“The privilege of being an artist is the ability to answer back”: Art And Protest At Frieze Academy

How important is art as a form of protest? Does the best political art hold a pertinence across time, allowing it to retain a power for later struggles? Jacob Charles Wilson reflects on the recent — and acutely apt — Frieze masterclass…

The need to speak out and protest feels more urgent than ever before in living memory. Regressive values and dangerous politics are taking hold in the UK and abroad. But where should these protests be directed? Is it necessary to ask where art, as a set of cultural pursuits and as an industry, sits in this struggle, and how its institutions are positioning themselves?

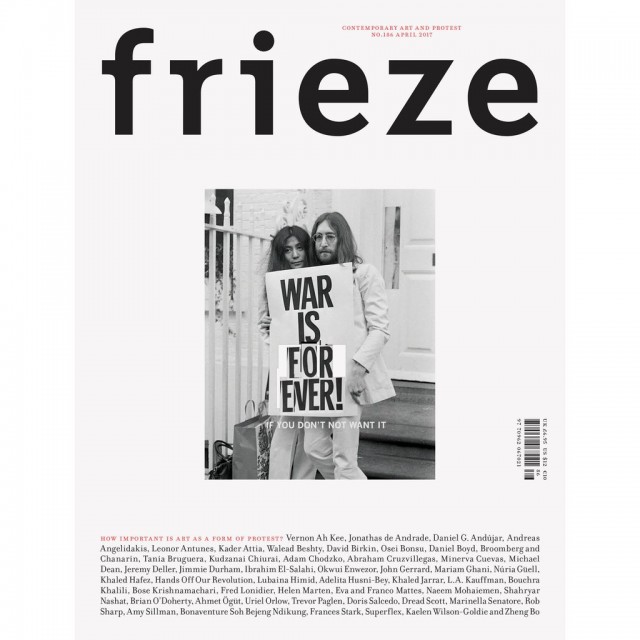

With this in mind, I joined a packed room a couple of weeks ago at the Rochelle School, London, to hear curator Osei Bonsu and artist-poet Heather Phillipson debate these pressing issues for Frieze Academy. The talk, entitled Art and Protest and chaired by Frieze magazine co-editor Jennifer Higgie, picked up on the theme of their April issue, fronted by Frances Stark’s detourned photo of John Lennon and Yoko Ono holding a sign proclaiming “WAR IS FOR EVER” (pictured, below). It’s one of 50 international artists responses, in images, text, and media, to two questions: How important is art as a form of protest?; and, How effective is it as a conduit of change?

Phillipson opened with a succinct summary of her position: “The privilege of being an artist is the ability to answer back”. In place of a formal introduction, the artist read extracts of poems from her exhibition more flinching (pictured, top), shown at the Whitechapel Gallery in early 2016 and emerging from her time spent there as a Writer-in-Residence. These poems arose as a result of her experience travelling through airport lounges, and watching coverage of the recent Bataclan terror attacks in Paris and the subsequent fallout.

What followed was a stream of associations that sped from allusions to the dislocated spaces of airport lounges, mediated by mobile technology, locked down by security barriers. The death of a police dog stood in place of her own pets, her own family members, and represented the power dynamic between dog and master. Higgie characterised the stream of associations as “a howl” against an entire mode of contemporary experience. more flinching offers a protest in the negative, against everything. Perhaps this is all art can do; but perhaps also, as Higgie noted, allusion gives political art a pertinence across time, allowing it to retain a power for later struggles in the way that a direct slogan can’t capture.

Discussion turned to Phillipson’s next major project. Her proposal THE END (pictured, below) – an overtly scatalogical sculpture of an enormous plastic coil of whipped cream, topped with a glace cherry, a housefly, and a security drone — was recently selected for the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, and is due to be exhibited in 2020. Phillipson admits she never thought she would actually win the commission with her plans to exhibit a pile of shit right in the middle of London.

But she has since refined her concept, relating this oversized joke to Trafalgar square as a site of official pride, protest, and colonial misery. She related her tactics to those of the Dada movement, born exactly a century ago during the carnage of the First World War, who used created an aesthetic of rejection and irreverence to destroy the European high class culture that had in turn started the war. The speakers introduced the politics of humour into the discussion, noting that it’s an often underrated factor in protests and the longevity of artworks; those by Dada artists such as Hannah Höch and Kurt Schwitters today still retain something of their original impact. But the political composition of the mainstream has moved so rapidly that it provokes speculation about how THE END will be perceived in 2020, as a timely intervention or a dated folly.

