Time & Space: On Being a Gallery Invigilator

“You are both a font and a target.” Stephen Curtis reflects on his time as a gallery assistant, which affords philosophical freedom while also making you a magnet for the pedantic, and those looking to lay blame for their confrontations with the esoteric…

The painter Robert Ryman looking back on his early development as an artist, once remarked “I would usually pick up jobs that left my mind free; working in a library or a museum as a guard were the kind of jobs that seemed ideal.”

Having worked as a museum guard (gallery assistant, visitor assistant) for some time I can corroborate the lack of take-home stress and philosophical freedom the post can offer and yet the mind of the museum guard is just as likely to stagnate as run clear as a mountain stream; you do time as the convicts say. The job seems ideal for the young art student, or the semi-retired. To the casual observer, the all-important visitor you are merely guarding, stretching or maybe staring into space; as with a coffee pot, all the percolation going on inside.

Randall Jarrell in his poem In Galleries has noted…

The lines and hollows of a piece of stone

Are human to people: their hearts go out to it.

But the guard has no-one to make him human –

They walk through him as if he were a reflection.

You are both a font and a target; complete strangers will deem you culpable for the taboo or the esoteric on display and in the same breath look to you for a guiding hand, directions for cabs and decent restaurants.

Peripheral vision soon sharpens up with experience and the reading of body language becomes second nature. You successfully match up couples and mark new trends; tattoos for example spread with meme-speed around the turn of the millennium, intricate designs more at home on Queequeg’s face now decorate the exposed flesh of public school and council estate alike. You complete circuits of a designated space for a pre-set time, make yourself available or keep a polite distance, all the time watching, invigilating. I’ve crossed rubber-tipped swords with scores of sceptics but there are of course heart-warming catch-ups to counterbalance such prickly encounters. Names escape and faces jump out from crowds. Focus expands and contracts by the hour; the brain constructs alternative futures and sifts through memories, ruminates over the art works adorning the walls and floors.

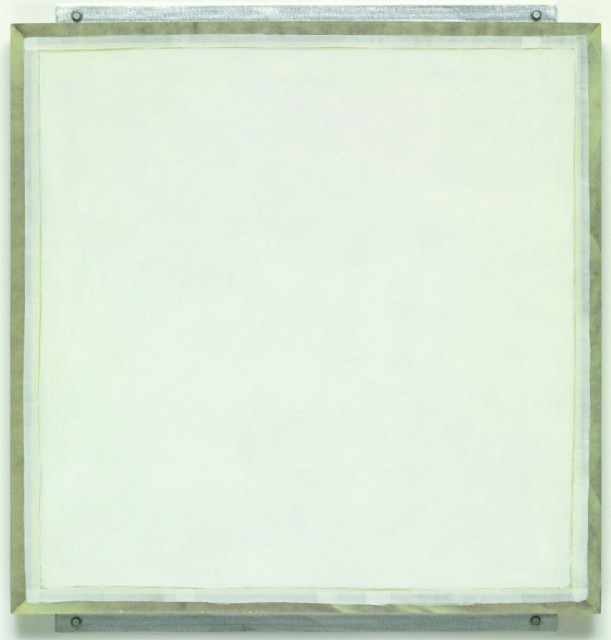

‘Graph Paper…’ was the opening gambit of one cynical visitor regarding a delicate line painting from 1965 by Agnes Martin. Many visitors demand some level of ‘skill’ or trickery in the art works on display. Op Art special ‘effects’ masters such as Bridget Riley and Jim Lambie score well whereas Robert Ryman and Agnes Martin are largely ignored or vilified outside of academia. Two white monochromes of Ryman’s (both 1982) were on display for a year or so at the gallery and I got to spend time with them most days.

Starting out Ryman was an aspiring jazz horn player and worked for seven years as a guard at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan. This formative experience elevated Henri Matisse and Paul Cézanne to the higher cultural plane previously reserved for the likes of Lester Young or Charlie Parker.

On discovering this I pictured the young budding painter patrolling the galleries, quietly composing, surrounded by colour and dreaming in whites. After his untitled (orange) painting of 1955 he reduced his palette to whites contrasted with creams, the pale browns and greys of different papers, hints of ochres glimpsed beneath a milky veil. Perhaps for Ryman, his paintings were (at least at the outset) on some level purgative, eschewing illusion or narrative, a whitewashing of history thereby enabling his own unique contribution to the great endgame of Modern Painting, that theoretical fight to the death over the square, canvas (or wood) as object, window onto the world or signifier; the playing out of five hundred years of crucifixions, kings, popes, fish and candles, cubes and cones, drips and slashes.

