“Skin and flesh and people desiring each other…” The Big Interview: Jenny Hval

Musician Jenny Hval talks sensuality, criticism, and the porous quality of ideas with Mike Pinnington as her debut novel, Paradise Rot, is released in English for the first time…

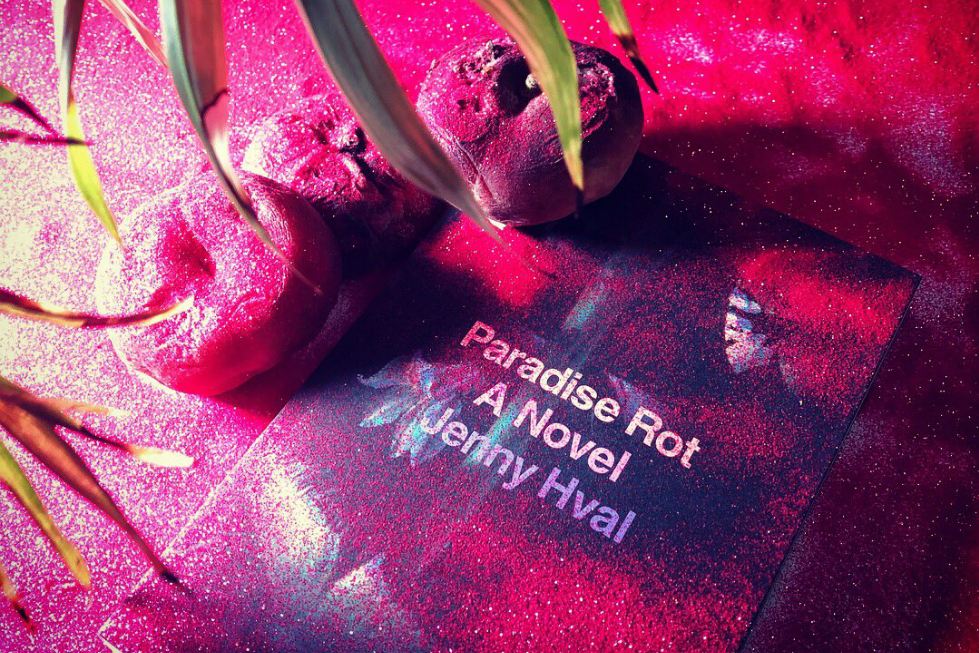

Jenny Hval’s debut novel Paradise Rot (2009) is one of dislocation, different worlds and nascent sexuality. It is populated by encroaching dread and possibility, overripe fruit and fungal protrusions. Its protagonist Jo has just begun university, and has to navigate these treacherous waters.

When I call the Norwegian artist, singer-songwriter and writer Hval, she’s touring a new translation of Paradise Rot with Verso Books. She’s also in the middle of reading.

The Double Negative: What have you been reading lately?

Jenny Hval: I’ve been reading quite a lot, but I was re-reading in English The Hour of the Star, by Clarice Lispector, the Brazilian writer. It’s very beautiful. She’s not an easy read – she’s at war with writing in a way, she’s always in opposition. She’s not comfortable, but she writes beautifully – like mind blowing.

How do you make time for reading alongside being a signed artist and a novelist touring a book?

A lot of writers will do other writing. They’ll be journalists or have other tasks. I tried writing columns for newspapers, but some years ago I just had to stop because I was traveling a lot. I didn’t have the space for so many different types of deadlines.

You have to work very fast and very suddenly – it’s really demanding. I stopped doing that and sometimes I wish I could do more. I really enjoy writing about literature, about stuff I find very interesting. Just exploring through criticism. When you can’t devote the time needed, you’re just doing it a disservice. When you’re playing a show, you’re on stage for an hour. When you’re doing that work, the rest of the day leads up to it, and when it’s done it’s done. And you have the audience there, so it’s very different. It’s really tough to be a critic or a writer.

