of it really.”

Does place and regionality play a role, I ask. Yes and no comes the nuanced answer: “For me, the arts, in Blackpool, it’s very much about – as it would be anywhere – helping people understand who they are, the times they are living in,” she begins. “What you have with Blackpool, you have that opportunity to tell people about the history and the present of the role of their town in entertainment, in tourism. But, for me, it’s very much about opening up a conversation as it always has been.” It’s an opinion echoed by Ireland, when he says: “Blackpool is an amazing place with a rich, unique, and complex history. It has amazing built heritage and stories to tell but it is often misinterpreted as a monocultural space. Art is a great vehicle by which to share those stories and should be given top billing.”

Mike Pinnington

Images, from top: Paulette Terry Brien; I know, I know, I know (2002). Tracey Emin. Courtesy the Artist. NEON The Charged Line (Installation View). Photo Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool; Shy Girl (2020). Garth Gratrix (Installation View). Photo Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool

This article is part of the series, ‘New Critical Writing North West: Voices on Lancashire & Cumbria’: new pieces of critical writing which will review and examine issues relating to the contemporary visual arts in Lancashire and Cumbria. The series has been commissioned by Contemporary Visual Arts Network North-by-NorthWest (CVAN NbyNW), and a new feature will be profiled on The Double Negative each month until October 2020.