Or perhaps I was locked into my immediate environment in a way a hostage might end up appreciating the lines and hollows of a radiator if chained to it long enough? The composer Morton Feldman wrote of Ryman’s contemporaries Pierre Boulez and John Cage: “In the music of both men, things are exactly what they are – no more, no less [...] What is heard is indistinguishable from its process.” Robert Ryman’s paintings are very much process paintings, they are exactly what they are. There are always days when contrary questions need to be asked and on those days I could see Ryman’s endless deliberation over ‘what is to be done with paint’ and the substantial academic analysis of his practice as perhaps no more than the application of theory to an act not too dissimilar to a carpenter sourcing the right wood and fixtures, cutting and gluing a perfect chair.

A late realisation led me to believe that Ryman’s work can be turned both ways; the right materials combined with intellectual enquiry producing the satisfying form. The New York poet D. Nurkse could just as easily be referencing Ryman when observing in his poem Making Shelves…

I cut plexiglass on a table saw,

Coaxing the chalked taped pane

Into the absence of the blade,

Working to such fine tolerance

The kerf abolished the soft-lead line.

There are days when being a museum guard is easy, relaxed and full of sensual delights, yet an equal number when time leans on you like a loan shark. The longest stretch of your day falls at the close. Depending on different runs in the day sheet, on which space you were to patrol, this could prove breezy or a sentence served. I remember in one particular gallery some years ago concentration and reasonable conversation had been – for some time – severely hampered by Gary Webb’s Sound of the Blue Light, an installation playing and replaying a mix of Somewhere Over the Rainbow and Wonderful World sung by a Hawaiian ukulele player, recently deceased. A mobile phone advertisement had made his name, several visitors had informed me. One or two of my colleagues revealed a soft spot for the piece, but for the majority (including myself) the cyclical repetition of the songs burrowed into the brain with the determination of a jungle parasite and intermittently interfered with contemplation of anything else (including the two Ryman paintings) within the shared space.

One of the great mysteries of the contemporary art world is the frequent contempt shown for the ear and background sound’s ability to so radically alter (or cloud) the vision of the eye. I found it impossible at times to take in other nearby works without having images churned up of a young Judy Garland or the older Satchmo with his white handkerchief derailing my train of thought. Younger students however were not in the least put out by this I noticed and would keep one earphone in as they sketched and text and took pictures. Every seven minutes the loop would begin and I recalled news footage back in the 80s of the American 75th Rangers smoking out General Noriega. The Rangers sat outside the General’s compound blasting a play list featuring Guns & Roses, Black Sabbath, Funkadelic. Whilst the compilation was decent (though whether this was to the General’s taste we can only speculate) the round-the-clock repetition would have been the killer.

My heart went out to Noriega; in my time working the galleries artist’s employing a song or a phrase on a loop have not enamoured themselves to the guards, the visitor assistants – Mark Wallinger’s helium high Victorian dirge on infant mortality a contender for top spot. There have of course been notable exceptions to this form of aural torture; Douglas Gordon’s yellow vinyl room (representing the womb of the artist’s mother and the classic modern jazz such as Horace Silver’s Tokyo Blues he as a foetus may have absorbed) and Janet Cardiff and George Miller’s 40 Part Motet, an ingenious appropriation and fresh-take on Spem im Allium by the English composer Thomas Tallis (c.1505-1585) serving to remind the modern art pilgrim of the magic of the human voice.

For the recording, each member of the (Salisbury Cathedral) choir – men, women and children – had been miked up individually. For the discerning visitor the absent presence of each chorister is eerily embodied within a single speaker positioned at approximately the singer’s head height, enabling the listener to eaves drop in on the chitchat, the occasional laugh and even the breathing prior to the performance. Dozens of recordings of this (the most famous Tallis composition) exist yet no matter how many times the visitor may have heard (or perhaps even performed) the motet he or she cannot have experienced it quite like Cardiff and Miller have made possible, rendering the audience invisible, able to drift amongst the choristers with the anonymity of the angels in Wings of Desire keenly observing, listening in on what makes humans tick.

Stephen Curtis

Time & Space is the opening essay from the collection Freedom in Captivity: The Art of Being a Museum Guard, by Stephen Curtis. It is available to buy now from stockists including Open Eye Gallery, in Liverpool.

Images: Photograph © Roger Sinek; Robert Ryman, Ledger (1982) © Robert Ryman