Madiha Aijaz and Reetu Sattar – Reviewed

A new presentation of Biennial works at a pair of venues in Lancashire triggers fond memories while foregrounding urgent cultural issues, finds Siobhán Forshaw…

When we were kids, our mum used the local library as a kind of crèche for my sister and me. She would drop us there after school, before rushing back to finish her shift stitching uniforms at the factory, or sometimes for an hour on Saturday mornings to get her hair done in town. The children’s section of Burnley Library was a magical place. It had great big mobiles hanging from the ceiling – fantastic creatures flying overhead – and squashy beanbags leaking little polystyrene bits over the carpet. It was a haven, where I knew the names of the librarians and where I felt safe and in charge – it was my special place.

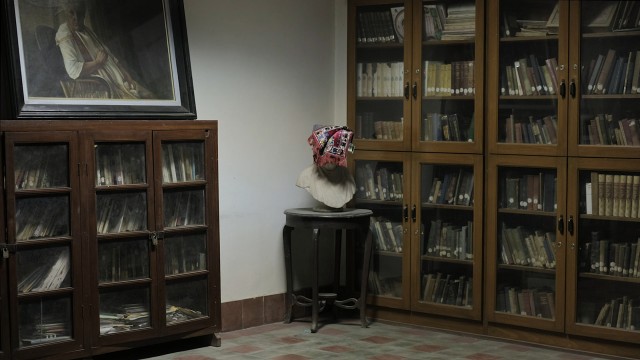

Burnley Library is still open, but across Lancashire, dozens of others have been forced to close in the wake of punitive austerity cuts; 2016 alone saw the closure of twenty-six libraries. The survival of such cultural sanctuaries is at the heart of three video works by Madiha Aijaz, currently installed in Nelson Library as part of the Liverpool Biennial’s strategic touring programme. Aijaz, who died earlier this year at just thirty-eight, presented three meditative and gentle works devoted to libraries in Karachi. They allow us to eavesdrop on conversations about language erasure and reluctant amalgamation whilst the camera flows across the untidy paraphernalia that keeps the libraries going. We watch kettles boiling and papers blown away by cooling fans, whilst we listen to cheerful bickering over the correct interpretation of a particular poetry verse; a funny story told about the habit of Pakistani families to speak to the family dog in English; a lament over the gradual replacement of Urdu with English during television commercials.

Aijaz’s pieces are presented by In-Situ, an organisation that produces contemporary art in response to the people, places and heritage of Pendle. They worked with local community group Mums 2 Mums, who selected Aijaz’s work and who took part in engagement workshops around the commission. Chatting with some of the mums at the opening, they spoke about the meanings of cultural authenticity and aura, particularly about messages they choose to pass on to their children and grandchildren. One phrase that repeatedly came up in response to Aijaz’s work was ‘nah idaar kay nah udar kay’, which means ‘neither here nor there’ – a reflection on the painful reality that when visiting Pakistan, you will be known as a ‘Londoner’ (despite your Lancastrian accent), whilst in your home country, you will not be regarded as truly British. This resonated for me in the recent case of Shamima Begum, the east Londoner who was born, educated and radicalized in Britain, now permanently exiled by a British state that might not find it so easy to remove such rights from a white citizen.

Aijaz’s three videos, nestled between stacks of books in Polish and Urdu, displays about the old textile industry and local Northern dialect, speak to the vitality of libraries as places of connection. Looking around, Nelson Library is host to older gents reading the paper, teens revising for exams, parents reading with their children. When these places disappear, so too do the prospects for mixed communities to share space.

Reetu Sattar’s film Lost Tune is presented by Super Slow Way in the pavilion at Thompson Park in Burnley. She will be taking up a residency with Super Slow Way later in the summer, with further engagement workshops planned for local people. Her piece has a more theatrical edge: musicians sit cross-legged one atop the other on a large scaffolding structure, solemnly playing the harmonium, an instrument that holds deep cultural significance for several of Bangladesh’s minority communities, and which is under threat of decline, in part because of cultural constraints exerted by a controlling state authority. The piece seems to relate the loss of a musical practice to Sattar’s sense of the erasure of free expression in Bangladesh. The scaffolding seems to present the structure of a raga through the logic of a construction that requires foundations and walls before it can have a roof.

It is a great wash of loud, dense sound, which swells and bursts into blasts of bright tones from four shehnais. Within the pavilion space it is imposing and confrontational, and you feel small before it – an inversion of the cultural pressures weighing down on the harmonium, which in Bangladesh is practiced in smaller and smaller numbers. Sattar has described the work as deliberately ‘monotonous’, and it is an unyielding work to witness – a refusal of vulnerability; a reclamation in the face of cultural loss. I was grateful for a presentation from ‘Haych’ (Hussnain Hanif), a local artist who contextualized the piece by explaining the seven notes that build a raga, and giving a generous and full-throated performance over the video. Songs are bodily things, carried on the breath by lungs, mouths and tongues, and Haych’s performance helped me to make a deeper connection with Sattar’s work.

In both installations, we see ruminations on cultural precarity and preservation. Presented within community spaces, they take on new significance, drawing relevance between Karachi and a small Northern town; between the loss of cultural practices in Bangladesh and concerns in British-Bangladeshi communities about inclusion and belonging. It is such a great thing to extend the lives of these pieces beyond the Biennial and into spaces where they may resonate most strongly, but where the communities frequently lack the opportunity to engage with such works in contexts that actually make sense. We are seeing this approach develop elsewhere in institutional programming: the touring of a Gentileschi masterpiece into women’s prisons and girls’ schools has created opportunities for a greater understanding of how the cultural industries work. In the face of ever-narrowing cultural provision outside of major cities, these programmes are crucial: let’s hope it proves to be more than a trend.

Siobhán Forshaw

Madiha Aijaz and Reetu Sattar continue until 30 June at In-Situ and Super Slow Way respectively

Images from top: Reetu Sattar, Haranu Sur (Lost Tune), 2017-2018, Image courtesy Sayed Asif Mahmud; Madiha Aijaz, Memorial for the Lost Pages (film still), 2018