“A quick, but rich dose of strange fiction.” The Big Interview: Adam Scovell

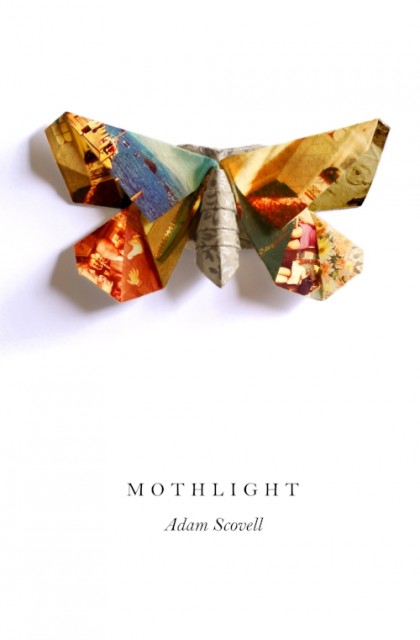

Adam Scovell’s melancholic debut novel Mothlight is rife with the impressions left by place and circumstance, and the tricks memories play. Here, Mike Pinnington talks to the author about the threads running through the book…

“…I feel as if I’m letting a ghost speak for me. Curiously, instead of playing myself, without knowing it, I let a ghost ventriloquise my words or play my role…”

– Jacques Derrida, Ghost Dance (1983)

The Double Negative: Ideas and themes coalesce and flow through the book that can be found in different writings of yours elsewhere. Was there one particular inspiration for Mothlight?

Adam Scovell: I’d been quite obsessed with the theories and writings of Jacques Derrida, the French post-structuralist, and I came across a film where he plays himself called Ghost Dance, by Ken McMullen. In the film, he’s really trying to grapple with this constant striving toward becoming yourself. So, there’s a sort of gap between performing as yourself and what’s considered to be your ‘real’ self. And the way he starts to describe it, the descriptions he used were very sort of haunted descriptions, ghostly descriptions, and from there it became, there was clear potential, at least in my eyes, to apply that theory to something a little bit more obviously ghostly, and a bit more spectral.

You use a Derrida quote as the book’s epiraph and it chimes really closely to the themes in the book, but was it daunting to open with such a heavyweight?

Academically, I’m used to pulling on the big philosophical names. But the quote itself is a quote from Ghost Dance, so in many ways it felt just like having a film quote in there. It was coming across that quote that initially kick-started the idea specifically for Mothlight, but I’ve been wanting to address some of the other things in the book for a while.

I know you best, perhaps, as a critic and academic. What shifts were there between writing narrative fiction and that background? Was this always the direction you wanted to go in?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, and the thing I’ve been working on the longest is writing fiction, it’s just the case that I’ve never really properly shared it before. My writing tends to be known for criticism and essays and that sort of thing, but actually, the thing I’ve been writing since I was a child is fiction. It’s only in the last few years that I’ve found the faith in the ideas that I’ve been comfortable enough with to share publicly and try and get published, so in many ways it was almost like going back to what I knew. At the same time, it’s not necessarily a straightforward fiction writing style – it’s heavily influenced by academic writing… There’s a lot of bridges there between the two.

Was it always your intention to use photos in the book, or did it fall into place once you’d begun in earnest?

Well, I’ve been wanting to use photographs in text for a while. I’ve been using it in an essay form – I find it incredibly interesting and useful to play around with formatting imagery into text. I think it changes both of those things quite heavily. But it just so happens that the photographs used in this book came to me at roughly the same time as I’d watched Ghost Dance for the first time, and there was a dialogue between what Derrida was saying in the film and having this contained life in a box of photographs. They just seemed to work well together, so it became a case of figuring out how text would marry that idea with the photographs, and the first time round, the first draft – which was actually double the length of the book which was eventually published – I think got it quite wrong in many regards. I didn’t get anywhere with agents, or, the people that read it said it was interesting, but it was quite a hard slog, so it took a long while to find the form, and eventually what it needed was drastically cutting down in length, so it became this sort of espresso shot, if you like – a quick, but strong and rich dose of strange fiction. It did take a while to get the form right, definitely.

