A Tale Of Two Dystopias: Sam Meech’s Apocalypse In Barrow And Manchester

Imagine, in 1000 years time, if fidget spinners were the only surviving relics of human civilisation? Artist Sam Meech imagines a post-digital future inspired by apocalyptic fiction and lost industries, finds Joe Fenn…

As the setting for an exhibition about the apocalypse, Sam Meech could hardly have chosen a better location. Barrow-in-Furness is a small, isolated city on an isolated peninsula on the Cumbrian coast; the last stop on a remote train line, cut off from the world on either side by the foreboding waters of Morecambe Bay and the Irish Sea. The main business since the iron and steel-works disappeared last century has been the building of Trident nuclear submarines in the old shipyards. And on that cold November exhibition opening night, the ink black sky had poured Biblical rain down for days, blocking roads and railways and cutting off both the wider world and potential visitors.

But for those who could make it, it was here, in the local train station, that Meech announced his dystopia to the public with the haunting tones of an ominous musical round sung by some 20 Barrovian schoolchildren. His first of a brace of shows in Barrow and then Manchester, Time Back Way Back was an image of a post-apocalyptic future cast in concrete, inspired by Russel Hoban’s dystopian 1980 novel Riddley Walker and Signal Film and Media’s 2017 Lost Stations programme, a year-long study on the region’s lost industry.

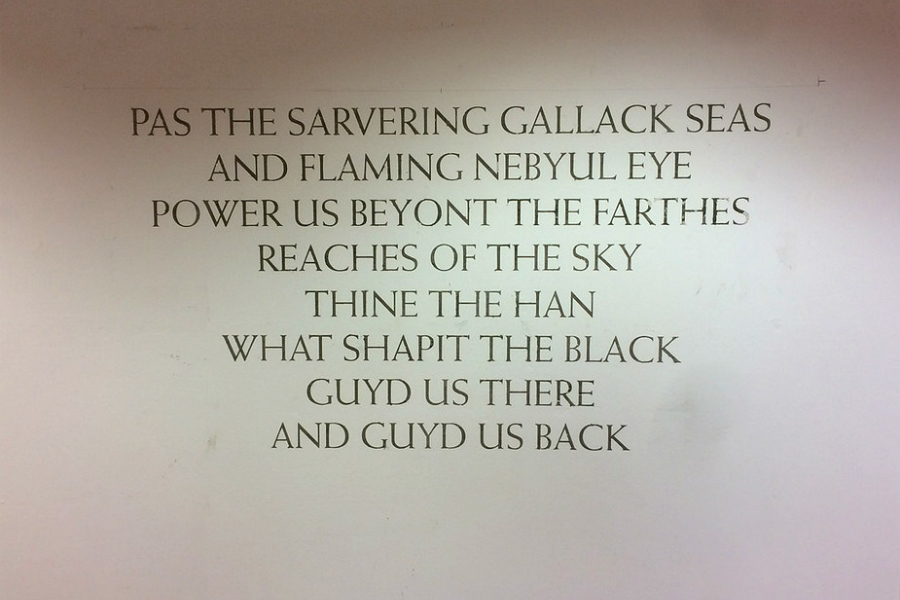

Across the road, the audience was given a disconcerting hammer and respirator and turned loose into a dark, bare-brick room. Strange words, lifted from the decayed, post-apocalyptic dialect in which Riddley Walker is written and writ large across the room and pieces, struck one immediately on entering; two concrete gravestones stood along one wall, lamenting obscurely of “Oh What We Ben! / And What We Come To!”. Myriad artefacts cast in concrete littered the floor, from a child’s train set, to Autumn leaves more usually ephemeral, to, at one end of the hall, a great concrete circle inviting our hammer blows. Encased within is a cast-iron, 95-pound fidget spinner.

The dark, the dirty and dusty quality of the concrete, and the esoteric yet discernibly ominous language convincingly immersed the audience into the confusion and panic of a disaster scenario. What Meech describes as his “concrete Pompeii” is a reflection on transience and permanence, the contrasting safety and complete vulnerability of different elements of human produce.

A multimedia arts graduate, Meech works across a spectrum of materials, but it was his early work in the digital realm which highlighted the precarious nature of much modern human work in our digital age. Most would recognise the concern. Anyone who has had a computer crash at an inopportune moment will know well how hard-wrangled work can disappear into the binary void without the slightest whimper. It is, as Meech describes it, the flip side of the ease of working with digital media; they are equally easy to work and easy to lose.

