Field Trip: Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain

On a recent trip to Bilbao for the final days of controversial exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, Linda Pittwood found a complex fermentation of global and local politics…

Before you can enter the galleries of Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, you have to navigate the exterior of the building. This can mean being engulfed in by Fog Sculpture #08025 (F.).G.), 1998 by Fujiko Nakaya, listening to several repeats of New York New York played by, if I am kind, a mediocre clarinettist, avoiding buying the unofficial Louise Bourgeois’ spiders spun from wire that seem to crawl from everywhere, or spending way too long trying to get a perfect selfie with Jeff Koons’ Puppy, 1992. But it is also a process of understanding the place and of place-making. Museo Guggenheim has now been open for 21 years. It’s a good time to ask, what impact has the venue had on the city, and what impact does the city have on how we interpret the art within?

It is easy to assume that culture, led by the Guggenheim’s arrival, has reinvigorated the largest city and defacto capital of the Basque country. I visited in a still-warm September, falling in the gap between summer shows and autumn programming. Perhaps because of this I was left feeling that the cultural offer of Bilbao, as the artist collective ZAWP have incorporated into their acronym, is still a work in progress. The more I looked for art, the more I found the closed doors of Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao, currently revamping to relaunch next year, or walking for miles along the tangled, steep, intriguing streets of the San Francisco neighbourhood, failing to find SC Gallery + Art Management.

Like many tourists I caught a plane from Manchester one afternoon heading to this autonomous region in northern Spain for the Museo Guggenheim Bilbao (which had 1.3 million international and local visitors in 2017). Specifically, I came to see the exhibition Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World, in its final days. The exhibition has worked hard, opening at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 2017. It weathered a storm of controversy about use of animals in artworks; both animals (insects and lizards) in gallery and animals (copulating pigs) captured in video. New York made concessions.

But possibly a more controversial question was whether the Guggenheim’s response was to spin the events into a PR opportunity and exploit global headlines. The animals are mostly back, except that the lizards populating the eponymous Theater of the World (1993) by Huang Yong Ping are fed their usual diet of insects outside of gallery opening hours rather than as a spectacle for the consumption of viewers.

Art and China after 1989 isn’t a show that slots with curvaceous, immersive ease into the Museo Guggenheim, as Richard Serra’s copper-coloured permanent installation The Matter of Time (1997, pictured above) seems to do so effortlessly. This large show, including the work of more than 60 artists, is complex and context-specific, challenging and fragmentary. For the first time, many of these artists are situated within the two main Guggenheim venues, which together crudely form the axis of Western 20th century modern art: Picasso to Warhol. These venues are the underpinnings of a canon that Chinese art, along with contemporary artworks the world over, both reinforce and subvert.

Whilst modern art was ‘happening’ in Europe and America, Mainland China was ‘closed.’ Communism under Chairman Mao controlled art, culture, gender, politics, daily life and economies of information. This gives contemporary Chinese art its own particular trajectory, processing a legacy of trauma, ascending from China’s own early-20th-century modernism and now fully part of complex-connected globalization. 21st century China is a Communist country with capitalist characteristics, and its own specific “stakes” as opaquely put by Alexandra Munroe, Samsung Senior Curator of Asian Art at the Solomon R Guggenheim Museum and co-curator of the show. The stakes are alluded to in the gallery interpretation of Art and China after 1989 but not always unpacked.

Apart from the somewhat castrated Theater of the World itself, the show’s principle works are Chen Zhen’s Precipitous Parturition (1999, pictured below) and his Fu Dao/Fu Dao, Upside-Down Buddha/Arrival at Good Fortune (1997). In New York, Precipitous Parturition hung in the negative space of Frank Lloyd Wright’s central rotunda. But in Frank Gehry’s Museo, there is height, width and length within the temporary exhibition galleries to accommodate a 20-metre dragon made from rubber bicycle inner tubes, aluminium, plastic toy cars, metal, fragments of bicycles, silicon and paint. Precipitous Parturition, makes mythological the all-too real reality of factories, consumption, landfills and waste. Next to it is Chen’s Fu Dao… meditative structure comprised of steel, bamboo, resin Buddha statues, a washing machine, a computer monitor, tires, a bicycle, a fan, a chair, household appliances, other found objects and string. Chen brings a vital spectacle of scale to this survey of contemporary Chinese art.

The show is framed by the end of the cold war and the Beijing Olympics in 2008. My understanding of 1989 is that it was only one date within a process of the cold war dismantling; whilst within China it vaguely marked a decade on from the death of Chairman Mao and the re-introduction of a market-led economy. Significantly, it was a year that began with optimism for contemporary artists in the PRC, with tacit acceptance for their practice demonstrated by being permitted to stage temporary exhibitions. But only a few months later the massacre of protesters at Beijing’s landmark Tiananmen Square renewed suspicion towards experimental art strategies, leading artists to de-politicize their work and to produce exhibitions in apartments and artist communities. The implicitly-political framing of Art and China after 1989 is perhaps what has leant it a sombre palette. The show is a world apart from the carnival atmosphere (‘inauteri giroa’ in Euskara, the language of the Basque country) outside the gallery walls at the Museo.

