“The concept of revolution is ubiquitous and urgent”: What’s Left? A Century In Revolution

What’s Left? A Century in Revolution at Tyneside Cinema Newcastle marks the centenary of the 1917 October Revolution in Russia. Mike Pinnington interviews programme curator Úna Henry to find out how the films examine global movements from then until now, to consider the significance of the term “revolution”, as well as the impact of revolutionary events today…

The Double Negative: How did you first become involved with the project and with the Chto Delat? collective?

Una Henry: In 2011, I curated the statement exhibition, What Is To Be Done Between Tragedy And Farce?, with Chto Delat? at SMART Project Space in Amsterdam. Interlacing a humanising pedagogy to social struggle with the representation of historicity within Russian culture, they developed a complex programme on the performative nature of agency and knowledge acquisition as a way to act in and shape the world, dramatised through installations, lectures, film screenings, a newspaper, reading room and participatory workshops (such as The Shop of Utopian Clothes) and produced a new film commission, The Netherlands 20XX, with the van Abbemuseum. Chto Delat? were present in Amsterdam throughout the entire duration of the exhibition. It was a distinctive experience, working together on turning the institution into a platform for discourse, research and debate.

When I was approached to curate a public programme in Newcastle with Durham University celebrating the Russian Revolution that examines the historical and political vicissitudes of the revolutions as such, to the potentiality of movements today, there could not be a more timely moment to involve Chto Delat? in tracing the conceptual and historical nuances of revolution and the new imperialism of the Russian contemporary context.

The question in the title, What’s Left?, feels eerily applicable to today, was that intentional?

A thoughtful but forbidding nod. Today’s new global expansion of capitalist relations is similar to the sixteenth century processes of primitive accumulation and the attack on what is ‘commonly held’ today. Take by way of example the World Bank’s international monetary fund that has assisted countries such as Nigeria to enter into the world market, a process in which commonly held lands have been destroyed and peoples right to water denied. The illth of enclosure is the expropriated land from millions of subsistence farmers leading to paramount pauperisation of workers and the criminalisation and persecution of the migrant that we see today. At the same time the World Bank inserted a policy known as the “War Against Indiscipline” that not only reproduces labour exploitation; it is a germane intervention aimed at pulling community bonds apart through the separation of production from reproduction, leaving in its wake a dramatic reproductive crisis that subsumes the whole area of personal relations.

Alongside expropriation, the foundational process of primitive accumulation, as analysed by Marx, revealed a new type of person, the individual, utterly displaced from their natural social bonds, and it marked a new type of worker, the proletariat. Today there are more proletarians on the face of the earth than ever before in history; a mass, termed by Hardt and Negri as the “multitude”. Today there are more and more demands being made by the multitude to share wealth and this has given way to grassroots organisations and movements of “actual autonomous communism”, communing to safeguard common resources.

Throughout the 1990’s the socialist illusions of much of the left crumbled along the wayside with the apparent defeat of communism. This gave big power diplomacy of the ideological right an open clearing to make a secure advance. However, the so-called fall of communism on the one hand, and the global movement that started with the struggles of the Zapatistas in Mexico to “reclaim the commons” on the other, has put the issue of the commons back on the agenda, rupturing out into other arenas as vigilant movements to safeguard the rights and liberties of people.

What is it about revolution that so fascinates, and why do you think revolutionary figures are often fetishized and portrayed in romantic ways?

In its various contemporary manifestations, the concept of revolution is ubiquitous and urgent. There is so much to learn from the history of revolution and to its possibility. October brought us a fleeting moment, a transition from injustice to emancipation, a flash of light in the night, where workers had control over their production, and equal rights for men and women, not only in work but also in marriage, homosexuality was decriminalised and universal education was free.

However, the fetishising of the often-patriarchal classical revolutionary figure is controversial.

How were the films chosen?

The film’s that I’ve chosen map connections and constellations between different times and places (China, Syria, Ukraine, Cuba), starting in 1917 Russia moving through the century to the potentiality of movements today. The programme is organised around several critical issues (gender, technology, nationhood, migration), under thematics such as Changing of the Guard: Revolution Across Generations, Beyond the Political: Cinema of the Real, In the Hands of Millennials: Technologies of Revolution, and Women on the Frontlines: Gender in Revolution, the latter by way of example taking note that it was the women’s protest in Petrograd in 1917 that sparked the revolution leading to the overthrow of the Tsar. During the Arab uprisings in 2011, women took to the streets beside men. But as the elation of revolution gave way to the long-winded process of governing — and often the chaos and in the wake of war — women disappeared from the narrative of resistance and the revolutionary paradigm. I show that behind the scenes, women continue to play vital roles in the transformation of their society.

What can the films and the programme more broadly tell us about the world we inhabit now?