Did you come to criticism prior to dipping your toe into fiction, or part of the same process?

I got to write for a newspaper after I released my first album in 2006. I started writing some shorter columns about records mainly, but before that I’d studied creative arts, so my dream when I moved back to Norway from Australia, where I’d been studying, was to write very creative essays for women’s journals. My first writing was an article about a German playwright, for this underground theatre magazine, almost like a fanzine; that was the first thing that I got published, so that was my beginning and it tied in nicely with playing more shows and writing music. It made sense to have that parallel brainwork.

What is your process, and do they differ, on the one hand as a songwriter, and a novelist on the other?

I think up until recently it’s definitely connected – I am the same person, but I think I tried to make sense of it being very close, up until the last few years where I’ve enjoyed keeping it separate. I started writing Paradise Rot in 2006, and it was published in 2009. That was very much a process of trying to take my writing in English that was very connected to my song writing. I’d been studying writing only in English, so I felt like I’d forgotten my own language in terms of trying to do something fictional or art related; so that was a really difficult process of trying to relearn language. Trying to reinvent language in a way.

I read that you think of Paradise Rot as beginning as a book but ending up as song lyrics.

I started writing this book in English and it was much closer to how I would perform lyrics – not necessarily song lyrics. It could also be a spoken word piece, something that could be existing in sound. I began writing it as something closer to what I would perform. As I wrote my way through the narrative – the town, the house, the mushrooms – I managed to get closer to something performed, something that’s more musical and I think this is a parallel to the discovery of desire and complexities of sexuality in the work.

How was it received?

People were really disappointed – there was the set up and nothing happens! I didn’t understand, but I think a lot of fiction readers and reviewers would just be so used to a narrative of this or that. I came straight from university when I wrote this book and I was very much in love with a lot of philosophy and a lot of deconstruction, of reinventing language. Just literature and art being very much interested in different forms. Starting with simple narrative and going into to something more complex was a narrative in itself, but I don’t know if that’s clear to the reader.

I came to the book having just read Deborah Levy’s Swimming Home, Crudo by Olivia Laing, and Sarah Hall’s Madame Zero. I was on a good run, and it felt like Paradise Rot was a very complementary read.

I don’t stick to a reading list, I just note things down and I find them again and don’t remember the context. It’s nice to hear about the context, and I also like this idea that you can have this period of reading where the books influence each other, although the writer wouldn’t know this at the time of writing. It’s like creating communities.

How has it been, revisiting the book after so long?

It’s been really strange but also nice. I don’t think I would have revisited it all for a long time if it hadn’t been for Verso wanting to translate it. I think because of the translation, I got to read it in English and revisit it from a distance. That was really nice to go back to it in a different language and be part of pushing it a little bit. I think I got to rethink a few things that I think was improved from my original Norwegian text. Years later I had a thicker skin and I was really ready for some harsh critique and go back and think ‘well this was stupid’! It creates a richer surrounding for the characters, and I think that serves it well.

Did anything surprise you about the book having had time to reflect?

When I published it I was a little lost in the editing that had done. There was a long process of making it more into a novel and I forgot how much there is that is rich, juicy and metaphorical in the world of desire. I was kind of surprised… I’d forgotten there are so many scenes of intimacy. I’d forgotten how close the characters get. I was so interested in the metaphors [when I wrote it] that I’d forgotten I was actually doing something that was brave, and more up front in their sexuality than I’d understood at the time, so I’m kind of happy about that. The description of the book is very up front about sexuality and desire, and I was like ‘oh, I just remember fruit’, but then I reread it and I was ‘oooh, yeah, all those scenes in bed!’.

But it never becomes explicit. It feels tender, almost chaste.

