Field Trip: Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina

Bob Dickinson takes a detailed tour of Bosnia Herzegovina’s capital and largest city: taking in a Biennial hosted in a bunker, its tunnels and old cinemas, its best bars, and even its 1984 Winter Olympics site…

This summer, while thousands of visitors flock to Venice for the 57th Biennale, a trickle of tourists finds the way to a tiny town in central Bosnia, where they hope to see that country’s own Biennial of Contemporary Art. Back in 2011, I travelled to Bosnia Herzegovina (BiH for short) to witness the opening of the very first of these Biennials. And this year I made my way back there, to the fourth, which will be the final one. The town, Konjic, is about an hour’s drive from Sarajevo, the country’s capital. And the art can only be seen by appointment at the local tourist office. It’s worth going to the trouble of doing all this, though, because the Biennial takes place inside an enormous concrete bunker, built by the former communist regime inside a mountain, and kept strictly secret until its discovery after the breakup of Yugoslavia in the 1990s.

While Konjic is a sleepy, provincial town, Sarajevo is an international city. There’s plenty of choice about where to stay, from cheap B&Bs to modern, shiny hotels. My favourite area to be based is Baskarsija, or the Old Town, where a network of narrow streets full of little shops and cafes surrounds sedate Ottoman buildings like the Clock Tower (which keeps lunar time), the Bey’s Mosque, built in the early 16th century, and the old Silk Bazaar, the Brusa Bezistan. A short walk towards the river brings you to the Latin Bridge, where the Arch Duke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated along with his wife, one afternoon in 1914, sparking off World War One. Whichever way you look, Sarajevo presents itself as a focal point where civilizations and religions have met and overlapped: the Islamic world of the Ottoman Turks, the Imperial and Roman Catholic world of the Austro Hungarian Empire, and later on, the modernist and communist world of Tito’s Yugoslavia.

A couple of hundred yards along Obala Kulina bana, the street that runs beside the River Miljaka, in an old Austro Hungarian apartment block, is Sarajevo’s only independent contemporary art gallery, Duplex 100m2, founded by a Frenchman, Pierre Courtin, and named after the size of the apartment in square metres. Over the last few years, Courtin has discovered and curated shows by many of the region’s current leading artists, many of whom are now internationally-known, including Selja Kamaric, Adela Jusic, Selma Selman (pictured, top), and Dante Buu, whose current show was on when I visited. But Courtin is still struggling to pay the rent. There is no government support for contemporary art, so local museums including the National Gallery have all struggled to keep going. Artists, meanwhile, frequently have to live abroad to find enough work. On the afternoon of my recent visit, Pierre was chatting to Enes Zulsevic, a young artist from Mostar. He makes graphic animations and collages. One striking work brings together all the graffiti he could find in his home town in one image that Pierre was talking to him about installing across one wall at Duplex. Another work, an animation you can see on his website, plays with the image of a mirror and an old photo of his father, a Moslem soldier who died in the siege of Mostar.

Trapped in a loop from Enes Žuljević on Vimeo.

At the National Gallery, a big exhibition of photographs by Milomir Kovacevic Strasni documented the other siege – that of Sarajevo itself, taking place between 1992 and 1995, in which approximately 11,500 people died. Evidence of that siege, in terms of bullet holes and what are called “Sarajevo roses”, blast damage to the pavements caused by RPGs, subsequently filled with red wax to mark the deaths of civilians, are also hard to ignore. While many of Sarajevo’s oldest landmarks survived the siege unscathed, including the old Sephardic Synagogue that now houses the city’s Jewish Museum, others, like Vijecnica, the City Hall, did not: location of Bosnia’s National Library, it was targeted by Serb artillery in 1992 and over a million books burned, showering the city with tiny fragments of text. The building, an eccentric piece of Austro-Hungarian architecture in a kind of Moorish style, was slowly restored, and re-opened in 2014. I walked past it again during my recent visit; it was getting dark, the afternoon sunshine had given way to rain, but the building was decorated with red carpets and lit up for what looked like a Hollywood party, and hundreds of well-dressed young people were milling around having their photos taken. It was the city’s prom season, which proved so popular the police had closed the road off.

