“They seem to fight to stop each other breathing”: Evangelia Kolyra’s 10,000 Litres — Reviewed

Who knew that breath had so much creative potential? Jacob Charles Wilson on a contemporary dance piece that will have you counting your intake, clawing at your chest, and synchronising with the people around you…

You are now aware that you are breathing.

From the moment you’re born, you don’t stop breathing. The sensation of it stopping is sudden, and wrenches you into a moment of full awareness. It happens rarely, sometimes at night in the midst of dreams; perhaps if you’re drowning. It’s a shock unlike any other. You need to be reminded of breathing because it’s so easy to forget about it, it comes to us so naturally. But it’s one of the few reflexes that we can learn to control, and pass from unconsciousness and into our consciousness. Once you gain control, you can change its tempo and rhythm, make speech, and excite the emotions. To the ancients, the breath of God was the source of art; today, we have ASMR videos.

And so to Rich Mix, London, for the premiere of 10,000 Litres; described by director Evangelia Kolyra as “a choreographic work which fuses dance, theatre and performance art”. It takes its name from the average volume of air that passes through your lungs each day. Kolyra recalls working in her studio when the moment of inspiration came to her: “I realised that the tiny movement of breath has so much potential in it which was fascinating to work with”. Collaborating with fellow performers Joss Carter, Victoria Hoyland, and Justyna Janiszewska, Kolyra explores the emotions and relations and communication that breathing fosters.

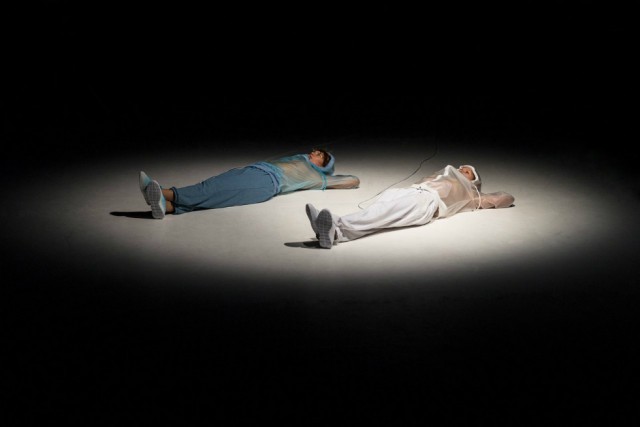

10,000 Litres takes place in a world unlike ours, in which performers shuffle and slide around the stage, worm-like, through a series of loosely defined sketches and scenes. The opening scene is like something from Samuel Beckett; Kolyra and Janiszewska lie in a spotlight discussing their place in the world, speaking to each other through inhaled words, with microphones amplifying the rustling of their costumes, every little gasp and squeak. The relation of one to another isn’t quite clear, but as their conversation wanders like a Markov chain, they share worries about the future; how to get there, losing themselves, and whether their friendship will last. It’s an introduction of what to expect; a dislocation of time and space, two bodies at once independent but connected.

10,000 litres_Teaser 1 from Evangelia Kolyra on Vimeo.

Of course, every performance is an interconnection of bodies across a stage, but in the history of dance, this has typically been between pairs, marking a clear relation between the two, more often than not along gender lines. By introducing a third performer, 10,000 Litres complicates and emphasises different power relations between the people on stage; creating a nuanced and complex set of relations that can’t always be broken down to binaries.

The pace quickens as the three dancers take up interlocking positions, balancing in acrobatic poses, blocking their partners’ mouths. Between their contorted forms, they seem to fight to stop each other breathing, only to change position when they can’t hold on any longer, before again taking a gulp of air and starting over. They get more desperate, more aggressive, as the scene goes on; scrabbling at mouths and noses and clawing hands off their own. You’re drawn into their desperate battle. This is an intentional move, Kolyra tells me, as the audience:

“Synchronise and identify with the performers, becoming very aware of their own breathing. In this way the audience becomes part of the work. As a performer, I feel that we are all transferred into a non-definable space which is a new reality for me, where I feel like being someone else, almost an alien creature.”

The direction of the work then turns towards the qualities of the voice, and its lack. Kolyra and Janiszewska take up two different roles: one a silent ventriloquist’s dummy, miming the words of the other, who, like a marionette, mirrors the first’s movements. The two sit on chairs, falling loosely from side to side, addressing the audience and no-one in particular, they move together and entwine their arms to fully take over the expressive gestures of each others’ bodies.

“I am a professional breath holder”, state the pair; “my record is 38 seconds”; before holding their breath and counting for roughly 38 seconds. Then, “nearly… let’s do it again”, and holding their breath again. It’s hard to tell whether it’s the voice or movement, the mind or the body, that comes first. Speech and its echo overlap; at points the body leads, other times the body lags behind as the voice speeds ahead. At other times the echo, voiced by Carter, arrives before anyone even spoke. As I try and look at all three, it’s difficult to follow the action. There’s no simple answer to who is directing who, as it’s perfectly staged, with flawless execution and timing.

If the whole work were like this it might feel suffocating, an intellectual weight on your chest. Thankfully, it’s broken up by light relief, which in turn breaks out into laughter through the audience. This underlying comedic current exists throughout the performance, being brought to the surface at opportune moments. There’s physical comedy as the dancers shuffle on the stage, wriggling and dancing like worms; there’s the ventriloquist act, as well as a few jokes (“The person who invented breathing forgot to tell you something really important — you should never lose your breath, you might never find it again”). The most direct humour comes from Carter’s clownish act, as he puts a harmonica in his mouth, breathing through it as he rocks himself backwards and forwards on a chair, trying to balance on two legs. His gasps are amplified through the harmonica into a ridiculous musical accompaniment. The three then join in a musical finale of harmonicas and shuffled dancing, before they return to the edge of the unlit stage. Having come literally to The End, there’s nothing else to do but finish.

I usually write about photography, but fundamentally, it’s the process and development of a work of art that interests me; how people define when the work is finished, what the idea of a finished work looks like, and how the audience completes the work. I want to know what kind of work Kolyra thinks this is: a play, a performance, a dance? Her vision is much more fluid. “The way it is performed changes every time as each one of us has a certain freedom as to how to do and say things”. So, it’s reflexive and responsive, but as it still retains something of a traditional structure — a prologue, action, comic relief, musical number, and a finale — it shows Kolyra’s work in theatre, and even leads me to describe the work as something like a variety act. But this format works to its favour; it’s not a complex plot, it’s perhaps even relaxing. I settle into my seat and, after a few minutes, notice that I’m breathing in time with the performers.

Hopefully, likewise, you’ve remembered that — while reading this — you ought to have been breathing.

Jacob Charles Wilson

Jacob saw Evangelia Kolyra’s 10,000 Litres at Rich Mix, Bethnal Green Road, London, on Friday 12 May 2017

@EvangeliaKolyra #10000litres