“The darkroom is a sacred space…” The Big Interview: Phoebe Kiely

Jacob Charles Wilson discusses abstraction, darkrooms and chancing upon “images everywhere” with BJP Portrait of Britain winner, Phoebe Kiely…

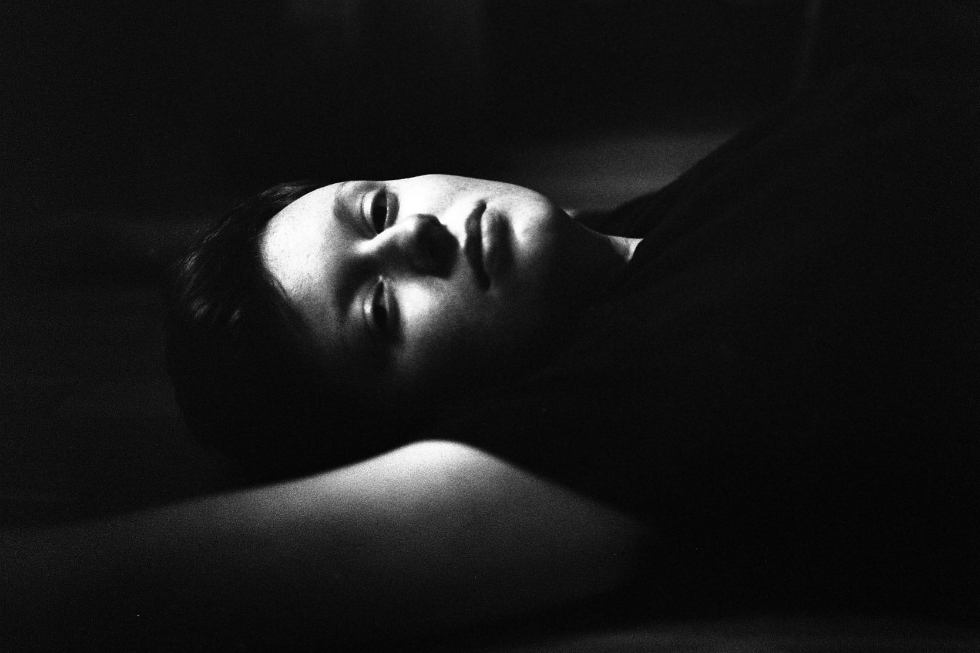

Photographer Phoebe Kiely has an eye for composition and the energy to be constantly searching, producing thousands of exposures on the way. She never limits herself to a single subject but moves, her lens wandering between landscapes, still lives, street portraiture, and abstract scenes. But arriving at the finished piece isn’t simply a matter of taking a picture. Kiely is involved at every stage of the process, she emphasises the importance of the darkroom and treats photographs as objects as much as images.

Her singular vision and craft led to her being named one of the winners of the British Journal of Photography’s Portrait of Britain 2016, and was recently identified as ‘one to watch’ by the magazine. Her work attracted the attention of the prestigious publishers MACK, who earlier this year at Photo London released her photobook They Were My Landscape.

Kiely will be at Open Eye Gallery, Liverpool, this Thursday to talk about They Were My Landscape with the gallery’s curator Thomas Dukes and MACK’s Sooanne Berner. Kiely noted that this event marks the coming together of two organisations that have been instrumental in the past few “whirlwind” years.

Ahead of the talk, I spoke to Kiely to hear more about her unique approach. When I first saw her work I was interested by her use and exploration of the spaces of photography that photography takes place in, the streets and the darkroom, and her movement between them.

The Double Negative: I want to start off by asking where did photography begin for you?

Phoebe Kiely: I studied photography at first at Staffordshire university in 2012 and then transferred for my second year to the Manchester School of Art. I actually took three years out before I studied, and then went to university because I just felt like that was the right thing to do. I don’t know if writing’s the same, but photography’s really hard to get into if you don’t have a degree. There were so many internships, but so many required graduates.

Manchester was good, it put me in touch with Julian Germain and with MACK; [they've] been instrumental in everything really.

Could you tell me about your process? There’s a huge variety of subject matter. You’re not limited to portraiture, you’re not limited to architecture.

Well it’s always really been about carrying my camera everywhere. I think the only times I didn’t carry it was when I knew I was going food shopping because I knew I’d be carrying a lot of bags. Other than that I would carry my camera everywhere because of the possibility that anything could happen.

