As seen on screen: Art and Cinema – Reviewed

The relationship between art and cinema is as old as the silver screen itself. Ashley McGovern reviews a new exhibition exploring this tradition…

Purveyors of clickbait like to play amateur detectives, luring us to move over our cursor and land on some hyperinflated exposé. On rare occasions, they venture into the arts. BuzzFeed, Ranker et al. at some point will have published an expendable little piece about how world-class filmmakers have lifted their compositions straight out of famous paintings or photographs. Written to be swiped rather than read, a slideshow usually ensues; on one side is Hopper’s House by the Railroad (1925), while on the other is a movie still of Norman Bates’ virtually identical Carpenter Gothic pile from Psycho. Then maybe Alien’s alien compared to one of Francis Bacon’s screaming Popes. And inevitably rounding out the slides you’ll find the sinister twins from The Shining alongside Diane Arbus’ photograph, snapped more than a decade earlier, of painfully plain twin girls in matching dresses. They say no more than ‘here’s some art, here’s some films’. Foreign cinema is typically excluded, though that’s not to say there aren’t plenty of ripe examples. A result of the meme decade, said pieces are designed to be read at pace with little attention, hooking us with a famous movie and adding in populist, time-killing art history; a pop Panofksyan exercise, you might say, in spotting how iconography travels across different media. And this is perfectly fine for ersatz reading.

One might, however, expect more from an exhibition. Especially one that purports to explore the same territory as the BuzzFeeders, though this time in reverse: how cinema has returned the favour and inspired artists. As seen on screen, originated by the Arts Council and now showing at the Walker Art Gallery, must have been devised, approved and curated during a fire drill. The show is incoherent and severely undermines its own exploratory premise at nearly every turn. As seen on screen’s conception of cinema, its technicality, its unique editing, its auteurism, is sorely limited, so fragmentary and taken for granted as to be practically a secret. There are small gestures to film noir, fugitive hat tips to British classics, suppressed nods to old Hollywood. With nothing to guide you, a feeling that cinema is the greatest mass medium, whose status is for artists both enviable and yet aching to be deconstructed, is just about discernable. Its inclusion of cinema is like a Hitchcock cameo minus the rest of the movie, winking, fleeting and devoid of overall unity. The most the curators offer in the way of rigour is a conspicuous truism: cinema has been and still is influential. No attempt is made to define or even complicate what this really means for visual artists; finding a nuanced theme or proposition in all this is trickier that coming up with a gender neutral title for His Girl Friday.

Take Venice Kimono (2012), Anthea Hamilton’s digital print of John Travolta’s face (taken from Saturday Night Fever? We’re never told) on the back of a satin kimono. The garment rests on a dainty piece of steel scaffolding, flowing down like a flag or silken stage backdrop. What is this trying to say? It could be about how movies manufacture pinups, or perhaps the wearying process of industry merchandising – for the record, it doesn’t successfully convey anything of the kind. Nevertheless, the silly semi-sculptural installation, the willowy inanity negate any attempt at appreciation. This wouldn’t sell at a Scientology benefit auction and contributes nothing of worth to this show. With a diverse range of artists on display, make a quick mental tally of styles as you’ll find no help from the gallery material. I counted roughly four phases; there’s British Pop, 1960s Conceptual art, neo-Conceptualists of the 1990s and some contemporary video art. Each generation, as one would expect, has their own valuations of cinema. The neo-Conceptualists have a better time deconstructing film, attacking codes and ideologies, while the Pop artists are adoring cinemagoers, their big screen a limitless silver sky of stars and starlets.

Culled from the heyday of British Pop, the simple but subtly dense patterning of Eduardo Paolozzi’s Wittgenstein at the Cinema Admires Betty Grable (1965) at least offers a sense of the spellbound moviegoer. Notes at the base reveal how the great philosopher loved to relax after lectures by watching the latest Hollywood flicks – Betty Grable and her $1 million insured legs being a personal favourite. As a collagist and printer, Paolozzi demonstrates a brilliant ability to suggest shadow and depth by changing the angular grain of his patterns. There’s no real way of identifying familiar shapes, the sinuous outlines resemble cartoons – a mouse’s head, an oversized gun – and yet the effect is entirely serious. The visceral rush of sitting in front of moving images comes across. Nothing else in the exhibition conveys this.

So what other cross currents and themes do we get? Let’s try the all-important photographic element of film. Movies are montage, and transitioning from one still requires the director to be a manipulator. Hard proof of this malevolent magic was discovered over a century ago in a simple experiment later known as the Kuleshov effect. With Milgramesque glee, Russian filmmaker Lev Kuleshov showed a test audience six shots; the pattern was one of matinee idol Ivan Mosjoukine’s inscrutable face followed by a random scene or object, this sequence being repeated three times. The objects were a plate of soup, a girl in a coffin, a woman on divan. Secretly, Kuleshov used the exact same image of Mosjoukine every time, and yet the audience was convinced that his reactions were related to the stimulus supposedly situated in front of him. In short, proof that directors and editors wield mighty powers of selection.

This haunts two pieces, one a series of photographs from a lost Polish film called Europa made in 1932 by artists Franciszka and Stefan Thernerson. The movie itself is no longer with us but the photographs were salvaged and turned into a Dadaist photobook, some pages of which appear here. The final one of naked upper waist, loaf of bread and face front lit in darkness in a vertical strip is almost identikit Kuleshov, but as we don’t have any real context the meaning is lost. The montage comes off as a piece of derivative Dadaism, when I’m sure the original movie, apparently about the rise of nationalism in Europe, wasn’t in the slightest.

