“Set fire to the library shelves!” In Profile: Futurism And The Birth Of The Artists’ Manifesto

As Cate Blanchett takes the lead in Julian Rosefeldt’s new film Manifesto, we take a look behind the thrilling art movement that aimed to shake up early 20th century Italy by publishing the very first artists’ manifesto. Yet Futurism, as it became known, was doomed to end in violence, death and fascism…

“Our hearts feel no weariness, for they feed on fire, on hatred, and on speed!”

The Futurists wrote the best artists’ manifestos. In fact, they created the trend: their inaugural statement, entitled The Foundation And Manifesto Of Futurism, was written and championed by the movement’s charismatic figurehead, Filippo Tommaso Emilio Marinetti, in 1909. A seminal text, it not only inspired the artists’ manifesto as we know it today, but also spawned at least 27 more evolving Futurist manifestos, which defined what its supporters thought the movement stood for: declaring opinions on everything from painting styles, lust, food, and architecture. The 1909 manifesto also quickly encouraged followers of other art movements to write their own; before Marinetti’s death in 1944, hundreds of artists from France to Japan had co-signed manifestos outlining Rayonism, Suprematism, Dadaism, Constructivism, Surrealism, Dimensionism, and Concrete Art.

But what was Futurism? Simply put, it was the first movement of the avant-garde; obsessed with new ideas, its Italian associates intended to shock a dormant public into action. The Futurists thought that Italy was falling behind the rest of Europe, and were frustrated at a perceived stagnancy. In politics, long-serving Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti was considered to be either too liberal or too corrupt (he who courted unions, was an advocate of universal male suffrage, and was impeached for abuse of power). Nationalism was on the rise, after neighbouring territory disputes in preceding years (the Bosnian crisis and the First Moroccan Crisis). The intellectual and creative advancements of the Renaissance – pioneered by Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and Tintoretto – and during the Baroque period – Caracci, Caravaggio – were considered by Futurists to be stale; at worst, as dead heritage holding the country back from new artistic growth.

In response, Marinetti – a philosopher, novelist, playwright and propagandist – wanted to tear down and destroy all the old traditions. Quite literally, in fact; included in his hot-blooded manifesto of 1909, which was published on the front page of Italy’s largest newspaper Le Figaro in the February, was a call to “to smash down the mysterious doors of the Impossible” and “destroy museums, libraries, academies of any sort”:

“So let them come, the happy-go-lucky fire-raisers with their blackened fingers! Here they come! Here they come!… Come on then! Set fire to the library shelves! Divert the canals so they can flood the museums!… Oh, what a pleasure it is to see those revered old canvases, washed out and tattered, drifting away in the water!… Grab your picks and your axes and your hammers and then demolish, pitilessly demolish, all venerated cities!”

Other key (male) Futurists and manifesto co-signatories included painters Umberto Boccioni (whose own manifesto followed the year after in 1910, entitled Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto), Giacomo Balla (author of Futurist Manifesto of Men’s Clothing, 1913, and who, dedicated to the cause, named his daughters Propeller and Light), Carlo Carra (The Painting of Sounds, Noises and Smells, 1913), Gino Severini, and Luigi Russolo, who was also an experimental composer (his 1913 manifesto The Art of Noises arguably invented noise music, a genre that gained huge popularity in the 1970s). This young, ambitious cohort (“The oldest among us are thirty”, they declared) professed a great admiration for modern tools that would revolutionise the artist’s toolkit: namely motion capture, time-lapse photography and early cinematic processes.

The dynamism of scientist Étienne-Jules Marey’s early animations, like L’ Homme Machine (1885), can be seen to have clearly influenced Balla’s paintings Dynamism of A Dog on a Leash (pictured, top) and A Young Girl Running on a Balcony (both 1912); their legs appearing in sequence, and in the dog’s case, suggesting the blurry transitions in between movements. Boccioni’s bronze sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913, pictured above) is another famous example, depicting an imposing male figure striding towards progress, his legs leaving behind a trail of flaming, abstract shapes.

This obsession with technology extended to that traditionally male pursuit: fast cars. The first American automobile race had been held in 1895, France had started numerous clubs and races, and the first purpose-built motor racing venue had opened in the UK in 1907. Racing cars were alluring, sexy, and futuristic:

“We believe that this wonderful world has been further enriched by a new beauty, the beauty of speed. A racing car, its bonnet decked with exhaust pipes like serpents with galvanic breath… a roaring motor car, which seems to race on machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Winged Victory of Samothrace.”

Again portraying movement with brushstrokes, Balla’s Abstract Speed – The Car has Passed (1913, pictured above) blurs land and sky as the vehicle accelerates along a country road; while Severini’s Suburban Train Arriving in Paris (1915) roars past houses and roads, leaving huge clouds of steam in its wake, as alive and hungry as a great beast.

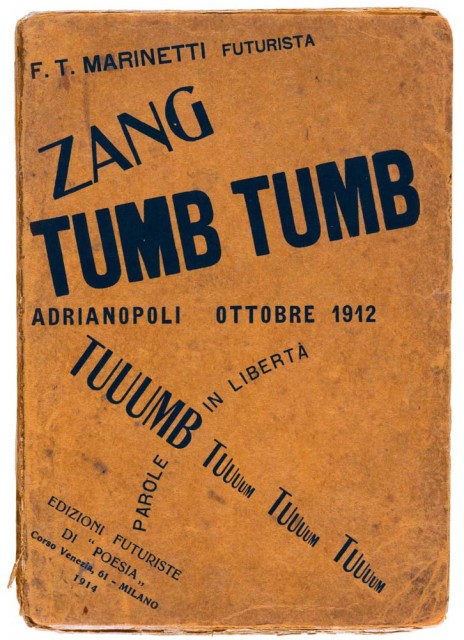

No wonder that Futurism, and Marinetti’s “poetry of the revolution”, was so enthralling. The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism was nothing short of a call to arms; modelled on Marx’s Communist Manifesto (1848), with added verve and youth appeal, it was touted around music halls and theatres across Europe by enthusiastic Futurists. Instantly recognisable today, their signature style of visual poetry, called “words in freedom” (pictured, below), were printed and read aloud at chaotic evenings as live art and performance, accompanied by music and heated discussion. These meet-ups regularly ended in riots with local police. Futurism had spawned a masochistic manifesto that revelled in art as annihilation:

“Art, indeed, can be nothing but violence, cruelty and injustice.”

