“An artwork’s a key that could unlock you-don’t-know-what.” The Big Interview: Tim Etchells

I was a young graduate when I first saw one of Tim Etchells’ neon artworks. ‘WAIT HERE I HAVE GONE TO GET HELP’, it said, in siren red text.

Wait Here (2008) seemed to sum up how I felt about starting out as an artist and, inevitably (as I was skint and didn’t know what the hell I was doing), moving back home to my Mum’s flat and gingerly signing on. Etchells’ work does that: it seems to say something amusing or cutting, personal, whilst (on the face of it at least) being fairly broad and relevant to everyone else at the same time.

He’s a multidisciplinary artist, nimbly dipping into text, sculpture, sound, performance, drawing and installation. Writing is, and always has been, at the core of his practice, reflecting a life-long experimentation with words and language. Anyone interested in developing their ‘voice’ should get hold of his essay On Performance Writing, from the book Certain Fragments (1999), which also happens to be a good overview of his time as the artistic director of Forced Entertainment: ‘Britain’s most brilliant experimental theatre company’ (the Guardian). In it, he talks about stealing words (‘a thieving machine’), sampling, mixing and pasting, borrowing phrases that end up, years later, in his scripts.

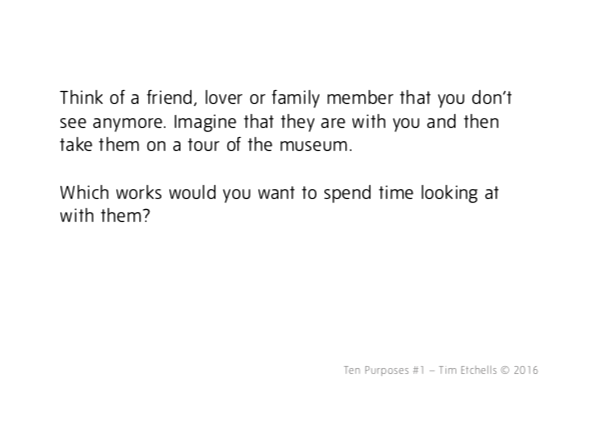

As you’ll be able to tell from my interview with Etchells, below, I’m a fan of his Tate Exchange commission, Ten Purposes (2016): a pack of ten instruction cards for visitors to use in the gallery. Pick up a card, read it, follow the prompts. They ask you to forget everything you see in the museum and, instead, think about another place or someone that ‘changed everything for you’; another asks you not to look but to listen to a friend describe what artwork they’re seeing. They provoke – maybe even emotionally manipulate – you into looking, really looking, at your surroundings, and relating what you see back to your own life.

I was intrigued to hear that Etchells was curating an event called Strong Language in Sheffield, where he lives part-time when not in London. Part of literature festival Off The Shelf, the event featured one of my favourite sf/horror writers, M. John Harrison, plus Tony White from Piece of Paper Press (PoPP), and artist Selina Thompson’s Race Cards project. Strong Language attracted other writers like me who treat writing as a creative practice; we talked about what writing could be and saw it published in alternative shapes.