Another draft of Kuleshov is found in Sam Taylor-Johnson’s Red Snow (from Screen portfolio) made up of two photographs, one of an intense bearded man looming, shot from beneath, another of a woman lying dead-eyed in the snow. Numerous possibilities foment in the form of accusations: what has he done, what does he intend to do, etc. Of course the images are unrelated and like Kuleshov’s dogs we rush in to provide an interrelated meaning. The images are not scaled to one another or even positionally related on the canvas, and the deliberate misplacement, the apparent editorial carelessness spotlights the visual masterminding of a director very well; it’s a minor but interesting work.

If some artists wallow in the medium, others are trying to break down the notion of ‘studio’ cinema. Yet only the gallery text revealed to me what Fiona Banner’s The Desert (1994) is attempting to achieve. The work is beyond facile. The Desert consists of a written retelling, all in plodding third person, of the entire plot and dialogue of David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia – that’s the whole 3 hours and 48 minutes. The wall text tells us that she has bravely included the word ‘wog’, a reminder of the residual racism of certain of the movie’s screenwriting and casting choices. It’s puzzling why anyone would stand in front of such an asinine attempt to capture the pace of film. Strangely, our captioner doesn’t blanch at the prospect of telling us that Banner has set up her own press so she can publish her work between covers, one of which is THE NAM, a 1000 page pseudo-transcript of a handful of Vietnam war films. The imprint’s name? The Vanity Press.

Disappointments continue in the House of Women, a 16mm film by Michelle Williams Gamaker. British cinema is under scrutiny again, though a little more effectively this time. The film is a series of short interview/auditions with first-generation British Asian women. The premise is that they’re trying out for the role of dancing girl Kanchi in Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus, a part with all the nauseatingly problematic casting of a bygone era. Originally taken up by a white actress, Jean Simmons, Gamaker is out to show how this choice and lines from the script reveal the arrant subservience and colonial arrogance beneath the movie. At first we get a series of brilliant interviews about expat life, the anxieties of acculturation and all the smart, quiet anger of women fighting against misrepresentation. Sadly, this tapers off into a needless experiment with lighting and a read-through oration that does nothing to contrast the living stories of the three actors against the original. You have to search independently to see Simmons’ embarrassing portrayal, and the rich details of recalled heritage fade away as the enterprise exhausts itself.

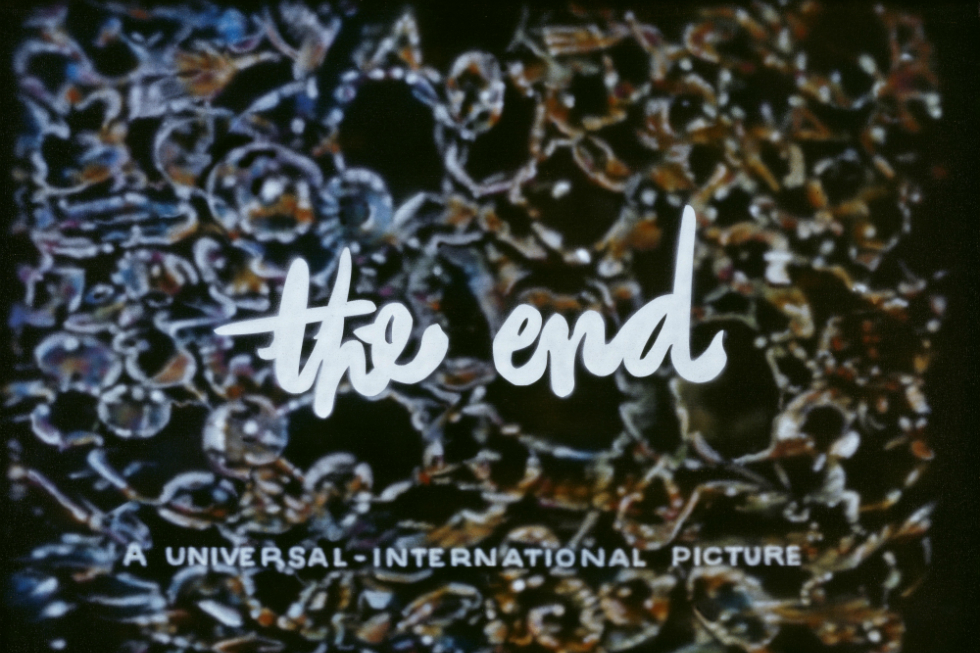

Elsewhere we get a vaguely amusing slow motion film by famed video artist Bill Viola, a crazed rap animation called A Nightmare of BAME Street, a handful of screenprints. By far the most resonant work is The End/Untitled, series by Mario Rossi. There are five paintings showing the final shot, literally ‘The End’ still, of movies like Psycho, True Grit and Madame X. Lushly painted in the centre of the canvas, the textual cue provides a vivid centre against the backgrounds that are painted in the same fashion as Gerhard Richter’s blurred portraits. Rossi is playing with deep focus cinematography, illustrating how old films ended by literally deteriorating the quality of the image. Part of a series of more than a hundred final still canvases, usually hung by stacking them on top of each other like a multi-screen, more of these would have been welcome.

Emerging from the cutting room of this exhibition are some half-formed ideas, most of them old hat. Examination of montage and seeing how art, especially painting and screenprint, can capture the kinetic field of the cinema screen has been done many times over – the debates are older than old man Kuleshov. At least for clarity of purpose, the clickbait crowd have beaten the galleries this time.

Ashley McGovern

As seen on screen: Art and Cinema continues at Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, until 18 August 2019

Images, from top: The End/Untitled series 1996-2000 Mario Rossi, Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist; Venice Kimono 2012 Anthea Hamilton, Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © the artist; House of Women, 2017 (production still), Michelle Williams Gamaker, Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © Courtesy of the artist and Tintype, London