Photographs from Another Place: In search of Sydney J. Gearing

When an artist purchased some century-old glass negatives online, he couldn’t have imagined the journey they would take him on. Mike Pinnington investigates the haunting of Alan J. Ward…

“I confess that I am often lost in all the dimensions of time, that the past sometimes feels nearer than the present.” – Deborah Levy, Hot Milk

Photographs, we know, are a fast lane to the past: personal and shared, and everything in between. They can be both intimate and culturally significant, sometimes becoming part of the global consciousness (as in those of Henri Cartier-Bresson, Dorothea Lange, or the iconic Earthrise). From the beginnings of the technology in 19th Century France (where the first photograph was made by inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, in 1826), to today’s proliferation of images, spreading like wildfire on social media, they tell the story of who and what came before.

Whatever the possibilities wielded by photographs – be it on a macro or micro level – we tend always to think of our relationship to them in the past-tense. Old family photo albums tell of a time before us; nervy first day of school poses remind us of our selves as bundles of pent-up potential, waiting to be unleashed on the world. We think of this exchange as one way; it seems, necessarily, intuitively, backwards-looking.

When we go through our old photos, then, it is usually for nostalgia’s sake; an aide-memoire. By extension, when we think of the term ‘sepia-toned’, it is almost always related not only to old, faded photos, but inextricably, to old memories, too; our mind’s eye conjuring the same sun- and time-bleached effect. You can see this desire to reconnect with yesteryear extend out into wider contemporary culture; in the resurgence of such recently anachronistic brands as Polaroid; in the lament at the passing of Kodachrome film, discontinued earlier this century; and in the use of Super-8 by filmmakers. Such fetishization of old formats lends a kind of faux-vintage, retro-cool veneer to present-day proceedings, all of which springs from and is based in a collective cultural nostalgia.

But the past isn’t necessarily inert; nor is it a cul-de-sac. Its tendrils have a way of creeping into ‘now’. Should we let it, it will insinuate itself in ways we could not have imagined. Once the door has been opened to the past, we are presented with certain questions. Among them: what if old photographs could impact our present, affecting the paths our lives are about to take? That is, having a say in our future. It might sound strange, fanciful even, but this is a question pertinent to artist Alan J. Ward.

In 2014, Manchester-based Ward, almost on a whim, purchased from eBay a collection of more than 230 glass negatives dating from c.1914 to the mid-20th Century. They “came in their original boxes,” he has said, “some of which were titled Wellington & Ward, the simple coincidence in surname gave them a personal value.” As he began to look more closely at their provenance, Ward – or, more accurately, his findings – set in motion a chain of events almost too numerous to think of as mere coincidence.

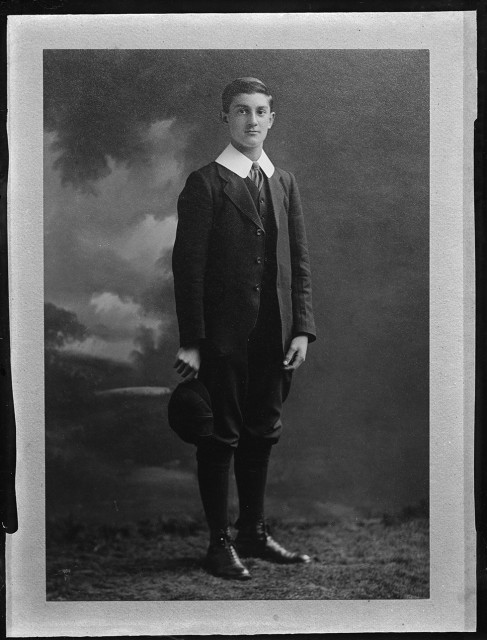

He became gripped by a past made physical by this set of negatives that he now thought himself custodian of. The majority of the photographs were made by Sydney J. Gearing (above) and, as Ward dug more deeply into the stories of the images and the people who appeared in them, he “pieced together the beginnings of a substantial family history”. In doing so, he found it shared echoes with his own. Most obviously, there were geographical correspondences; the families – separated by decades – having common migratory links, between Norfolk, London and the north-west. As Ward has said, acquiring the collection seems to have been pre-destined: “As I began to properly research the photographs… some very particular synergies with my own familial history began to form”. Such parallels, what he calls commonalities of experience, Ward has observed, “began to create some rules of engagement” for a wider project.