Some things are, arguably, missing from the exhibition. It is unclear whether female artists were marginalized because of the framing of the show or for some other reason. Many important artists are either not here (Cui Xiuwen, Xing Danwen, Chen Lingyang, Xiao Lu, to name but four) or unrepresentative pieces by them have been chosen (Kan Xuan, Lin Tianmiao, Yin Xiuzhen and Cao Fei). The latter group make bigger, more nuanced and funnier work than the examples you see in this show. In Lin Tianmiao’s Sewing (1997), a thread-wound sewing machine is a thrill to see in its precise tactile flesh. Kan Xuan’s KanXuan Ai! (1999) video is best seen in the gallery, because the artist is concerned with every aspect of the presentation of her works.

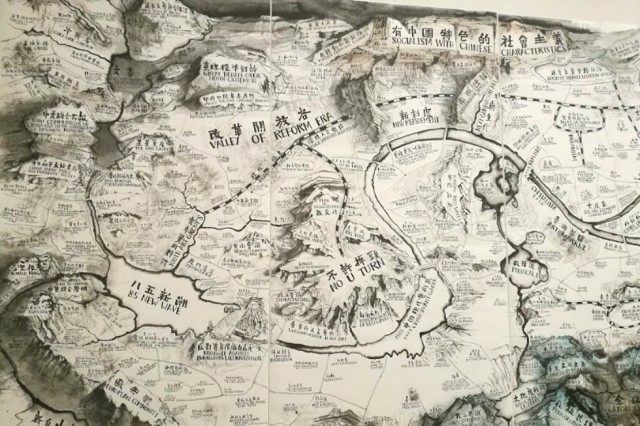

Meanwhile of the men: Ai Wei Wei is here dropping his pot and with it laying down questions about authenticity, value and cultural identity. Xu Zhen’s gaze in Rainbow (1999) focuses on the harm that unseen violence has left behind. Zhang Peili’s hand scratches furiously, repeatedly. And Qiu Zhijie (below) ostensibly gives us a map to understanding, but ultimately demonstrates that curatorial practice and cartography are both disciplines of omission as much as representation.

Towards the end of the exhibition, the pressure to contextualise and to explain the relationships between artists and movements becomes heightened and threatens to drown out works that should have been given more air. Cao Fei’s RMB City (2007), a work that blurs the lines between life, second life, documentary, internet and gallery-based art, is confined to a corner between resources such as interviews on video screens, copies of publications and other methods of exhibition/art history making.

The final note of the exhibition leaves questions hanging. The Beijing Olympics was, in tourist terms, Beijing’s Guggenheim. It brought to the world’s attention everything that China’s capital had to offer, including world class cultural venues and architecture such as the National Centre for Performing Arts alongside historical monuments beautifully preserved. A theatre of the world in one city. In Art and China after 1989, the Olympics was illustrated by Cai Guo Qiang’s opening event firework display, Xijing Men’s satirical response to the event and American artist Sarah Morris’ film Beijing (featured, top), which folds together flocks of geese and the Olympic stadium. Like Morris’ film itself, this triangulation of perspectives with no single argument feels a little baggy as a finale.

Before I left the Museo, the communications team at the gallery urged me to look at another temporary exhibition, Joana Vasconceloa’s I’m Your Mirror. They described the work as “visual”. However, Vasconceloa’s multi-sensory-maximalism only serves to underscore the impossibility of communicating the complexity and extent of 20 years of contemporary art from China in one show, even before you try to fit it into the global picture by exhibiting at two very differently-toned Guggenheim museums. Perhaps the team wanted me to get a better sense of the city itself than Art and China after 1989 could offer.

In fact, it was only after I abandoned my pursuit of art that I was free to enjoy Bilbao for its many other strengths. Mostly this was food, with many vegan choices available. I wrote notes for this article sat on a bar stool at Pizzeria Trozo eating a most enormous houmous and courgette pizza, drinking a Boga garagardoa craft beer produced by a local cooperative, and feeling overwhelmingly content. I had excellent coffee at Bihotz Café and ascended the mountainside using the Artxanda Funicular (cable car) for panoramic views of the city, glistening and perfect in the September heat.

Outside of Museo Guggenheim and Art and China after 1989, I did not enter a space devoid of covert political messaging. Spain’s political divides are threatening destabilization here in the Basque Country, and Catalonia to the south east. The appeal for Basque independentzia, communicated through howls of graffiti and the resurgence of its local (isolated) language Euskara, is a cold steely edge to an otherwise relaxed and city. A frosted edge to a leaf in 34°C. The Guggenheim can bring people to the city, but this venue cannot (and should not) change the nature of the city on its own, nor can a gallery play panacea. The city of Bilbao may not permanently leave its trace upon the Chinese artworks that came to be here temporarily. However, its impact on my understanding of these works will remain; exemplifying the political edge that exists to every seemingly innocuous act, and the equal importance of considering both what is included and what is left out.

Linda Pittwood

Images from top: Sarah Morris’ film Beijing (2008); Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time (1997); Chen Zhen’s Precipitous Parturition (1999); Qiu Zhijie’s Map of Art and China after 1989: Theater of the World. All images from Museo Guggenheim Bilbao, courtesy Linda Pittwood