Absolutely, but there is a lot of liquids and a lot of rotting. If you think of the house as body and skin and flesh, there is a lot happening. Almost like a fairy tale. It can be read in different ways: something that is biblical, mythological and almost fairy-tale, that corresponds with a bunch of feminist literature, relating to retelling of metaphors and fairy tales, but it can also be seen as skin and flesh and people desiring each other. I guess that depends on how you interpret the relationship between words, metaphors and bodies. People have this very confusing, very sensory overload phase, where you sort of lose touch with what’s happening – what means what, where you just feel like you’re extending from yourself and you don’t know the limits of things. You don’t know where to draw the lines. Like when you first put on lip stick, it never sticks to your lip-line.

How much of this is autobiographical? How much of you is in Jo?

Well, I think that, I mean everything is about yourself – all characters are yourself. It’s become a natural way of reading things to think that, but I always think I was conscience about not trying to write myself. I took the surroundings and chose to put it in my own time at university, so I would have all these memories of how things worked practically, which is why it happens before everyone has an iPhone, and you read ads for roommates on a wall, which is very weird now.

But I find that all the characters are probably me in a way, and all of them are not. I think I can’t really answer the question too well. I certainly wrote a lot of stuff that I would dream I was like rather than actually be. I remember a very early scene where I think Jo is in the bathroom, and she is seeing her male genitals that are not there, and I thought ‘that’s really cool’. That’s how I see it, I was trying to write myself into someone I was wanting to be. I’m probably all the characters. The writing is an opportunity to go take yourself to places you would never have gone to, but it’s also meeting the reader – like becoming this person that meets people they would never have met.

How do you find the writing works best?

I haven’t been able to write at a steady pace, because I’ve been doing so many other things. I love routine, so I love to have the same writing hours every day, and just work on something. That works really well for me. But I think the most interesting part of the process is when you can free yourself from it and get lost in it. When I can really go into my own thoughts and expand on things, that’s when it’s really happening and that’s when it’s really happening with my music as well. I can like this or that and seem like a cool curator of taste, but at the end of the day, when I write something I really like, it might still sound like a really cheesy ‘80s pop hit that I heard when I was six years old, or at the coffee shop. Something really banal. I’m really just a sponge.

It’s also related to the mushroom and the rotting themes in the book – the thing that sends out spores into the universe, and also how we receive. There’s a porous quality about how we contain art and how we contain our experience.

Like osmosis?

It’s uncontrollable – but I find that if I read too much when I’m towards the end of the creative process, it will just disturb what I’m doing. Like I’m so bored of my own writing, ‘uh, this writing is so much better I need something that sounds like this’. It’s such a great experience to read it, but I find it has nothing to do with where my own work was heading so I cut it like a limb that never really belonged to anybody, so it’s best not to worry too much about where the inspiration comes from.

It’s fine to borrow someone’s voice, you just need a well-digested experience of that voice, to have lived with it for a long time so you know what you’re doing with it, or what it’s doing with you. I find the things I can write about or quote are things that have been living in my brain or my body for a long time. It takes time to quote well or extend well into someone else’s work.

Finally, I was listening to your new E.P., The Long Sleep, and it made me wonder about some of the music you reference, or were listening to when you wrote Paradise Rot.

It’s its own world [The Long Sleep]. In a way that E.P. is not a bad listen along with the book. To me it’s more inward looking and exploratory than a lot of my other work has been the last few years. For me, especially the Long Sleep track, is nice Paradise Rot reading music. It’s probably all connectable.

There could have been a lot more music in the book for sure, but I think that I didn’t necessarily include things I felt strongly about at the time, more things I remember listening to at that age. I didn’t try to make a playlist I thought was cool, more a general student-age experience. I tried to not include things that were more underground to make myself appear more cool. I tried to do the opposite.

Mike Pinnington

See Jenny Hval in conversation with artist and writer Claire Potter on Thursday 25 October 2018, 6.30pm @ The Bluecoat, Liverpool — £5/4

See Hval’s website for more details on the book tour and new E.P.

Jenny Hval, credit Baard Henriksen