The Death of America: David Lynch’s My Head is Disconnected – Reviewed

David Lynch – the director of films exploring America’s dark underbelly – is revealed in exhibition, My Head Is Disconnected, to be equally adept at rendering that nation’s ills in paint, finds Lee Ashworth…

David Lynch – the director of films exploring America’s dark underbelly – is revealed in exhibition, My Head Is Disconnected, to be equally adept at rendering that nation’s ills in paint, finds Lee Ashworth…

My Head Is Disconnected is the first major UK exhibition of the artwork of David Lynch, currently on display at Home Manchester, programmed as part of this year’s Manchester International Festival. Curated by Sarah Perks and Omar Kholeif, eighty-eight of Lynch’s works are split into four thematic chapters: City On Fire, Nothing Here, Industrial Empire and Bedtime Stories. Like other artists who gain prominence in one medium, Lynch’s artwork is often regarded as an aside to his directing work. However, My Head Is Disconnected allows for immersion in the wider scope of Lynch’s aesthetic, informed by key themes that articulate the Death of America in which the vision of an idyllic, wholesome way of life is revealed to be but a thin veneer masking a darker urban reality in which personal identity is volatile.

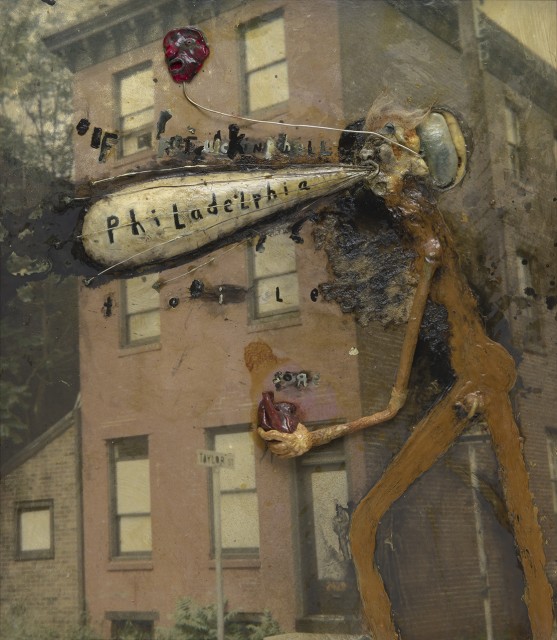

Situated discreetly in the Bedtime Stories chapter of the exhibition, Philadelphia (2017) is an incredibly striking work that lures one’s attention towards its dark provenance. Perhaps the most ostensibly autobiographical work on display, it articulates the time and place in Lynch’s life when the small town folksiness of Boise, Idaho morphed into a world mired in murders, riots and urban decay on his doorstep and inside his home. This was the moment when the lid was blown off and the true darkness – often referred to as the underside of modernity – began to reveal itself. The locus of Lynch’s creativity lies not in Philadelphia itself, but in the molten fault-line between those two worlds.

Here, an innocuous photograph of Lynch’s residence at the time is partially obscured by a naked giant stalking the foreground with its author’s own white wisps of hair, his heart in one hand amidst some sort of explosion, fusing the two aspects of the work together. While ‘mixed media’ may be a frustrating description in lieu of more precise information about the fascinating range of materials used, in terms of form Philadelphia is a synecdoche of everything that works well in this exhibition: scale, striking use of colour, layers and collage that create a highly textured work, stimulating to the senses yet repellent in content. This playful, perhaps indulgent use of materials – the thickness of the paint, the excess that prevails in the liberal use of other viscous media – is redolent of the ambivalence of late capitalism itself: the irresistible attraction of colour and textures proffered through contemporary consumerism and the repellent and disturbing stratum beneath.

The Bedtime Stories chapter resonates most, incorporating the aforementioned Philadelphia and the disturbing, floating worlds of Billy And His Friends Did Find Sally In The Tree (2018) and I Was A Teenage Insect (2018). This late period of Lynch’s art brings the grotesque to the fore through the depiction of traumatic events. Yet amongst these shocking scenes are some of the more readily identifiable motifs for which Lynch is known: picket fences, abstracted and degraded from his celebrated film Blue Velvet’s (1986) sparkling white, strike out against distressed plasterboard and stencils of detached houses abound. These icons of domesticity are synonymous with that small town, middle-class America whose security has been gradually eroded during the post-war years, and the imagery is echoed throughout his visual work including the lesser known 2008 short, Bug Crawls.

Within and between the chapters, we find repeated articulations of shifting identity and the existential dread this inspires. It’s here in the literal transformation of figures in He Didn’t Know If She Was There Or Not, She Said She Lost Her Slipper (2018) and Her Shadow Began To Change And Then It Happened (2018). In ink and watercolour, the figures depicted are in various states of transformation, undergoing a metamorphosis that is shocking and inexplicable to others. The paintings are focused small-scale scenes, attended by blotches and amorphous effects of blown paint that add to their ambiguity. Many of Lynch’s works retain this scratchy, weathered, impromptu presentation that lends them more immediacy and the feel of works in progress of an artist keen to record his inspiration.