When we met just prior to lockdown, in March, he confessed to still feeling “haunted” by the photographs in some respects. And, as you find out more about the people who feature in them, they do take on greater texture; you can’t help but feel certain resonances emanating from the images, visitations, if you will. Certainly, there are ghosts here, but life, too. After undertaking what he describes as forensic research stemming from the photographs, he (along with anthropologist daughter, Bethan) constructed a Gearing family tree, from which he discovered that Sydney’s own daughter Ruth (below) was still alive. After tentatively making contact, he visited Ruth in Devon, and learned, amongst other things, that she still had her father Sydney’s camera. By now, Ward has said he felt like “Sydney was consciously engaging me” – little wonder; surely this was one such example, and Ruth subsequently gifted him the camera.

Rather than make it a totem or mere artefact of the past, gathering dust on a shelf, Ward decided he would put the camera to work. Making the short trip over from his home in Manchester to the Wirral, he visited some of the places and groups of people with connections to the stories he had discovered in the original photographs. There, he was able to identify locations that had been shot by Sydney, or were known to the Gearing family.

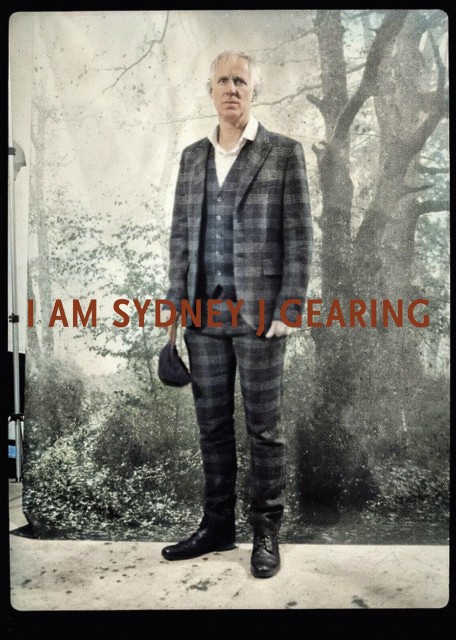

These included Parkfield Liscard Cricket Club (top), nee St. John’s (Egremont) Cricket Club, for whom Sydney had played; Grange Rifle and Pistol Club in West Kirby, who had competed against the disbanded Wallasey Rifle Club, where Sydney was a member in the 1920s and 30s; and what used to be Priestley and Sons Photographic Studios, in Wallasey (now a care home). There, he completed the circle, making a self-portrait in the guise of ‘Sydney’ (who had had his 1914 graduation picture taken there).

The past, now fully making its presence felt, was butting up against the present in very real terms. It was seemingly guiding Ward’s hand as he made new work, portraits that captured a shared cultural heritage from then – 1914 – to now. The logical next step was to put the two in direct conversation, introducing yet another layer to the Gearing/Ward annals. The resulting contemporary photographs, just months later, were displayed alongside a selection of the originals in Photographs from Another Place (below), an exhibition at Birkenhead’s Williamson Art Gallery (a museum Gearing himself visited).

If the past really is a foreign country, then we have more in common than that – in this case, the years – which divides us. I began by posing a question about how old photographs might influence our present. I’ll end with another, just as relevant to Gearing and Ward, and it is this: given everything, who’s haunting who?

Mike Pinnington

Photographs from Another Place is touring to Norwich Cathedral September–October 2021. The Williamson Art Gallery exhibition is fully documented on the artist’s website.

The book of the project is available at Dewi Lewis Publishing or directly from the artist where a limited number of signed and numbered copies of the book are available at a special bundle price during COVID-19