I had a different location in mind, however. That night I had gone in search of sevdah, the gypsy-inspired music that is beginning to be rediscovered and marketed as the “Balkan blues”, by musicians like Davir Imamovic. In the Old Town, a museum called the Sevdah Art House has its own courtyard cafe, where you can hear historic recordings of sevdahlinka from the early 20th century. Drinking coffee in Bosnia, by the way, is an important social ritual; it’s served strong, in tiny cups, and consumed with a lot of sugar, accompanied by conversation, and frequently a cigarette or two. I had been told that in this courtyard a local sevdah singer performs live every Saturday night. But on the Saturday I was there, a desultory waiter told me: “He’s gone to the Hotel Saraj.” So, after getting directions from the policemen at the road block, this was where I was heading, uphill, along a steep and winding road.

The Hotel Saraj, overlooking a dramatic view of the whole city, proved to be enormous. There were two ballrooms, with live music blasting from both. Folk tunes were being sung for Slovenian tourists in one, and, a couple of drinks later, I was joining in with the dancing, not knowing the steps, let alone the words of the songs. Upstairs, a wedding party was jumping up and down to live turbofolk — a far faster and more frenetic musical cocktail. But, that night, there was no Sevdah. Nonetheless, live music abounds in Sarajevo.

The trip to Konjic took up an entire day. Public transport in Bosnia mainly takes the form of buses connecting all the major towns. There are trains, but the railway system, starved of investment, hasn’t recovered from the conflicts of the 1990s. The Tourist Office sits beside the town’s famous bridge, which gracefully spans the River Neretva. Originally built by the Turks in the 17th century, it was blown up by German forces in 1945, and restored by the Turkish Government in 2009. Here, a van picks you up and takes you along the river to the Tito Bunker, which, from the outside, resembles a row of whitewashed houses, with shuttered windows. This is a deliberate disguise. Walking through the front door, you enter a series of increasingly wide corridors, taking you into a complex that would have accommodated 350 people including President Tito and his wife, and their top military leadership, in the event of a nuclear war. And the main threat to Yugoslavia, in the 1950s and 60s, came not from Western Europe or the USA, but from the Soviet Union, from which Tito had parted ways in the late 1940s.

In 2011, the Tito Bunker, or D-0 ARK, as it’s properly known, was still in the hands of the Bosnian Army, and at that time we had to go through a military checkpoint before we saw any contemporary art. Now, however, the Bunker is run by the municipal government, which seems to want to ration the amount of time anyone can stay in there. We had one hour, and were subject to a very stringent guided tour, led by a young woman who rushed us through countless rooms containing surveillance equipment, accommodation spaces (including Tito’s own bedroom), generators, fuel stores, and art. A lot of art, in fact, because all the art from the previous three biennials has remained in situ, the aim of the Biennial organisers having been to create a permanent collection of contemporary art within a unique Cold War museum.

It seems, however, that the local authorities do not care so much about the art. Many of the video installations were not working, the tour guide telling us that they would have been operational if we had arranged in advance for them to be switched on. Having not been informed about any of this earlier, however, no such arrangement could possibly have been made. But some outstanding examples of work were still unmissable. Annalisa Cannito’s Silence is Violence (2017), for instance, is a series of installations, including bullets suspended from the ceiling, and lightboxes displaying photographs of military warning signs to “keep quiet” — the kind of thinking that ensured the preservation of not just the Tito Bunker, but also the numerous munitions stores all over Bosnia that were originally intended to provide a defence against invasion, but ended up fuelling inter-ethnic slaughter.

