Me, Replicant? The Cultural Impact Of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982)

How can Denis Villeneuve’s new Blade Runner 2049 live up to Ridley Scott’s original? A film that took Philip K Dick’s famous source novel, and went on to spawn its own mythology, as well as shape science fiction in its wake — including Cyberpunk and Black Mirror? C. James Fagan takes a nostalgic look back at the 1982 film and its sprawling, heady impact…

Me, Replicant?

You’ve probably noticed that the long awaited sequel to Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) has been released. Blade Runner 2049 has long been wished for, and what do they say about getting what you wish for? I’ve never had a mixture of excitement and nervousness like this in anticipation of a film. Not even the new Star Wars.

Despite having confidence in Oscar-winning director Denis Villeneuve (Arrival), I — unfairly perhaps — have already formed an opinion of Blade Runner 2049; in that it will be a good film, but it won’t be Scott’s Blade Runner. How can it be?

It’s got a lot going in its favour: Villeneuve, its BAFTA-winning cinematographer Roger Deakins (James Bond, Coen Brothers), and, until recently, its composer Johan Johansson (who collaborated with Villeneuve on Arrival and two other films). Johansson and his score have been replaced last minute by score veteran Hans Zimmer (Inception, The Lion King), which sets off alarm bells – the director being quoted in IndieWire as saying: “I needed to go back to something closer to [Blade Runner’s original composer] Vangelis. Jóhan and I decided that I will need to go in another direction”.

My misgivings may also spring from the fact that any Blade Runner follow up comes with a major disadvantage: it doesn’t have the mythos of the parent film. Not only does Villeneuve have to contend with Scott’s influence on the original, but also the series of conceptual symbols that he wove throughout the original (eyes, looking, owls, etc.) and are now so synonymous with the film. Plus, there’s Scott’s core narrative of whether the main character is human or Replicant, and the gossipy production mythology – stories of on-set rivalries, tensions, and various edits which remain firmly fixed in the minds of its fans.

I know it’s common for sequels to fail to match the original, but Blade Runner isn’t just a film. The influence Blade Runner had on subsequent films could be classed as a genre in itself. It’s one of four works which marked a shift in the idea of how science fiction could be presented on screen: Star Wars (1977-present), Alien (1979-present), Mad Max: Road Warrior (1981) and Blade Runner. Of course, these films didn’t spring from a vacuum. Each of the production teams were influenced by popular culture — samurai films, French comics and weird Swiss artists – taking elements from different sources and putting them together in a way which stirred the imagination. To create worlds which recreate the effect and sensation the likes of Ridley Scott experienced when viewing that original material for the first time.

Blade Runner’s entrance into my imagination happened at an early age, while I was still at primary school. Though it wasn’t with the actual film, rather it was with a publicity still in a magazine given away free when you hired a video. The image was of one of Los Angeles’ rain sodden streets in 2019. In the foreground was parked a strange looking car. The car, which I would later learn was one of Syd Mead’s designs, was somewhere between exotic and ordinary. Something that was recognisably a car, but one that was as exciting as a Lamborghini Countach, and yet as familiar as an Austin Princess.

Looking back, Blade Runner drew you into its future-set world by drawing, in turn, from the familiar and recognisable. A lot of the look and feel of Blade Runner came from Scott’s experiences of growing up in the North-East of Post-War Britain. Blade Runner’s opening scenes featured a landscape completely colonized by industry, and was, in part, a homage to the refineries Scott saw on walking to and from art school. This imagery struck a deep chord with me, and many others; growing up in Runcorn I was familiar with the ethereal beauty of chemical refineries of ICI and BoC at night — complete with flaming towers.

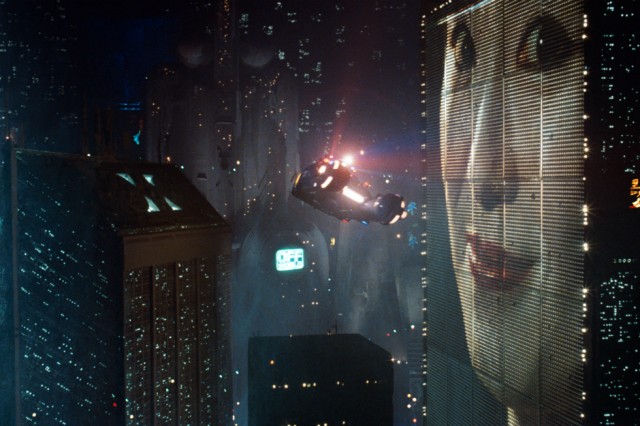

It’s this stark imagery, coupled with Scott’s insistence on details, which goes to create a living, breathing world. The city serves as another character in the film. The sensation that you can leave the main characters and explore the city is palatable. Maybe have some noodles or a drink at Taffy’s Bar. It’s this level of detail which makes Blade Runner a high water mark for film design. It fixed an idea of the future in the popular imagination that still has a hold. It has informed the visual style of many a future world to varying degrees of success. It inspired a series of bank adverts.