Thus, it is with a certain irony that Futurism’s decline began with global war. In May 1915, Italy revoked the Triple Alliance and declared war on Austria-Hungary, officially joining World War I. The Futurists actively campaigned for Italian involvement. Just six years before, their Foundation And Manifesto Of Futurism had declared:

“We wish to glorify war – the sole cleanser of the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive act of the libertarian, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for women.”

Their wish was granted. Futurists created propaganda for the allies, made speeches, and wrote pro-war articles and words-in-freedom from the trenches. Marinetti, Boccioni, Russolo, and other Futurists volunteered for service not as fighter aircraft pilots or machine gunners – the cutting-edge of modern machine warfare – but more fittingly as racing car fans, for the Lombard Battalion of Volunteer Cyclists and Motorists. In retrospect, it seems a curiously sentimental choice for such fierce advocates of new technology, yet was no doubt led by a romantic notion of combat, rooted in nationalism.

The reality was, of course, acutely different. Now known as one of the deadliest wars in human history, military and civilian casualties totalled more than 41 million. Italy alone lost 2.96% to 3.49% of its population, Boccioni included, who was perhaps the most famous Futurist fatality of WWI. Joining an artillery regiment at Sorte of Chievo in May 1916, he was dead just three months later after his horse was frightened by a lorry. Thrown to the ground and dragged, 33-year old Boccioni died from his injuries the next day.

It was a cruel death, not only due to the mundanity of the accident, but also the irony of its cause: a vehicle. Even stranger, Boccioni seemingly forecast his own death in his one and only war work, The Charge of The Lancers (1915, pictured below). A painting over collaged newspapers, horses appear to symbolise military strength, kicking back against German, man-made bayonets.

Other Futurists survived, like Balla, whose studio became a meeting place for emerging artists throughout the war, and who diversified his practice into sculpture, design and fashion. Severini painted three notable works in 1915, entitled War, Armored Train, and Red Cross Train, yet left Futurism behind in 1916, turning to Cubism. Carrà also moved away from Futurism. Writing the Warpainting manifesto in 1915 – in which he outlined a preference for “dynamic distortion in painting… used to fight any tendency towards the ‘pretty’” – he proceeded to depict still forms and landscapes.

Marinetti, however, continued to be Futurism’s trailblazer. Seriously wounded on the Isonzo front in 1916, he recovered enough to fight for Italian victory at Vittorio Veneto in 1918. However it was in an armoured tank rather than bicycle, that he liked to call his “steel alcove” and “mistress”. That same year, Marinetti founded the Futurist Political Party, which merged with Benito Mussolini’s The Italian Fasci of Combat in 1919, making Marinetti one of the founding members of the Italian Fascist Party. Marinetti continued to use Futurism as a platform on which to call for societal and political change. Co-writing the fascist manifesto, published in the Il Popolo d’Italia newspaper in in June 1919, it made many demands, including the abolition of the Italian Senate, and ones which seem surprisingly liberal from contemporary perspectives, including universal suffrage for both men and women and the creation of a minimum wage for all workers. Audacious and contradictory until the end, he declared himself both an atheist and a Catholic; an academician who hated academic institutions; and a fascist who protested publicly against anti-Semitism. It was Marinetti who asked Mussolini to prevent Adolf Hitler’s degenerate art exhibition from coming to Italy, as it dared to include Futurism.

His final artist manifesto remains entertaining, and expressively sums up Futurism for a new generation. Published in two newspapers in 1930, it was also used to advertise first Futurist restaurant that opened in Turin, 1931, plus the Futurist cookbook of 1932. The Manifesto of Futurist Cuisine was “against pasta” and other classic Italian foods:

“Contrary to established practice therefore, we Futurists disregard the example and cautiousness of tradition so that, at all costs, we can invent something new, even though it may be judged by all as madness.”

Laura Robertson, Editor

See director Julian Rosefeldt’s new film Manifesto (2017), starring actress Cate Blanchett, at venues nationwide now

Further reading: 100 Artists’ Manifestos: From the Futurists to the Stuckists, Alex Danchev, Penguin Classics. Published 2011

FuturBalla: Life, Light, Speed, published in 2016 by SKIRA, Italy, and distributed in the UK by Thames & Hudson

Images, from top: Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash, Giacomo Balla, 1912, Italy; oil, canvas; 110 x 91 cm; Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY, US; courtesy Wikiart. Umberto Boccioni, Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, 1913, cast 1972; image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported), published on Tate. Abstract Speed – The Car has Passed 1913 Giacomo Balla 1871-1958; presented by the Friends of the Tate Gallery 1970 © DACS, 2017. Cover of Zang tumb tumb: Adrianpole, October 1912: Words in freedom © 2013 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Rome; photo The Museum of Modern Art, Imaging and Visual Resources Department. The Charge of the Lancers, Umberto Boccioni, 1915; Milan, Italy; collage, cardboard, tempera; 32 x 50 cm; Private Collection; courtesy Wikiart