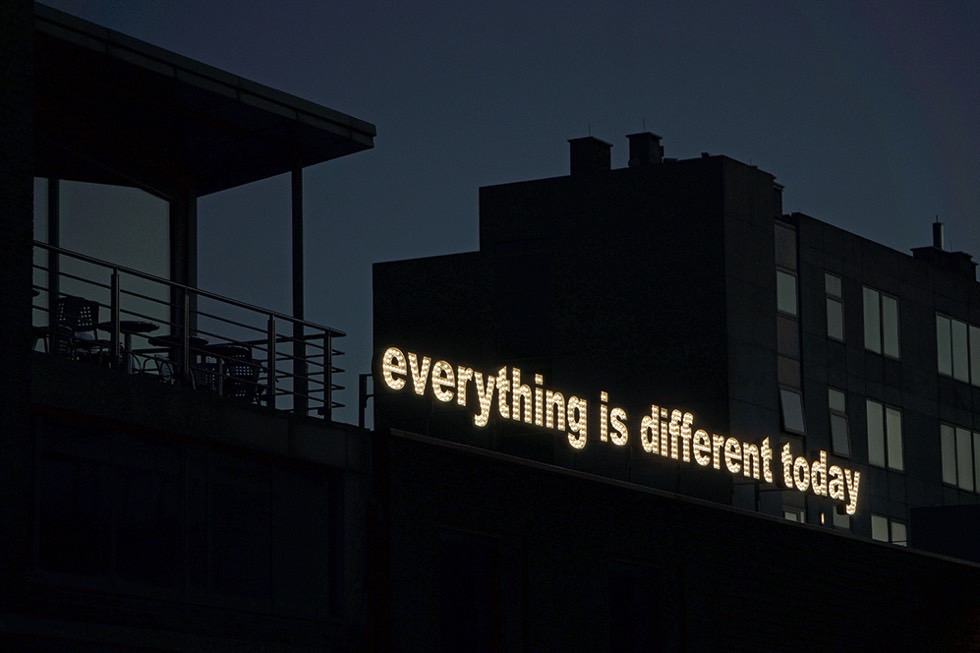

Our interview took place over a hummus-heavy lunch in the Site Gallery café, underneath his new rooftop LED commission, Different Today; conversation quickly turned to what Etchells’ writing is doing to/with the viewer.

Laura Robertson: Who, or what, did you first think about when you were putting together the programming for Strong Language?

Tim Etchells: My first port of call was to think about PoPP, because it was a project started here in Sheffield, in the period of time I guess after Tony had studied at Hallam [University]. It has a strong Sheffield connection. It made sense then to use that as the backbone; I talked to Tony about an exhibition of the different books, coming to read, and commissioning some new PoPP editions. We had a curatorial conversation about who would we invite to do new books.

That must have been some fun – did you have a shortlist?

Yeah we did have different thoughts. We were both keen that it wasn’t just ‘writer writers’, that it was a mix of different people.

PoPP is such a unique format: they fit in your purse, and are almost throwaway. When Tony explained the processes and restrictions in the Strong Language panel discussion [A7, limited edition of 150 copies each press, posted out to subscribers] it became clear why they’re valuable.

They are a weird combination of disposable, throwaway, one bit of paper, but also very precious. I think anything small has that slightly fragile quality. I like that.

They’re also great introductions to writers – you may never have read Mike John Harrison’s work before, and his PoPP book is a jumping-off point. Harrison in particular was a good choice, because he dives into sf, horror, short stories, flash fiction… He’s such a versatile writer.

Yeah, we were keen to have a range of people coming from different places; Mike and Courttia [Newland] are both published fiction writers; Joolz [Denby] is legendary from the ‘80s as a punk poet, coming really from a different cultural scene, she’s amazing; and then Selina [Thompson] is a very interesting performance/installation maker. I think about writing, and I’m enthusiastic about people who come from literature and experimental literature. But I’m also enthusiastic about visual artists who are working with writing, people coming from poetry, people coming from all over.

Considering the area, and Site Gallery – which has recently been refurbished, and is next door to a big artists’ studio complex – there’s an audience in this locality that have a real interest in crossover genres, music, performance, art and writing, theatre.

Yeah, what Tony was saying, as a coincidence, three of the PoPP writers are in the exhibition [Liquid Crystal Display, at Site]. There was no design in that. It’s just that the intersection of interests is tangible.

Maybe that’s because Tony has good taste in collaborators…

I really want to ask you about Ten Purposes [‘a set of instructions to carry out within and beyond the gallery’]. I’ve used it with many of my students as a way into talking about art, and a way into art criticism. On a very basic level, it’s an icebreaker; the cards help to start a conversation about connections between art and real life. But it also relates to the type of art and criticism that I’m interested in, that explores memory, emotions and personal experiences. You manage to condense huge questions into ten actions. How did you tackle the project? It seems a good way into understanding your practice and the audiences that you work with.

I liked doing those; it was a certain crystallisation of my thinking of what an artwork can be. In this case, I’m approaching it as a key that could unlock you-don’t-know-what. In that sense, your job is to create something that has maximum potential to cause ripples in another person.

In those text instruction works, and in something like the text sculpture on the roof here at Site – Different Today – what’s important to me is the potential for the work to open up space. Rather than focus the viewer down with a statement the work tries to create a terrain or space for different thoughts.

What type of terrain are we talking about?