Blade Runner even effected future Philip K Dick adaptions and book covers; a recent radio adaption of the author’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) — the source novel for Blade Runner — took its cues from the film, presenting the hero as a gruff private eye like Scott’s adaptation, rather than the dweeby admin assistant of the book. Ironically, the first episode of Philip K Dick’s Electric Dreams TV series drew criticism for being a cross between Blade Runner and Black Mirror.

It just goes to show how powerful the visuals of Blade Runner have been; how much it chimed, and still does, with the times. Through it, you can see an expression of the concerns of the time: global war, pollution, over-population, and industrialisation. It was part of the zeitgeist, and it defined the zeitgeist. Blade Runner become a blueprint, if indirectly, for the Cyberpunk genre. Even though author William Gibson was already in the process of writing the Neuromancer novel (released 1984), the visual style of Blade Runner was an easy fit for the world of The Sprawl: his huge urban sprawl development that spawned a trilogy. That Blade Runner aesthetic had already become a shorthand for the meeting between low life and high tech. And technology would have a hand in projecting the Blade Runner mythos.

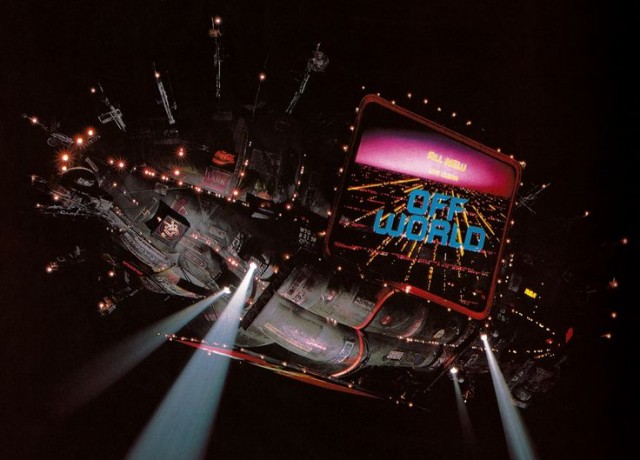

After originally failing at the box office, Blade Runner found an audience with the newly emerging home video market. Here, you could gain access to 2019, if very crudely. By rewinding and pausing, you could engross yourself in that world, making Blade Runner something other than a movie. Directors Cut in 1992, Fans would spend hours decoding Cityspeak (the film’s street language), trying to discover what that music drifting from the blimp was, or the brand of cigarettes smoked by everyone.

Of course, they would learn that the version of Blade Runner they’d seen wasn’t the Blade Runner Ridley Scott intended you to see. News of a fabled “workprint” came to the surface: versions without Harrison Ford’s bored narration, and a radically different ending. Eventually, this would be released as the Directors Cut in 1992, though a Final Cut wouldn’t be released until 2009. There are seven different versions of Blade Runner in all.

It shows that this thing we call Blade Runner is more than a movie: it is part of contemporary culture. This is what Blade Runner 2049 is up against. 35 years of myths, 35 years of influence. Villeneuve is an ambitious director to want to enter that world. But if anyone could make a successful attempt at becoming part of that mythos, it could be him. After all, this isn’t and shouldn’t be about me and my like reliving the sensations of watching Blade Runner. It’s about ensuring that the Blade Runner myth can live long beyond its inception date and inspire a new generation. Given the very positive reviews already filtering through, that maybe the case. It won’t be long until we can all get down to the cinema and see for ourselves. Until then, have a better one!

C. James Fagan — from an appropriately rainy city

See Blade Runner 2049 at cinemas nationwide

Images, from top: a still from Denis Villeneuve’s new Blade Runner 2019, and in contrast, a similar scene from Ridley Scott’s Final Cut of Blade Runner in 2009. One of Syd Mead’s original designs from Blade Runner (1982). A still from Ridley Scott’s Director’s Cut of Blade Runner in 1992. Blimp, from Blade Runner (1982)