Metamorphosis is a key theme in his TV show Twin Peaks (1990-2017) and Lost Highway, his 1997 film, in which both male and female leads undergo inexplicable transformations where they appear to literally become other characters played by different actors. Many of the works on display feature figures that exhibit, if not complete transformations, then a process of flux and instability. Is this a materialist, even anti-humanist perspective on shifting identity, echoed again in the jagged, stuttering movements of characters undergoing deep existential crisis in both Twin Peaks and Lost Highway? These are characters often seemingly appalled by their sudden acknowledgement of their own actions.

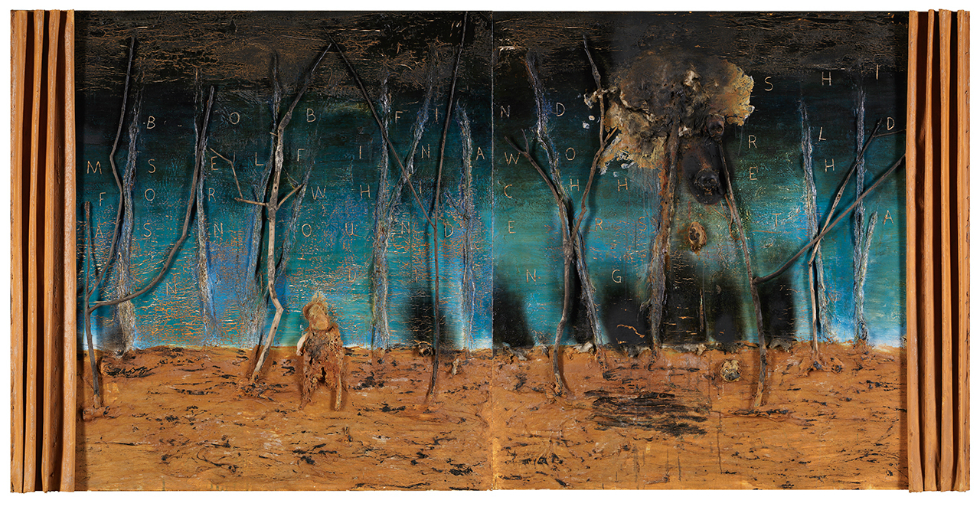

Anxiety is the palpable mood in these chronicles of transformation. Lacking the specific object that pertains to fear, it is instead the awareness of the shift from old ways of living to the new, from corrupted certainties to the incomprehensible contemporary world. This anxiety, alienation and impotence is given full rein in show-stopper, Bob Finds Himself In A World For Which He Has No Understanding (2000). The central figure is crudely drawn with an infantile vulnerability, bare trees appear etched into the barren landscape and sinister, dark forms shimmer on the horizon. As with Mr Redman (2000) from the same period, the scene is flanked by heavily pleated orange curtains – curtains being a device Lynch has repeatedly used to suggest, conceal and reveal in his work.

Fellow painter Francis Bacon’s influence, in terms of his disintegrating figures and framing with crude solid lines is evident, as is their shared preoccupation with the visceral and corporeal. But Lynch’s work takes a more abstract and extreme approach to physicality, often showcasing excrement, organs, innards and effluents. In The Thoughts of Mr Bee-Man (2018), for example, something resembling a turd is situated inexplicably on the canvas. This is part of our interface with the world, part of who we are beneath the domestic veneer – an extreme duality of dreams and corporeality, the ethereal and the solid – it is the full late capitalist hit.

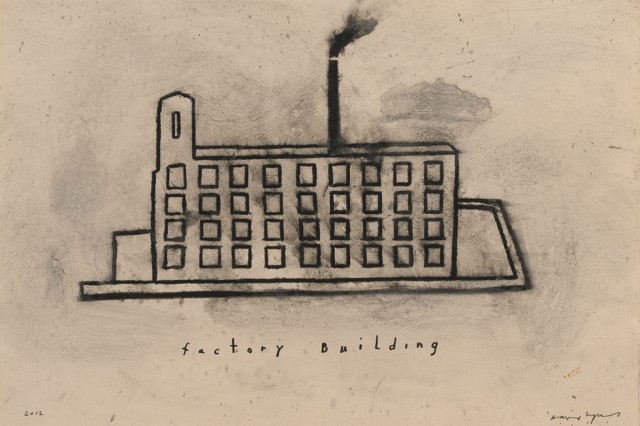

Sadly, the title work itself and the display of illustrated matchbooks are of less interest. Whilst offering further insight into the range and working methods of the artist, they appear one dimensional in contrast to the mixed media and more fully realised recent works. That said, the exhibition is a fascinating opportunity to understand the work of David Lynch in a broader context. The aesthetic that emerges is that of an artist with a compellingly cohesive vision of the ‘Death of America’, and the search for meaningful identity in a strange new world.

Lee Ashworth

David Lynch: My Head is Disconnected continues @ Home Manchester until 29 September

Images: David Lynch, BOB FINDS HIMSELF IN A WORLD FOR WHICH HE HAS NO UNDERSTANDING; David Lynch, PHILADELPHIA (2017) – cropped; David Lynch, FACTORY BUILDING (2012) – in page and home