I’m drawn to things that have a contradictory possibility. The full text of Different Today is the simple statement ‘everything is different today’; most people read it as a rather utopian thing, it’s got a bubbly aspect to it. But if you think about it for any length of time, there’s also something uneasy about the statement. The ground is shifting, in what ways is it shifting, the building’s changed, Sheffield’s changed, there’s a perpetual set of movements going on, culturally, politically. Not all of that is good. There’s a disquieting element to the change and the idea of constant change. I always like these things that open a sort of disquiet as well as more pleasurable thoughts or scenarios, I like the dynamic of invoking both things together.

I’m interested often in creating a space where people enter quite private negotiations. Out of a lot of those instructions at Tate, the one I really remember is the one about imagining a friend you don’t see anymore.

That one really hit a nerve with me:

‘Think of a friend, lover or family member that you don’t see anymore. Imagine that they are with you and then take them on a tour of the museum. Which works would you want to spend time looking at with them?’

You’re forming a very powerful space in which to look at art, things that you may never have seen before that suddenly take on a new significance. Did that come from a personal place?

I’m fifty-six, so there’s a lot of people who I have been very close to in my life that I don’t see anymore. Whether there’s a drama there because we fell out or broke up, or ‘what happened to that person, I don’t remember’, or they died. Lots of that accumulates in your life. Of course, we carry those people with us. It’s not unusual that you go to see an artwork or an exhibition, and maybe you have a history with that work or artist that connects you with another person, or there’s something about that particular work that reminds you of them. It can be heavy. A good friend died last year, so I could go there, and try to think about him, in relation to that task. But I could also think about some mate from school that I never see – what would they think of this work, what would I say? It can be heavy but it doesn’t have to be. I don’t like work that really insists. It’s like when someone says ‘tell me a secret’. You’re like, I don’t think so, no. But creating a territory that leads you in… You go there more willingly and with more investment than if the work is yelling at you.

But most people I’ve shown that card to say ‘ooooff’ – they automatically ‘go there’ to the most intense relationships they can remember. No, the cards aren’t insistent, the language is reflective and calm, but I do think of them as provocations. Do you?

I think you’re right about the language; there’s something about the wording in those works. It’s something I’ve been working on for a very long time – figuring out a use of language that’s calm, clear, vivid, but it’s not asking too much. It’s not performing at you with a lot of intensity. To connect it back to Strong Language, I think Mike [John Harrison] is a brilliant reader. Most writers over-perform what they’re doing, and as a listener that’s tricky, because it closes down space. Whereas Mike adds very little when he reads, he just articulates what’s there – not in a way that makes it sound dead, but in a way that’s sympathetic to the mechanics of the language. It’s an approach that just lets the language be there and do its work.

Those provocations for Tate were made to take you deep into something, but taking care not to demand or yell. The idea, the request of the text is there in a fairly simple and straightforward way. As a writer that involves a lot of choices, a lot of working on the language to get it to be that kind of offer. You have to be very precise.

Would you see Ten Purposes as a form of interpretation, as galleries and museums use the word?

I see it more as parasitic. It’s doing its own work. When people are walking around a museum, you don’t know what the hell they’re thinking. And that work, in a way, says yeah, you don’t; here’s some of the ways that this could go. Let’s activate this space.

You use the word ‘activate’ a lot. You’re making me think about relational aesthetics. Are you of the opinion that other people activate your work?

I think you can usually understand the work as a proposition, or you can see it as a set of coordinates, or a constellation of energies, held in a kind of suspension. But it always needs a viewer or a reader to activate it, to experience it. That’s always a negotiation. The work in a room with no person to read it, look at it, hear it…

If a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it…

[Laughs]… It’s just waiting to happen. But it will only happen – whether it’s a book or a sculpture or a video or a performance – in that moment of, essentially, performative exchange. I used to feel across the range of my work, erm, that it was a little incoherent to me why I was doing all the different things that I was doing.

At what point are we talking about here, was this at a particular time in your career?

In the ‘90s probably. I found it difficult to talk to people from different worlds. If I was writing, I was talking to writers about writing, and if I was making a performance I’d be talking to performance makers. Some time in the later ‘90s or the early ‘00s I started to understand that it was all part of the same enquiry, and at the basis of that enquiry is this understanding of the artwork as a proposition or as a set of materials that need to be activated by a viewer or viewers. The trick is designing those materials in such a way that are vivid and generative, they make something happen.

