“Everyone can have a seat at the table, it can’t be as it was.”

The Big Interview: Mia Bays

When film industry research and first-hand experience told her that female writers and directors were being excluded, Mia Bays knew things couldn’t continue as they were. Mike Pinnington speaks to the Oscar-winning producer…

What’s the last film you saw? How about the last film you saw written or directed by a woman? (For me, it was Claire Denis’ High Life. Before that, probably Agnès Varda’s Faces Places.) Does it make a difference whether a film is directed by a man or a woman – in terms of expectation, perception and reception? I ask, because the percentage of male to female film workers is, shall we say, startlingly uneven. As of a 2017 report, for example, women comprised just 11% of all directors. Now, more than ever, seems a good time to redress this imbalance.

One who understands this better than most is Mia Bays. Director at large of Birds’ Eye View (BEV) – an agency campaigning for gender equality in film – Bays has nearly 30 years in the business; an Oscar-winning producer, she has previously been involved in distribution and exhibition. In December last year, Bays spoke at industry-facing film exhibition conference, This Way Up, where she set out the aims of BEV and its Reclaim The Frame initiative. “We want to centre stories that move people, [but] it’s about who tells the story,” she said then. I spoke to Bays recently to discuss how you go about doing that.

BEV hadn’t always operated as it does now. Prior to her involvement, it had been a film festival, “focusing around ten days a year in April at BFI Southbank,” she says. “[But] I didn’t even go to Birds’ Eye View many times. I was kind of resistant – I wasn’t even sure I believed in whether a film festival about just centring films by women helped, or that I even thought it was a good idea.” Were you concerned it was kind of ghettoising those makers, I ask. She answers by way of an analogy: “Yeah. A really good friend of mine is a woman of colour, she’s a poet, and she said something great, which is ‘I get more work in Black History Month than any other time… I often get requests and I turn them down, because I’m black all year round.’ That nails it for me.”

Eventually, though, Bays came around and had been drafted in to run a filmmaker programme called Filmonomics. But, by then, she says, “everyone was fatigued, and they [BEV] were gonna close… they had some money left, which they were gonna give to the BFI, or to Film London, or to the British Council, to just go ahead and spend the last of it on some programme.” At that time (April 2014), she was leaving Film London and BBC production scheme, Microwave. “I’d made eight feature films – we’d done really well on diversity, we’d done really well with socio-economically disadvantaged filmmakers, but we’d done terribly with women. We’d made one film that was directed by a woman out of eight, despite trying.”

This coincided with her having conversations with peers at the BFI, at the BBC and at Film4: “this is 2013-14 and big data studies were coming out. There’s been stasis, or there’s been a drop, in terms of the representation of female screenwriters and directors specifically, so everyone has this shocked reaction – ‘we thought we’d fixed the woman problem.’ We hadn’t.” Any residual reticence about BEV fell away. “I felt a bit turbo-charged. I’ve got some influence, there’s this opportunity here. I’m not interested in running a festival, but Birds’ Eye View has got a name, it’s got some industry recognition, there’s money left – important – not a lot, but there is a bit, and yeah, maybe I can turn this around and make it something else,” she’d reasoned.

If not a festival, though, then what? “We spent basically a year, figuring out what we could be next. What is the evolutionary path? What’s not being done? And, one of the big conclusions, was ‘no one’s having this conversation with the audience – isn’t that a bit weird?’” From this, a new iteration of BEV was born. Taking the existing, engaged audience who were “still interested, still following,” the decision was made to develop the brand into an agency for change, one that would spotlight films by women all year round. “Part of that has involved a very big conversation with the BFI, to say ‘what do you think?’ and the conclusion was, ‘yeah, we think there’s a gap in the market, too, and that, actually, you’re very well placed to fill this.’” Ultimately, this thinking led to BFI backed influencer project, Reclaim The Frame (RTF), the aim of which is to grow audiences for films told from a female perspective.

Screenings are incentivised, with people encouraged to sign up and become ‘influencers,’ attending screenings for free so long as they bring somebody else with them. After screenings, there’s always a Q&A or a discussion, about the film’s themes and the issues it is spotlighting, explicitly or implicitly. Reaching people and getting them in the room is key. It’s about ensuring the success of the films. With titles selected for RTF, “we effectively join the campaign of the film,” says Bays. “We’re supporting the film, the filmmakers, the distributors, the cinema, to help find an audience for this movie.” What’s the gender split in the audience, I ask. “It depends… If you’re an RTF influencer (there’s nearly a thousand of those in ten cities now), they are roughly 84% women and 16% male… but there’s a wider audience there because of the film.”

