A Waking Dream – Rebecca Allen’s The Observer

What’s a video-game without its heroes and villains, guns or explosions? Mike Pinnington investigates The Observer, Rebecca Allen’s ‘moving painting’, currently part of an exhibition at FACT Liverpool…

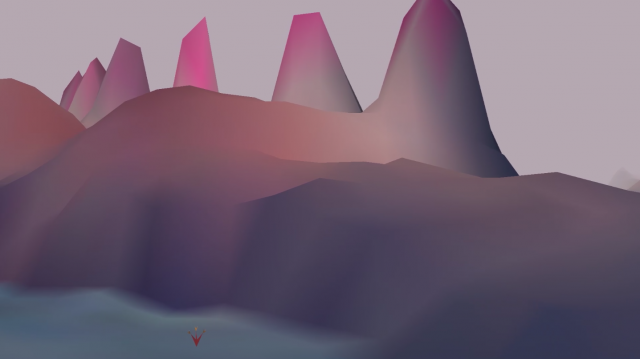

In both scale and depth, dominating FACT Liverpool’s current exhibition You Feel Me_. is American artist Rebecca Allen’s ‘moving painting’, The Observer (1999-2019). For those of a certain age, it is deeply evocative of turn of the century video-games. Despite this, however, there are no speeding vehicles, gunships flying overhead or lightsaber wielding protagonists or foes to be found in the work. Choosing to eschew the wall-to-wall violence central to many a gaming experience, with The Observer, Allen has crafted a vivid waking dream of another world.

Working in the field of digital art since the 1970s, and concerned with the aesthetics of motion, the study of perception and behaviour, she has said: “I’ve always wanted to make a moving painting using digital tools that really hadn’t been invented yet… I wanted to do something very different … so that the viewers could see a possibility of a world that has beauty and interesting forms.” But memories stimulated by my own nostalgia for that halcyon era of Sega, Nintendo and the first iterations of Sony’s then new kid on the block, the PlayStation, means that one can’t help but project certain scenarios onto the landscape. The expectations of hardened gamers, therefore, may be of a static, or boring, experience.

On the contrary. There is much to discover and absorb in The Observer’s cosily retro environments. Across the 60-minute running time, you can travel from the snowy wastes of one land mass – replete with polygonal mountainous terrain and its ice caps – to an expanse of arid desert. Strangely mesmeric, spaces ordinarily occupied but left open by Allen (no warring factions here), provide you with room for contemplation – and, a kind of meditation. With no goal, coins to collect or end of level boss to vanquish, once fully immersed, time takes on a non-linear quality. World building happens, but it does so in your mind as opposed to the experience of interactive gaming simulations. There are lifeforms of sorts here, too. As the digital painting moves and unfolds, revealing its different – and pretty simplistic by today’s standards – habitats, we encounter darting birds (which look like paper planes), spinning top vegetation, spurting geyser-like mounds, tentacled subterranean beasts and weird tripedal crustaceans – or are they living rock formations?

The point seems to be that they are whatever your perception tells you they are. The flora and fauna of this world, basically rendered though it is, invites reflection and consideration. Soon, lulled by the gyrating forms, your imagination takes hold, summoning more questions. Do the different species interact? If so, in what way? If you could climb into their world – be the alien – would you discover them to be self-aware? They are fascinatingly, almost uncannily, animate, wheeling across the screen with a bizarre, unknowable intent. This was achieved, Allen explains, “with a new area of science tied to artificial intelligence called artificial life, where we built a behaviour scripting system, [in which] you can create rules of behaviours for these abstract characters. I would just set them to life.”

Spend enough time in the painting and you’ll spy huge skeletal remains. Picked clean by carrion, the elements and time, judging by the lack of comparable animals moving around, they have, perhaps quite recently, been lost to the ages. There are signs, too, from what little infrastructure there is, of intelligent civilisation. Although any such life that had inhabited this world is nowhere to be seen. Where are they? What happened to them? Destroyed in a fit of their own hubris perhaps. In light of recent events, it makes for a chilling and scarily timely warning to humanity – that we’re too eager to put up walls, guzzle fossil fuels in the face of rapid climate change and haphazardly carry out state-sanctioned assassinations. Good art always has something to say about the world.

This alternative world Allen has created, is ripe for the imagination. Inspiring thoughts of what could be rather than what must or what is, here is the road less travelled – one that, once you’ve committed to it, is as liberating and filled with possibility as it is untrodden. The only limit is your imagination.

Mike Pinnington

You Feel Me_ continues @ FACT Liverpool until 23 February

Images: Rebecca Allen, The Observer (1999 – 2019). Installation view at FACT. Image by Rob Battersby; Stills of The Observer (1999-2019), Rebecca Allen, courtesy of the artist.