But more than a matter of a lost document or two, as more and more of human produce and society moves onto computers and the internet, the question confronting Meech became ‘what would the post-apocalyptic future of our digital present look like?’ What of our society would survive an apocalypse, if digital data did not? What would be our artefacts, and what would a future society built on those artefacts look like?

Hence the fidget spinner. If an apocalypse were to strike our modern, digital world, it is very possible that our most important cultural landmarks – the internet, digital archives, the data from decades of scientific research – would be destroyed with little trace. But what would survive is the millions of frivolities we have produced in a material that is essentially indestructible. If nuclear warfare were to destroy our society, it would be more from the remains of plastic forks and lighters, rather than our digital produce, that future generations will draw their picture of us. Casting one of these items in iron – a material we, wrongly enough, think of as much more permanent than plastic – prompts uncomfortable reflection upon our relation to physical materials and our environment.

But while a world carpeted in plastic may dominate our visions of the future, and all too realistically so, the foundations of Time Back Way Back are lain in concrete. A remarkable material with a history and lifetime which stretches into the thousands of years, concrete is one of the truly ubiquitous building blocks of modern human settlements, prone to persisting long after the societies which lay it have crumbled. Roman concrete cast two millennia ago stands strong to this day; the concrete in the Hoover Dam will not dry for a hundred years and is predicted to stand for 10,000. Versatile as well, practically every piece in Meech’s show features the grey stuff, from the artefacts to the words written on the walls with concrete dust. Even the word itself has become synonymous with permanence; as a choice of material for a study of our legacy, few could be better. And the workmanship in Meech’s castings is obvious.

Not concerned solely with the physical, our cultural legacy is also under scrutiny, not merely through comment on the fad of the fidget spinner, but also using language. Indeed, before one has even set foot in the space, the strange phrasing of the title, Time Back Way Back, pleasant but catching on the ear, piques interest. Meech uses the dialect developed in Hoban’s book, a masterpiece of literary creation, and well worth the read, to investigate the way in which cultures and their practises would also decay, develop and evolve following an apocalypse. Hoban provides a convincing conception of what written language would become in a post-literary, almost post-literate world, and Meech makes good use of this.

It is also the connection to Hoban which carried Meech’s work to the Anthony Burgess Foundation. As a fellow linguist and novelist, Burgess was an avid fan of Hoban’s, and Riddley Walker in particular; describing the novel as “what literature is meant to be.” Thus, several months after that dark night in Barrow, several of Meech’s pieces, along with some new, and some from the Foundation’s archive, could be found at his second show, Girt Shyning Weals.

But despite being constructed from mostly the same pieces, the differences between the two shows are more striking than the similarities. Where Time Back Way Back had the dark and chaotic feel of a disastrous future, Girt Shyning Weals had the bright, sterilised feel of a museum. Glass cabinets held books like specimens. The great fidget spinner lay prostrate and uncovered on floor like an artefact. Even those ominous graves are less striking in the bright lights.

Initially a cause of concern for Meech, the different atmospheres in fact provide two brilliantly different vantage points into his world. In Barrow, the audience is emerged into the artist’s dystopia as someone trapped within it. In Manchester, we look upon the artefacts we saw in Barrow like we do those from the ancient world. The atmospheres also reflect their cities well, and their luck in the march of the digital age and modernisation; Barrow, the deprived and forlorn town which keeps itself alive building the end of the world; Manchester, the slick, pulsating modern city, full of the bright lights and space age technology of the 21st century and all the wonders and horrors that go with them.

Meech’s world met its own apocalypse just last week at its end-of-the-world closing party, billed as 1big1, the name used by Riddley Walker and his contemporaries for the event that ruined their world before they ever inherited it. The Burgess Foundation’s event space is much more like Signal’s space, bare-brick and dark. Drinks were followed by a partial screening of the truly bleak, banned-for-years nuclear television drama Threads (1984), before local opera and drama company Opera Shack sang a truly beautiful dramatic medley. Ending as we started, with melancholy song on a dark night, one is reminded of the repetitive nature of human endeavour; the circles which so obsess Riddley’s society. And the thought that the only thing which would stop that circle would, more likely than not, leave us much worse off than we are now.

Joe Fenn

See Sam Meech’s GIRT SHYNING WEALS until Friday 20 April 2018 at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation, Manchester — FREE

Gallery open 10am-3pm weekdays and in the evenings and at weekends during events

Joe saw Time Back Way Back on 23 November 2017 at Barrow Station and Cooke’s Studios, Cumbria, where the exhibition continued until 9 December 2017