The Russian imperial past is of such importance and the vector points of fascism, new imperialism and austerity can be garnered through this. As a start towards thinking about the potential of cultural power within a transformative social movement (with reference to early avant-garde rhetoric and following through) the film by Sergei Loznitsa The Event (2015), also Harun Farocki’s Videograms of a Revolution (1992) and Chto Delat?’s new film on the Zapatistas portray a powerful statement of resistance to the current order and are a defense to individual realities thwarted by the naked violence of the state and dominant histories. In spite of the dystopian black hole that we are living in, where institutions show little regard for the plight of human suffering, the films show actualities on the ground, the prudent and courageous acts of resistance taking place across the globe and the intensification of revolutionary politics today. Theoretically people resist because of injustice, and seeing others suffering that becomes intolerable.

If people could only make one screening, what should it be and why?

There is no easy choice. All films are worth seeing, each showing the different shapes and textures that “leads to” and “is of” revolution, elucidating, critiquing and defying political oppression.

In 1917, Lenin said that “Art is the most powerful means of political propaganda”. Do you agree with the statement, and how is the world of the moving image bound up with that?

Art is a vital tool, but it is also a fetishized commodity, so we must be careful to separate the two. We need to move beyond this statement and give it an extra dimension that holds more sway, John Roberts writes, “… for in its heteronomous encounter with capital, art must offer a place, a memory, a set of relations, modes of cognition and learning and mapping, that provides a different space of encounter between praxis, critique and truth – a place that sustains an open and reflective encounter between art and the totalizing critique of capitalism”.

Revolutions are generally expected to happen ‘somewhere else’ by those in the West. Are we reaching a point when that isn’t necessarily any longer the case?

We are living in a newly revolutionary age. Revolts as we see across the globe today are connected with wider circuits of social dissent that draw a line from the Zapatista uprising in 1994, the Battle for Seattle protests in 1999 that ran on to Genoa, and were continued in struggles during the Occupation movements of 2009 and 2010 in wide parts of Europe and the US.

For all its perils, revolution possesses its own persistent discourse. Its affinities abide not only with the unhappy trajectories of repression and war that happen “elsewhere”. We can argue however that the economic philosophy of neoliberalism is no longer able to constitute itself as a viable system. Many are suffering in abjection. So perhaps we are moving closer to a call to action through the poor’s suffering against poverty, while the government represses opposition to the structural inequality of our times, killing the notion of the democratic process and is a tool for silencing resistance of the “constitutionally ignorant”, and the belief in the inferiority of their intelligence. To this end, contemporary capitalism is in a state of crisis. This is further enhanced by the fact that we are living in a poisonous political moment that suggests something terrible about our culture.

Rather than apocalyptic despair at this conjecture, I have hope that there is a horizon beyond for a better world. The time of revolution and transformation is possible. There is the potentiality for autonomous organisation that breaks with capitalist capture, subversively questioning the status quo in the context of today’s dominant culture and its symptoms: the increasing gulf between rich and poor, corporate theft of communally held lands and the commons, ecological devastation and the cumulative effects of new class struggles. October 1917 is the epochal event of the century to be approached as political inspiration. Might history repeat itself, first as tragedy then as farce? I am cautious.

Chris Marker was exploring the crisis of the political left with his 1977 film A Grin Without a Cat. What would he make of the political landscape of 2017?

Chris Marker may think “as it always was, again and again and again”, signs of the continuous revolution. However, in 1989 we broke with the epoch of revolutions and today’s revolutionary paradigm is one of a politics of resistance. Our present phase of capitalist globalisation presents phenomena associated with primitive accumulation; seen in the world wide return and intensification of violence, expropriation of millions of agricultural producers from their lands, phenomenal plundering of natural resources, the ravages of war, persecution of migrant workers and the continued degradation of women and requires the sustained theory and practice of resistance that stood at the margins of revolution that inspired Chris Marker, doyen of the non-fiction film essay.

Mike Pinnington

See What’s Left? A Century in Revolution — including A Grin Without A Cat (1977) and My Father’s Choice (2017) — until 8 October 2017 at Tyneside Cinema Newcastle

Ticket prices from £6.75—FREE; pass for five films in season, £25; pass for three films in season, £18

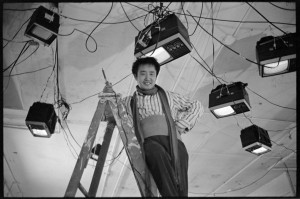

Stills, from top: Yan Ting Yuen’s My Father’s Choice (2017); Sergei Loznitsa The Event (2015); Harun Farocki’s Videograms of a Revolution (1992); Chto Delat?’s new film on the Zapatistas; Chris Marker’s A Grin Without A Cat (1977)