If I think about those Tate instructions, the idea is that they make something happen. I don’t know what they will make happen, although they’re designed in a particular way, so if you ask people to think of an absent person, you kind of know where you’re heading. But it’s open. You’re leading, you’re boxing a space, but what happens inside that space you don’t know. That’s what I like.

Did you ever go round the gallery with other people and those cards?

No, no.

Did you get any feedback on what they were like to use, what happened as a consequence?

I had feedback; people wrote or they fed back to Tate, I did hear anecdotal stories. The work contains a certain amount of information, it’s a limited amount. Because it’s a fragment, it’s not finished, it demands that the viewer do the work of completing, to fill the spaces that it creates. They provide ‘that’ much [gestures small size], but to be fully legible the other part needs to come from somewhere else; it could come from the viewer, or in the way that the viewer reads between the work and the environment, or their own history. I’m really interested in the idea that what you make isn’t a brick wall, it’s more like a set of floating points.

Another neon work of mine just says: ‘Let’s pretend none of this ever happened’. The ‘this’ isn’t specified, it’s not clear whether that means this afternoon, all the shit that happened this week, the twenty-first century, white people – who knows what it’s referring to. Your brain has to do that. That work was installed in Bloomberg space in the East End, and of course there, it’s hard not to think about Mike Bloomberg’s company’s gallery, the financial crisis. The same year it was installed in Blackpool on the roof of the Grundy, not long after the Brexit vote…

Yes, I saw it at the Grundy, it seemed like a very pertinent time. Do you try to control exactly where and when your work’s installed?

Sometimes it’s considered and sometimes it’s not. That same work was installed in Lisbon actually, on the front of the National Theatre, which I thought was very funny as an experimental theatre maker. I’d love to put it on the National Theatre here!

After the Lisbon presentation of the piece I got an email from an American tourist. Their tour guide had shown them the work and explained to them that the site of the theatre was [also] the site of the Spanish Inquisition in Lisbon. So this tourist wanted to know if the work was referring to that. I didn’t know this fact about the location, I wasn’t even sure that it was true… But I did write back and say that the work is designed to trigger these kinds of connections and, if you were thinking of it, you can’t be ‘wrong’.

Are people surprised when you say things like that? I get the impression that most of us feel like we should be guided into understanding art.

I do think that’s a bit of a problem. Here, you’re taught art or literature as if it’s a puzzle of some kind; to find out what the artist or author really meant to tell you.

Of uncovering, finding clues… That’s also a natural response.

I think that is natural, it’s fine. What’s weird is if you would think there was a right answer, then that’s troubling. I don’t think that’s how art works. You wouldn’t necessarily expect the artist to be the one to rubber stamp the meaning; if I look at a work and think X, Y or Z, I’m not asking the artist to say whether I’m right or not. I can talk about a work that I’ve made, and what for me it activates, but if you said you were thinking about something else I wouldn’t argue with you – the work’s an object. The work generates thoughts and feelings. I don’t think it’s the artist that one should be looking to, to say correct or incorrect, two ticks or one tick. School is a bit like that.

Maybe that’s where it comes from, school; that lack of confidence, feeling like you don’t know enough to make up your own mind about something. That bleeds into culture, and makes us feel insecure about voicing opinions about art.

It’s interesting to read about works and to understand the context of them, and other people’s interpretations of them, but the thing that’s fundamentally interesting to me is the encounter with the work in an unmediated way. In general, a culture of explaining things to people reinforces the sense that they don’t know and aren’t qualified to know. How do you give people the confidence to look? And to speculate around their looking? In a way, that’s what the instructions for Tate were doing; they were saying your presence here is legitimate, the baggage you’re bringing is legitimate, it’s all in the room.

As told to Laura Robertson

Laura saw Tim Etchells’ curated three-day event, Strong Language, at Site Gallery in Sheffield, Fri 12 October to Sun 14 October 2018 – as part of Off The Shelf annual literary festival

Image credits from top: Different Today (2018), courtesy the artist. Piece of Paper Press at Strong Language, credit Chris Saunders. A screenshot of a Ten Purposes card. L-R: Tim Etchells with Janette Parris and Tony White at Strong Language, credit Chris Saunders. Let’s Pretend (2014) at the Grundy, Blackpool

Further reading on M. John Harrison: “Distinct stories that resonate, disturb, shock and confound…” You Should Come With Me Now: Stories of Ghosts — Reviewed