The photographs are a lens by which the reader can enter the narrative, while the ephemera gives more of a sense of a life?

It makes it more tangible in some regards… There’s a sense that the photographs, or even the little tickets, or other things that appear could just sort of fall off the page; making use of the fact that the book as an object is a quite powerful thing in itself.

Was there a conversation between the life of the person whose photos you used and the narrative they embellish?

It was a basic framework to build upon. The things that were built upon it … were completely fictional. It’s mixing things together rather than pulling things directly from real life. But, certainly, the awe and the sense of mystery that Thomas [the book's protagonist] gets is definitely autobiographical.

This book feels of a piece with your wider interests about place and memories. Do you see it as another outlet for you to explore those things?

“I do, and I think it’s probably going to become my dominant one, because I do feel that the way I want to address those interests is being increasingly shrunk by the restrictions put on criticism and theoretical writing on the platforms that I’m writing, at least. With fiction you have so much more freedom to follow an idea through, and even if it goes to a dead end, I find that in itself interesting. Perhaps it’s a kickback as well from having to have justified every single idea and element from a PhD. You go to the polar opposite where in fiction yes, you have to have restraints, so the logic of it all is put together, but you don’t need to footnote every single aspect and idea, so there’s far more freedom with it, and I find that freedom quite addictive and fulfilling after doing a PhD. It’s definitely going to be a more dominant form with what I do in the coming years I think.

What was your PhD?

“Transcendental Aesthetics in Audio-visual form. I find it very difficult to explain what it was about!”

You’ve talked about Thomas as a ‘shadow version’ of yourself – how much of Adam is in there with Thomas, and also, depending on the answer, did it get quite interesting and weird sometimes in the writing for you?

Yeah – it was interesting, because there is a fair chunk of me in Thomas, I suppose. I’m loathe to say what aspects, but I certainly got cathartic release writing through that character, because it did allow me to explore a lot of different things. There are certainly aspects of me in there. I think it is difficult to discuss what, because sometimes there might be things in there that have unconsciously slipped through. Interestingly, for the next novel [How Pale the Winter Has Made Us], I’ve done a similar thing where I’ve actually lived parts of the novel out very deliberately in the city of Strasbourg, in France, to try and gain some real reactions and conversations with people and the narrator of that book is actually a woman – these techniques and these ideas, and what constitutes you and what doesn’t constitute you can be really interesting and really quite fallible at times as well.

So, how did you do that without it feeling quite studied and contrived, or was it just enough to go through the thing that you wanted the real-life response to?

It was more to do with place, really, because a lot of the time, places are at the centre of my writing and it was about engaging with place in a random way and seeing what popped up, and it took a long while of walking around Strasbourg again and again and again, to figure out what would catch the eye of this character, and in the end it produced quite distinct historical connections and lots of little ones in between, just through wandering around and overhearing conversations. It was then a case of editing it into the mindset of the character that that book is now narrated by, not just me. So that process has been quite tricky, and we’re still working on it in the edit.

You’ve said “death changes place as much as it changes people”, which I felt was a good insight into the book and your thinking more generally…

Essentially that’s the theme of the next few books to be honest with you. I think it’s a good mantra, not just for Mothlight, but the next two novels as well, because their perception of place is heavily augmented – not always for the best – by a death. The narrator of the next book is in Strasbourg when she hears of her father’s death and the narrator of the third book revisits Merseyside because of the death of a school bully that he feels guilty for, so that … is probably a good description of my fiction writing at the moment.

Mike Pinnington

Read the companion piece to this interview – Adam Scovell: On Mothlight

Mothlight (Influx Press) by Adam Scovell is available now