Insane Energy: Lifting the Lid on Kötting and Kubrick

Boxes and their contents – figurative and otherwise – loom large in both Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and Andrew Kötting’s The Whalebone Box, finds Lee Ashworth…

Open the box! Open the box!

Open the goddamn box!

– The Fall, Open the Boxoctosis #2

It may seem jarring to invoke the glacially cool spirit of Stanley Kubrick when considering the impact of such a lo-fi film as Andrew Kötting’s The Whalebone Box, but containers and their power in both form and content, figure prominently in the work of both directors. Boxes and their potency reveal a lot about their attitudes – not only towards film but perhaps towards life, too. What does our appreciation of these films reveal about us and our sense of meaning in the world?

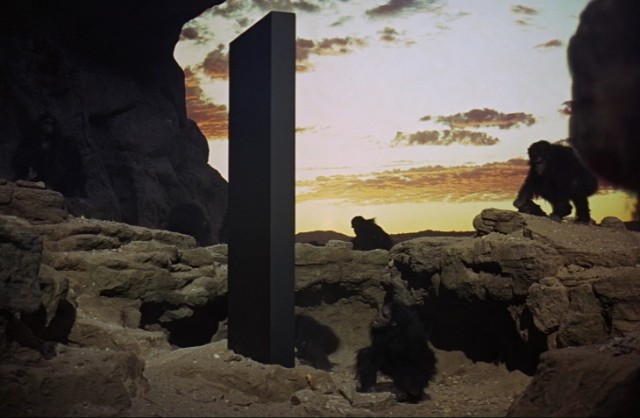

The preoccupation with the titular box of Kötting’s recently released movie, its cryptic quality, ruminations on its mysterious contents and discussions about its potential to release ‘insane energy’, resonates with the recurring image of the monolith in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Shorthand for something ominously portentous, it has become a meme widely recognised as a cultural signifier beyond the film’s primary audience, insofar as it is now buried deep in our collective consciousness. Arguably, the salient though ambiguous significance to its inclusion in 2001, is that the monolith has always been there, albeit in our collective unconscious.

In the film we see that it was present at the crucial moment of evolution between more primitive apes and homo sapiens, at the dawn of the use of tools and the expansion of consciousness that ensued. We see it awaiting human discovery on the moon and finally, a monolith appears before the astronaut Dr Dave Bowman at the end of the psychedelic star-gate, as he perceives himself through the ages of his own life-span before and after that moment.

Kubrick presented the monolith, quite literally, as a touchstone capable of affecting, or at least signifying, evolutionary changes and perhaps, more specifically, changes to our understanding as humans (and arguably, pre and post humans). Part of the enduring legacy of 2001: A Space Odyssey is that its appeal lies beyond the realm of genre-based sci-fi for it is an existentialist meditation – in its purest sense it asks us what it means to exist. Is there a grand narrative within which we play a part?

The use of music in the film is key. Renowned (or perhaps, more correctly, infamous) for his indefatigable attention to detail, Kubrick’s later films are often regarded as having nothing that is not significant to the plot. This extreme interpretation of Chekhov’s Gun, i.e. the maxim that every element of a drama must be significant to the plot, has given rise to many conspiracy theories – yet in 2001, the music resonates with this theme of evolutionary change. The eventual choice of a pre-existing classical score rather than original music represents a sonic articulation of the significance of the black box monoliths.

Mystery contrasting with a climactic sense of impending revelation abounds in Ligeti’s Atmospheres and the Requiem, whereas it is almost impossible to separate 2001 from Richard Strauss’ Also Spake Zarathustra. But note the title of the latter, from a philosophical treatise by Friedrich Nietzsche, a fragmentary account during his late period, expounding his thoughts on man as a ‘tightrope’ between ape and übermensch. The black box monoliths of 2001 frame just such a narrative of humanity, abstracted and encapsulated as a synecdoche through the overview of Bowman’s individual lifespan: the personal enveloped within the far wider scope of a grand metaphysical system. In one sense, human existence, as a project, is the contents of Kubrick’s boxes and during the film it is unpacked before our eyes – albeit with much to interpret.