It’s precisely the pace of change of the contemporary world that concerns Bonsu, who introduced himself as a writer and curator working with the hyper-connection of people, including the Internet and modes of image-making outside of the art world. Where Phillipson described how protest may appear in art, Bonsu directed his attention towards the space of protests, where it occurs, and its intended result. There was a general agreement amongst the speakers that all acts are political, that no single experience or tactic should be considered more valid or significant than any other. Bonsu highlighted that after a decade or two of “the personal” being considered as passé in political art, that there has been a return to identity centred politics — a move he’s not opposed to. Though Bonsu warned of the degree of expectation that is placed on artists of marginalised identities; that they ought to produce political work only concerning the qualities that made them different in the eyes of mainstream groups.

Bonsu introduced a criticism of the digital space of protest and art-making, characterising this as “clicktivism”; the signing of petitions, the liking of statuses, the sense of an engagement with an issue. He positioned himself against the idea that everything is available to everyone on the Internet. Phillipson and Higgie agreed that they saw a dead-end in online-only tactics, that action was rarely translated into change. Bonsu also noted that the issues that get most attention are not necessarily the most pressing or relevant to many people. I saw something of a contradiction in this with the assertion that all acts are political and there shouldn’t be a hierarchy of tactics.

This wasn’t picked up by the speakers, but was highlighted by audience members who genuinely interrogated them, engaging with their points and providing counter positions; a relationship facilitated by the intimate space and the clear arguments made during the talk. One audience member related the social impact of imagery and artwork made in the South African #FeesMustFall protests (pictured, below); with social media being used to both promote the aims of the protestors, and to affirm and organise their presence through shared images and memes.

There’s a common way of talking about the autonomy of art — Bonsu commented that art is a form that has historically taken a step back from the urge to produce an immediate and direct reaction — but this is a very specific understanding of the word Art; one that’s only recently been developed and one that I’d criticise. What about the Dadaists, the Soviet Constructivists, or even Jacques Louis David’s masterpiece of the French Revolution, The Death of Marat? Bonsu’s statement sidelines the fact that the vast majority of artists don’t work exclusively within the art world and don’t exhibit in fairs. They work outside of it, in front-of-house roles or in retail, they are unemployed, or their work isn’t considered Art with a capital A. How many artists work for creative firms in advertising? This is besides the artists excluded by virtue of language, location, or political status.

In fact, people who call themselves artists rarely have the opportunity to separate themselves from the issues of work and life; their practice is intimately entwined with and responds to these issues. To frame artists as uniquely philosophical, considered, and insightful demeans what artists can, and do, learn from outside of the art world.

That art is distinct while intimately bound up in life leads to the problem of reception. Bonsu noted that often despite their best intentions artists exist at the intersection of art and money. How can artists, critics, and audiences remain moral while also selling and appreciating art? It was recently revealed that many of Trump’s top donors are art collectors, and some of the most prolific collectors in the UK are linked to arms dealing and other ethically questionable investments. Ultimately, these questions aren’t limited to artists, but extend from to the entirety of life under capitalism; if there’s no ethical consumption what can we do? Protests in the negative — purely against something — can be co-opted; the failure of The Occupy Movement shows that no achievements can be made from a deliberate refusal to make demands.

Higgie said she saw art as providing a propositional mode of protest, as demonstrating potential route out of predicaments. Bonsu then offered the possibility that Frieze magazine itself become propositional; not just responding to what’s new and current, but seizing the moment to direct attention to what’s important and relevant. Higgie seemed to suggest that there had been an editorial discussion on the matter, but rejected the idea of the magazine taking a more distinct political angle.

The task of criticism is not to simply review the subject of debate, but to question the framing of the debate itself. This requires the reviewer to take a step outside the artwork and propose an alternative; an action that in turn expands the horizons of thought, and parallels the postpositional form of protests. This isn’t as radical a change as it seems; the political choices of the reviewers and the editors are already there, in the omission of certain artists, in the pairing of one work to another, and between the lines of text. To bring political aims to the surface of the page may appear controversial from the viewpoint of an industry-leading magazine that doesn’t want to alienate a potential audience, but at the same time, it’s the foundation of robust debate that artworld — and the world at large — desperately needs.

Jacob Charles Wilson

Jacob saw Art and Protest with Jennifer Higgie at Frieze Academy, Rochelle School, London, on 27 April 2017

Images, from top: more flinching, 2016; installation shot, courtesy Whitechapel Gallery and Heather Phillipson. THE END, Heather Phillipson’s selected proposal for the Fourth Plinth, Trafalgar Square, on view at the National Gallery, London, 19th January –27 March 2017 / on display at Trafalgar Square, 2020 – 2021; image credit James O Jenkins. #FeesMustFall protests, courtesy Afrika Reporter