There’s quite a few images in the book, two that I can think of specifically:a photograph of a man on the floor with blood on his face, and there’s a picture of a window. They were actually taken on the same outing. After a few months of living in Manchester I went to IKEA on the tram, which is actually quite a long ride, and I could see so many things and I wanted to go back. So I bought a day ticket out to Ashton-under-Lyne and got off wherever I could. The window picture I did first, when I got back to Manchester I was actually in Piccadilly Gardens when I saw the man on the floor; I thought to myself ‘this was the reason I was out, this is why I’d left today’, I felt it was really necessary to capture him.

It’s chance a lot of the time. It’s looking. I’m constantly looking. There’s one picture that looks like bin bags, and that was just me going out with my mum in the car to somewhere where she gets eggs. There’s always a chance for images everywhere.

A lot of these are very personal, you mentioned the bin-bag one, and they’re presented without any context and in amongst all these other pictures. How do you expect people will read them?

I don’t know. I think one of the reasons I take them is because something at that time aligns. Whether it’s the light, or the shape, or the person – they’re aligned in that frame before I’ve even got the camera [out]. Something happens that makes me want to take it. I hope that there’s some relevance in what I’m doing, I hope that people seeing those images will see them the way I’m seeing them, and that the organisation within the frame works.

This is one of the very striking things about your work, the formal aspects of it, the composition and the lighting, are very precise. You have a lot of images that tend towards abstraction, such as your photo of the swan with its head underwater…

Is this a style you always had or one you’ve found?

Before I started at university I was shooting on colour film because that was the only thing I could get processed locally. When I started university I knew that I wanted to start shooting black and white, I used 35mm film because that was all I knew. Then in my third year I started shooting on medium format which I was really scared about. I worry because there’s so much more that could go wrong with medium format. But when I look back at the 35mm work, I can see clear links between the work I was making then and the work I’m making now, and there are several years between. I think there are elements there, but the medium format helped me slow down.

I’ve read that the darkroom is one of your favourite parts of the photographic process. Could you tell me what about working in the darkroom it is that you love?

I miss the darkroom. I had the darkrooms at Staffordshire University and Manchester School of Art, which were my favourite spaces, and at Open Eye and the Manchester Darkroom at Artwork Atelier [Salford], which has recently closed. I think the darkroom is a sacred space. It’s so wonderful; the smell, the whole process of going home with all of your prints, it’s the same kind of feeling as coming home with loads of film. I really miss it.

I feel it’s quite balanced between my love of making work in the street and making work physically in the darkroom. It’s different, but it’s really necessary for my practice; the work wouldn’t be the work if I wasn’t making it by hand. The book is a book of prints really; from the beginning Michael Mack was keen to make a book of prints rather than negative scans. I’m really grateful we were able to.Making the physical print is intrinsic to everything. I think my mind, it gets lost and goes into itself in the darkroom.

Where does photography happen? Does it happen when you walk about or when you’re in the darkroom?

I feel like I never edit while I shoot. I just shoot as much as possible, it happens everywhere. If I ever turn to a picture or if I ever see a scene and don’t photograph it, which doesn’t happen very often, then maybe that is me editing the work. Me editing in the reel doesn’t happen very often. It happens in my head without a camera, before I even pick up a camera.

So many photographers are keen at emphasising they were there in a moment, and they never talk about using a darkroom, they rarely talk about editing, but in your work you’re shooting a massive amount, which is all coming together in the aftermath.

It’s the way I’ve always worked, I think it’s quite unusual to think of being a photographer and not editing. I experienced it at university, people made photographs on certain themes and needed to structure their work in a certain way, but I didn’t fit into that way of working. I remember Julian Germain saying that I’d figured out a way to make a lot of work. I think I had to construct a way of working different to what other people do. If I had done what they do I wouldn’t make half as much work. The way that I do work it allows me to just keep going.

Speaking of keeping going, what plans do you have?

I recently quit my job and I’m going travelling. I want to experience the world but I want to photograph the world, that’s the whole point of the trip really. Since photography has been my all, I haven’t been abroad. So I think this trip is going to change things a bit, the work is going to change, it’s not going to be Britain.

I was always worried about the next stage, and I am at that point again, now the book’s out. I love the book, I’m very happy about the whole thing that was done – it’s so incredible. But I think I’ll never stop worrying about the next thing. I think if I ever do, that’ll probably be a bad thing. I’ve always felt that I need to keep momentum, and that’s kind of scary.

Jacob Charles Wilson

See Phoebe Kiely in conversation with Thomas Dukes (Curator) and Sooanne Berner (MACK books) on Thursday 23 August 2018, 6-7.30pm, at Open Eye Gallery — FREE

See more on the artist’s website phoebekiely.com

All images courtesy Phoebe Kiely, They were my landscape (top image, detail)