In which case, does it just as often come down to whether something might be deemed a women’s or men’s film? “When we did Been So Long, the British musical that we toured before it was on Netflix, that [audience] was very young and female; and the highest number of people of colour that we’ve had so far. A film like Birds of Passage, that was much more male. It’s quite easy to predict. Booksmart – very female, young. It really does depend on the movie quite substantially.” Is genre a factor, too, I wonder. “Revenge was a pretty decent representation of men, because of its genre, and actually we had some really amazing conversations about that film, really amazing. But, sometimes, difficult conversations as well. Where a man would admit that there is a point where the film made them think about consent; how a woman is dressed and what she’s done to make you think she’s obliged now to please you. That was great, because it’s really important to have discussions about that.”

This leads us to talk more about that particular audience, and, something I hadn’t expected from a scheme encouraging the platforming of female talent – how to engage men specifically. But, of course, it makes perfect sense. To boost equality in the sector, it must first be normalised. “We do talk quite a lot about what we can do to make the audience more male. Are only the woke ones gonna come to our stuff because they’re comfortable?” she worries. On the flip side, “isn’t the male audience already well served? So, we oscillate between that and then thinking, no, we should do more work. Because I think often there is quite a lot of work to be done around helping men – certain men, let’s say – to feel more comfortable seeing films that centre women.”

It seems strange to believe that there’s still an issue in this regard. But a post on Bays’ Instagram account reminds us that we’re not there yet. After a recent screening, she said: “we had our first major heckle/enraged man experience at a Reclaim The Frame event.” She went on to outline that the man had listened to a discussion revolving around the patriarchal nature of the criminal justice system (including issues of “coercive control, female sexuality and the policing thereof”), when he obviously decided he’d heard enough. “You should be ashamed [of yourselves],” he’d said, “you pretty feminists, being superior, judging people in the past”. “It’s a reminder that this work is important,” concluded Bays’ post, “that there are still many people who don’t appreciate feminism and equality and change, and likely that the kind of leaders we currently have in power just give voice to this kind of patriarchal intolerance.”

Surely, a levelling of the playing field and increased access for those who have previously been denied it, is only a good thing, meaning a wider spectrum of voices and stories for audiences. Bays agrees but is more guarded: “there’s quite a lot of work still to be done when we start to talk about why we centre the female perspective; because it makes the world a better place, makes the cinema environment richer. You still get push back from people. It’s not even binary, it’s not just men saying this, it’s often women too, saying ‘oh, I don’t care who writes or directs. I don’t care who the film’s by, I don’t look at that, I don’t think about it.’ Then you kinda go, ‘well, yeah, maybe you should’. Who tells the story makes a big difference and is very influential in how the individuals and the collective consciousness is represented within that work, and then what it does in the wider world – so we still have those conversations all the time. But, on the whole, there’s not so much resistance.”

And on the other side? What about decision makers? “There is resistance in the industry,” Bays confirms. “The conversations that we’re having are always [about] the industry and the faith it has in films by women. We noticed that recently around Booksmart in the US – why didn’t that work, why wasn’t it a hit? What happened?” The key to things changing, in the short term at least, might lie away from traditional cinema. One of BEV’s partners is streaming service, Mubi, whose offer is generally pretty well-balanced gender wise. “They definitely look at that – they’re a very natural fit for us… But, equally, we’re talking to Netflix about doing another film tour, touring a film in cinemas hopefully before it goes on the platform. Netflix have invested big time in diversity. The last promo they did was all around women, people of colour, LGBTQ. Part of it is the key to their success – making sure there’s something for everyone. The algorithms are that sophisticated, so they have to be.”

So, it’s about the bottom line? “Exactly. That is always our focus – it pays. This is good for everyone, it’s good for the business, it’s how to have a future in the industry. So much is changing so fast, so we have to all pull together and keep up. Everyone can have a seat at the table, it can’t be as it was.” What about more traditional gatekeepers, I ask, are they doing enough? “Yes and no,” comes the response. “Some of them are mindful of this and some of them aren’t. You can probably see from results on certain films – who’s making it work, and who’s hanging on to the old model, which isn’t really working any more. In terms of commissioners, the BFIs and the Film4s and the BBCs, they’re definitely aware. They’re all public funds, you know, they have to be having this conversation.”

