The Lighthouse and Bait: Striving for Authenticity in Narrative Cinema

“There is tension between the real and the virtual, the authentic and the simulated.” Lee Ashworth searches for the authentic in the choppy waters of narrative cinema…

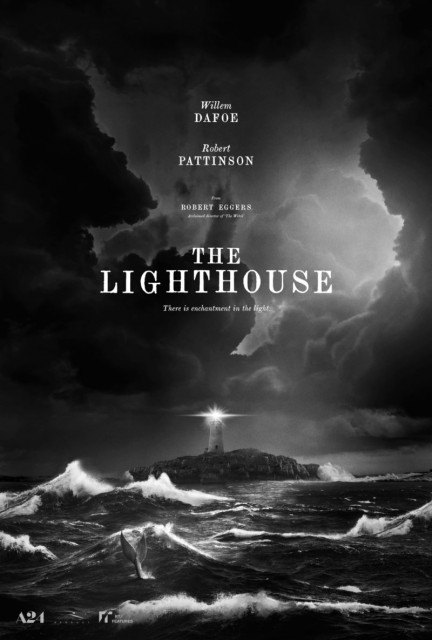

The Lighthouse (2019) is one of the most singular and strangely compelling films of recent times. Like a salty and sodden cinematic black hole, it appeared to exert a distorting effect on reality either side of the screening I attended: the roads into the city were slick with the standing water of Storm Ciara and we sat eating lunch with buckets behind us, carefully placed to catch the rain leaking in from the restaurant roof. After the wave-lashed reverie of the film itself, we journeyed home through thunder, lightning and hail. The idea of this as ‘the complete cinematic experience’ wasn’t lost on me, yet in truth any suggestion that specific conditions should be required for one to become fully invested in director Robert Eggers’ second feature is to detract from the truly immersive experience that it is.

While The Lighthouse cannot be said to command its own weather system, it is well documented that Eggers, his cast and crew, went to extreme lengths to create a work of authenticity. Filmed on the coast of Nova Scotia in challenging conditions, cinematographer Jarin Blaschke shot in orthochromatic 35mm film, offering a cold harsh palette. There are also stories, possibly apocryphal, of co-lead Robert Pattinson being pushed beyond his limits just like his lighthouse-keeper assistant, known as a ‘wickie apprentice’, Winslow in the movie.

Aside from the practical craft of the film, Eggers has a reputation for insatiable and obsessive research. In addition to a rich yet obscure cinematic heritage, literature both ancient and modern was pored over, from chronicles of coastal lives to Edgar Allan Poe and beyond. The cumulative effect is a film steeped in a potent brine of symbolism and language that allows for a most intoxicating expression of the struggle between two men wedded together as barnacle and rock. Visually, the viewer is presented with the arcane mysteries of scrimshaw and specific types of mermaid, whereas aurally, incredible attention has been paid to lexicon, register, dialect and accent – redolent of an ideal of seafaring lingo rather than regional or historical precision.

Directed by Robert, The Lighthouse was co-written with his brother Max (whose original idea the film was adapted from). And it is clear that the brothers Eggers have undeniably done their homework; it is to the credit of the film that nothing feels excessive or heavy-handed, rather, a convincingly holistic world has been created. In many ways, the key parallel here is with the mother of all seafaring tales that is Melville’s Moby Dick. Both works use various forms of mythology as framing devices, from the Biblical references and influence of Homer’s Odyssey to name but two in Moby Dick, to the homage to the fate of the fire-stealing Prometheus in The Lighthouse.

The Lighthouse is suffused with symbolism in almost every frame, while form and content appear to be conceived in pursuit of esoteric detail. Is this rigour borne of an anxiety in Eggers’ mind that, without shoring up the film in this way, suspension of disbelief will not be achieved? Start looking up relatively minor aspects such as the scrimshaw (or Melville’s “skrimshaw”) and the multiple layers of meaning and significance are dizzying: the film, like Moby Dick, appears to be a window onto a fully formed, self-contained world. Yet, of course, most people would no more pursue such things than they would actively search for continuity errors in a movie. In these ‘post-truth’ days, where fake news is at large and the advice of ‘experts’ is often disdained by political leaders, an emphasis on verisimilitude – authenticity – in a film that has garnered critical praise and a relatively wide audience is striking.

Our times can seem maddeningly ambivalent: the question ‘don’t we believe in anything?’ embodying such a feeling. The phrase, largely rhetorical, bemoans a lack of conviction. In trying to steer towards authenticity, Eggers attempts to navigate a channel between those jagged rocks that flank us on either side. The success of The Lighthouse, critically and financially, suggests that a fair few of us are on board too, teetering in the westerly, trying to find our feet and hold our balance between the extremes.

As challenging as it sometimes is to gain distance and perspective these days, the aspirations towards authenticity in The Lighthouse resonate in a world that is becoming increasingly virtual. As our lives become less real, perhaps we look towards art to compensate and become more tangible somehow. But as soon as we admit this possibility, we find the spectre of Baudrillard’s Simulacra engulfing everything, for even the most authentic expression of art is still a simulation of the real.

This tension – between the real and the virtual, the authentic and the simulated – may be a subtext entwined within the production of The Lighthouse, but it is the key theme at the forefront of the recent, similarly successful Bait (2019). Set in a contemporary Cornish fishing village, the residents are haunted by traditions of the past and uneasy about a future in which roles and identity shift like the harbour sands beneath their feet. As with The Lighthouse, Bait was shot using antiquated equipment – in this case a hand-cranked Bolex H16 camera, on 16mm monochrome film hand processed by director Mark Jenkin.

With stuttering imperfections reminiscent of early silent-era cinema, every taut fibre of tension in this post-industrial stand-off is revealed in the abrasive grain of the film’s aesthetic. The plot focuses on the effects of gentrification in an erstwhile fishing community where the traditional, authentic way of life, i.e. the fishing industry, has been usurped and transformed in every respect. The boats that used to go out fishing now host pleasure cruises and the skipper’s cottage has become a holiday home replete with maritime-themed interiors. Rather than evolving into something else completely, the place has become a simulacrum of a fishing village. Such inauthenticity is writ large beyond the frames of the film. Walk through the hip areas of any major city and you will find beards, cable knit sweaters and cagoules: the quasi-utilitarian chic of post-industrial people the world over, wearing the clothes of those left behind.

Aspirations are key to understanding Bait and The Lighthouse. In the former, the village is a fractious battleground for those who wish to continue the old ways, those willing to diversify and the opportunists seizing what they can for themselves. In the latter, we find Pattinson’s Winslow clawing his way to the top of the spiral staircase to finally gain access to the light itself. Ruminating on aspirations at the outset of Moby Dick, Melville writes of trying to attain “the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all.” Eggers and Jenkin take every opportunity to anchor their movies in the depths, to shore up our footing, as we get ready to take a leap of faith and follow their characters’ ambitions. It resonates because upward mobility is ultimately thwarted and, perhaps, we too are stuck in a grand sense: here we are, marooned on our island, battening down the hatches in a vivid simulacrum of a past that is itself more myth than reality.

Lee Ashworth

The Lighthouse is still in cinemas; watch Bait on BFI Player

Images, from top: The Lighthouse (still); The Lighthouse poster; negatives from Bait; Homepage: Bolex/Bait © Thom Axon