Beyond his films, Kubrick bestowed another legacy in the form of an intimidating number of boxes that now constitute his personal archive of memorabilia spanning a lifetime of filmmaking (Stanley Kubrick’s Boxes, 2008). For Kubrick, in filmmaking life and death, boxes are repositories for the constituent parts of things. On screen, he unpacked and directed the assemblage of those parts, piecing together jigsaws with iconic and revelatory images musing on sex, war, violence, and the meaning of life. His humble cardboard boxes are now plundered for revelations about his working methods, as though we could disgorge the photographs of endless front doors he amassed whilst researching his final movie, lay them all out before us and behold the constellation of his creative mind.

Just as between Bowman’s star-child foetus and his dying, bed-ridden body, there is the mundanity of a life punctuated with exceptional events; once the contents are removed from the boxes of Kubrick’s repository there are just sets of photographs ordered by someone whose exactitude in his craft led to a great deal of artistic and commercial success. Kubrick’s boxes, on and off screen, real and metaphorical, are mysterious and revelatory, looming large in the myth of Kubrick The Artist. Their contents are the everyday, the commonplace, the laborious, the rigorous, even the wonderment and catastrophe that can befall conventional lives.

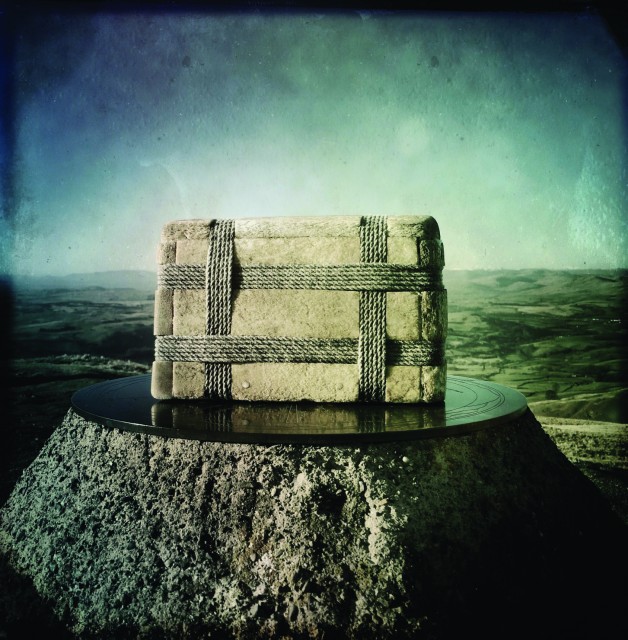

In a recent interview with Antonia Quirke for BBCR4’s The Film Programme, Andrew Kötting described his own medium as ‘shoddy films’. In contrast to the recent Ultra HD 4K version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kötting’s latest ‘shoddy’ film, The Whalebone Box, eschews conventional expectations around industry standards for resolution. Instead, Super 8 footage, pinhole photography and archive clips are blended into a dreamlike montage, presenting a unique, unclassifiable combination of travelogue, documentary, art and philosophy. Ostensibly, the film chronicles a pilgrimage from the London home of the psycho-geographer Iain Sinclair to restore The Whalebone Box of the title to its place of origin on the Isle of Harris.

The box is at the forefront of the film, physically present in many of the scenes. It is also at its heart. It leads the narrative, yet it is arguable whether there is any narrative at all in a conventional sense, beyond the bones of the premise. The box, the narrative and the film itself are all conundrums entwined within this strange, at times beautiful but also unsettling meditation… on what? Implicitly, within the premise of the pilgrimage and explicitly through the words of the narrators, the question of what is in the box is the film’s driver and, also, its subject. The box is a MacGuffin of sorts: a genuine artefact whose gravity also bends the shape and space of the narrative – such as it is.

At the outset of this unconventional and impressionistic film, we are told that the titular box was created thirty years ago by Hebridean sculptor Steve Dilworth, who creates a ‘cosmology’ of totemic sculptures from the juxtaposition, fusion and transformation of natural artefacts acquired in the relative isolation of Harris:

“Two birds, beaks crossed, found dead in the nest. The sun-dried carcass, mummified, skin shrunken around an armature of bones. A cat and a rat, reanimated in frozen dialogue. The armadillo’s armour, sparrow hawk’s talon, the earth, braided grass and rope, carapace, coffin, the vast geology of indifference, collected and re-built, reimagined as totemic coordinates. The skull and stones.”