After nearly three decades in the business, Bays’ enthusiasm for film remains unbowed. When I ask who else is doing good work in this area, she hardly has to think before reeling off a list “of really good film collectives that are doing a lot of good audience work in a similar space to us”. This includes “people like Caramel Film Club, and We Are Parable, who’ve been doing a lot of stuff in London, but are starting to do more regionally; and Bechdel Test Fest, and Scalarama. Club des Femmes’ another one. I would big all of those up.” Emphasising strength in numbers, she points out that “we’re all in the same space trying to carve out the niche, but we should all lift each other up too.”

Sticking with solidarity, talk turns to the Time’s Up movement, and Me Too. “I’m really glad that Barbara Broccoli and others, like Emma Watson, have been involved in setting up the US chapters [of Time’s Up], brought it home and made good on their intentions to set up a UK arm.” I ask, whether, once Weinstein’s been dealt with finally, is there a danger that Hollywood’s powers that be will decide we should all move on now? Bays’ response is pretty unequivocal. “I think because of organisations like Time’s Up – that really has a lot of power in the US and has a lot of very powerful voices in it – I don’t think the conversation can change; I don’t think people can look away. I feel like there’s not really any going back. There’s more people who are auditing others’ behaviours, or maybe themselves.”

Reaching the end of our conversation, I ask Bays about some of the films she’s looking forward to seeing, for BEV and more generally. What titles should we be looking out for? She excitedly highlights a couple straight away: “We really love a film called Hail Satan?, by Penny Lane, which comes out at the end of August, that’s really terrific. It’s about the foundation and expansion of the Satanic Temple; the importance of separating church and state. It’s deeply political and very, very timely. We love that film.” Another to watch out for, “The Souvenir, Joanna Hogg’s new film is just absolutely sensational. It takes her to another level, and certainly – it’s opened in the US, it was at Sundance – what’s happening to it so far, it feels like she’s gonna be on another level now. You know, that’s a long time coming for her, but boy does she deserve it.”

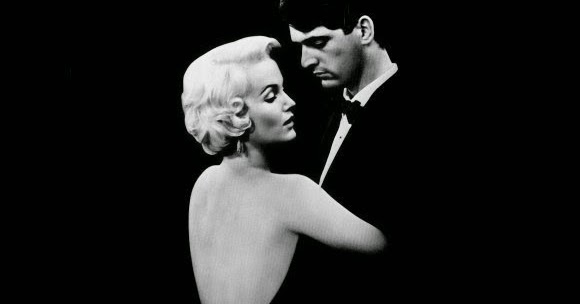

In terms of RTF screenings, they’re in the middle of a Women & Obsession season. A counterpoint, says Bays, to “those wretched, obsessive female cinematic tropes of the 80s – films like Fatal Attraction, Basic Instinct, Single White Female – that frame women in a particular way.” They include a double bill of Smooth Talk, and Dance With A Stranger (both 1985), the post-screening discussions of which so incensed that male audience member I referred to earlier. These screenings form part of a wider reframing of classics which, at the end of the year, sees a reassessment of Barbara Streisand. “We’re going to be taking Yentl, and A Star is Born, and looking at Streisand’s very specific creative contribution to film and how much she was othered,” she says. Othered? How so? “It was the same time Warren Beatty was making Reds, where he’s feted, practically credited in every department on that film.” Meanwhile, when a female star does something similar, “she’s called a control freak… So, we think she’s really interesting.”

The project exposes these disparities without too much fuss, it’s very matter of fact. The simple beauty of it lies in what Bays describes as “taking particular angles and lifting up the female contribution and talking about it from that point of view.” It means audiences – male and female – being exposed to a much broader range of voices and ideas than traditional models allow, being granted alternative perspectives to see things differently. And, after all, isn’t that what the magic of cinema was always really about?

Mike Pinnington

The next Reclaim The Frame event, a double bill of Dance With A Stranger & Smooth Talk, takes place this Saturday, 2pm @ Picturehouse Central, London

Film Still: from Dance With A Stranger (1985)