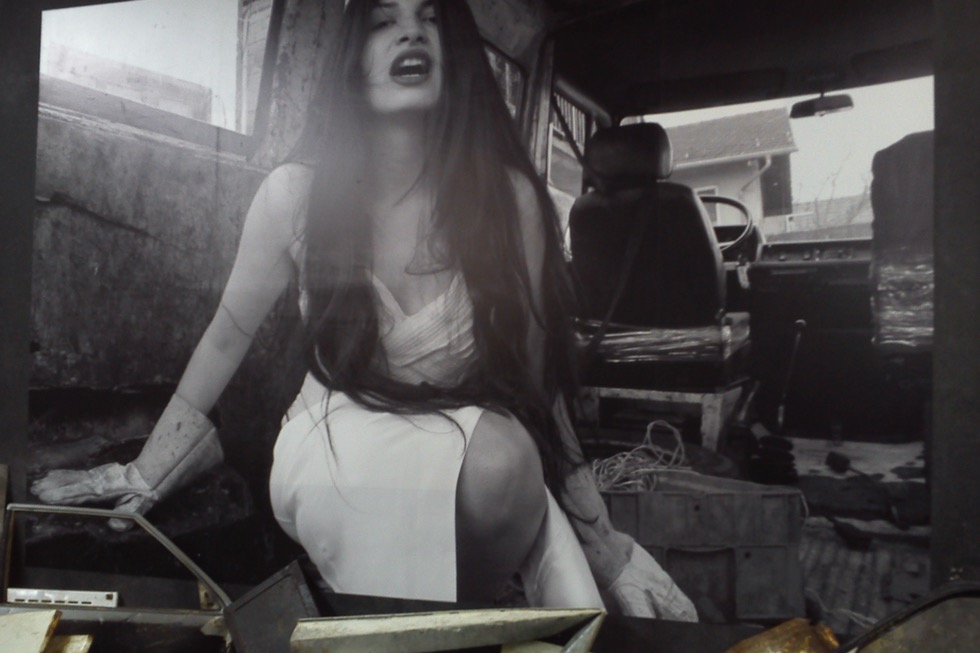

In what used to be the bunker’s map room, Damian Le Bas’s Roma Jugoslavija (2015), is the British-born artist’s colourful but troubling tribute to the history of Roma people in the region. And from another artist of Roma heritage, Iron Curtain/Mercedes 310 (2015), is Selma Selman’s powerful photo-installation picturing the artist hailing us from inside a van (top), with a pile of metal detritus, the sort of stuff Roma people reputedly buy and sell for a living, laid out in front of the image.

On the way back from Konjic, I took a detour at Sarajevo Airport in order to visit the Tunnel Museum (pictured, above), where you can walk through a section of the original tunnel that was excavated during the siege, in 1993, under the main runway, to provide a route connecting the city’s defenders with Bosnian army-controlled areas beyond the Serb lines. From here, a taxi was hired to return me to the city centre. Its driver turned out to have been a Bosnian soldier during the siege, and he insisted on taking me on a long journey up into the mountains overlooking the city, to show me the places where Serb forces had targeted the city. Their view over Sarajevo was clear and unimpeded. In amongst the forests that cover those mountains, the taxi driver also showed me the remnants of the concrete bobsleigh run that had been built for the 1984 Winter Olympics (pictured, below). It’s enormous, covered in graffiti, and resembles a kind of strange, stone snake.

Built for the same occasion in the city itself was a large shopping mall, the Skendarija Centre. Nowadays, it’s rather neglected, and has been damaged by heavy snowfalls in recent years. But it houses two important venues for anyone interested in contemporary art: a permanent collection of international work at Ars Aevi, which began being donated during the siege years, and the Collegium Artisticum gallery, which, when I visited, was exhibiting a group show called YEBIHA (standing for Young and Emerging BiH Artists). This included an intriguing-looking series of video performances by Mak Hubjer, Rest in Peace, War, and Clear Conscience (all 2017), and Dzenan Hadzihazanovic’s huge monochrome painting, Queue (2017). Ars Aevi is enthralling and time-consuming; work by Beuys, Abramovic and Pistoletto, among many others, is exhibited in front of the wooden crates the works will be transported in, once the collection gets its proper venue, designed by Renzo Piano, but yet to be built.

Walking distance from here, across the river and along a tree-lined avenue where many old embassy buildings are situated, is one of Sarajevo’s most popular places to get a drink and unwind: the Tito Café. Filled with Tito memorabilia and surrounded by a collection of broken-down military vehicles, the café is popular with students and bohemian-types. It’s a good place to start your evening, which, if it’s a Monday, should end up in one place only: Kino Bosna, an old, communist-era cinema that has been turned into a kind of artist-led cabaret. The drinks are cheap, the walls are covered in old posters, and onstage entertainment is provided by a band singing folk and pop songs accompanied by accordion, guitar and double bass. Later, in the traditional Bosnian manner, the band goes from table to table, performing especially for you and your friends. It helps if you know the words. But in time, after another visit, I think I may eventually start picking up the language.

Bob Dickinson

You can see the fourth Biennial of Contemporary Art in Tito’s Bunker, Konjic, near Sarajevo, Bosnia Herzegovina, until 21 October 2017