Constructing the box from the washed-up bones of a whale and melted lead weights, Dilworth filled the vessel with ‘calm water’. Yet this raw information seems incidental to the significance and the meaning of the box, the procession of its entourage and this whole project. Sinclair muses on the prospect of unleashing the ‘insane energy’ of the box and refers to it as the ‘animal battery’ that has resided on his desk for three decades. Throughout the film there are references to the black boxes of aircraft and perhaps the pre-eminent box of contemporary cultural consciousness – that which contains Schrödinger’s cat.

“It is a bomb. A black box, the record of what went wrong. Pandora’s box, the hurt to be released. It is a coffin. A house, the place we build in place. It is a space. Held and holding. It is the purring of Schrödinger’s dead cat. The whale bone box is, without a doubt, a doubting, heavy, multitude.”

Ambivalence is writ large in such talk of containers and their indeterminate contents. It is easy to see the isle of Harris as a geographical extension of such metaphors: Schrödinger’s cat is a hypothetical construct, the Whalebone Box is a real artefact with indeterminate powers (suspending the truth of this for a moment) and Harris – although a real location – remains remote and mysterious to many. Taking my first trip to the Western Isles almost twenty years ago, I recall the sinister remnants of the former whaling station at Bunavoneader, featured in the film. Watching the archival footage of the whale being stripped in Kötting’s film recalled my own observations of the place itself with its concrete slipway jutting out of the loch like a tombstone.

The world was less connected then, and expanses of physical distance were easily amplified by such sights. Although the station was long abandoned and derelict, the endurance of its remains (now a monument), contributed to my impression of a place that straddled several centuries of history simultaneously. A place, from my naive tourist’s perspective at least, of indeterminacy. In my memory this was compounded by an exploration that same overcast day, of a decommissioned military base that had been unsuccessfully converted into a short-lived holiday camp, though after consulting guide books and searching the Internet I can now find no evidence that any such base existed, leading me to question the veracity of my own memory. There is something enigmatic if not cryptic about the Isle of Harris: it is the perfect location for the culmination of Kötting’s progress.

The enigmatic is pursued through the presentation of whale song intermittently throughout the film as performed by Scots poet-singer MacGillivray to great effect. We hear the song, succumb to its beauty and its sadness but its meaning is ultimately elusive. Andrew Kötting’s daughter Eden is a central and enigmatic figure throughout, narrating aspects of the journey, her spoken words accompanying the juxtaposition of images that create a cinematic and auditory analogue of Dilworth’s totemic cosmology. In the ultimate extension of the inquiry of what is in the box, Andrew appears to be inviting us to speculate on the minds of others as we watch Eden sleeping – what is she thinking, feeling and perceiving?

And what is the answer to that? What is Kötting’s answer in The Whalebone Box? The box, the film and possibly Kötting’s wider artistic project, all serve to deepen the mystery of existence rather than resolve it. In contrast to Kubrick’s boxes, when we strip Kötting’s work down to its raw constituents it is always more than the sum of its parts – there is an excess: something mysterious and unaccountable that enhances rather than seeks to explain away the vitality of life. It is the rejection of binary modes of inquiry such as simple questions and answers, black or white, problem and resolution. It is the acceptance of a plurality of meanings. It is an affirmation of the kind of ambivalence that Schrödinger’s cat invites us to acknowledge – it is a multiplicity rather than a reduction.

Through this pilgrimage and the artefact of indeterminate power at the centre of it, Kötting champions what it is like to be alive. While there is an unfortunate irony in the release of a road-movie of sorts at a time of isolation, The Whalebone Box may resonate most with those of us searching for a greater sense of meaning at this time when our days are dogged with questions about the more immediate practicalities of life, the answers to which are not forthcoming. Andrew Kötting and his titular box exhort us to live: to simply be, amongst the mad riddle of it all.

Lee Ashworth

The Whalebone Box is available to stream now on Mubi; Watch 2001: A Space Odyssey on BFI Player