Urban Vibrations: Sound, Selfhood And The City In The Work Of Magda Stawarska-Beavan

Start listening again: Dr James G. Mansell investigates the “deeply personal” sonic artworks of Magda Stawarska-Beavan…

Listen. What can you hear? All quiet? Or is there a noise?

Most of us rarely pause to consider the sounds around us. Barricaded by headphones, cocooned in car stereos, or huddled behind double-glazing, everyday sounds have become little more than auditory clutter to be shut out or ignored. Sociologist Georg Simmel observed in the early 20th century that urbanites had to put up their perceptual shutters or risk the prospect of mental overload. Simmel’s reflections on the newly booming cities of his time remind us that our relationship with sound evolves along with our changing ways of living with each other. In my new book The Age of Noise in Britain: Hearing Modernity (2017), I trace the historical processes that went into producing our distant and hostile attitude to everyday sounds. Noise abatement campaigns from the 1920s onwards convinced us to retreat from urban sound, to treasure auditory isolation and to defend our right to quiet. The move from slum to suburb was a shift from hubbub to hush and we became ever-more isolated in our individual sound worlds. But what do we miss when we choose to stop hearing? Examining this question historically is one way to appreciate that how we hear is part of who we are, but it isn’t the only way.

Artist Magda Stawarska-Beavan takes a different approach. Evolving a critical ear by listening directly to the sounds around her, Stawarska-Beavan’s sound works invite us to step out of our auditory isolation and to start listening again. In his pioneering book Rhythmanalysis (2013), Henri Lefebvre suggested that in order to understand the social patterns that structure our everyday lives, we might be better to listen up than take a closer look. Rather than thinking-it-through, he suggested that rhythmanalysts should use their bodies to feel the shape of social life. Arguing that power and control operate as much through time as through space, Lefebvre invited us to hear our communal rhythms once more. Stawarska-Beavan is a kind of rhythmanalyst. She is a wanderer, a modern day flâneuse, drifting through the city while paying attention to its sonic undercurrents. She invites us to join her in these wanderings: the binaural microphones and digital cameras that she attaches to her body capture a kaleidoscope of sensations as she goes. Moving through urban spaces, she documents the everyday sounds that envelop us. While most of us rarely stop to consider these fleeting sensations, Stawarska-Beavan asks us to confront them, editing them into rich collages of urban experience in her art works. She enters deep into the vibrations and reverberations of place that we rarely notice.

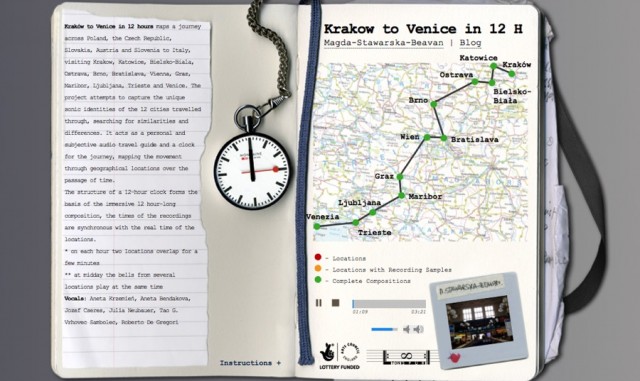

She is an outsider, deliberately targeting unfamiliar places to hear them afresh. In preparation for Kraków to Venice in 12 Hours (pictured, below), Stawarska-Beavan travelled through Kraków, Katowice, Bielsko-Biala, Ostrava, Brno, Bratislava, Vienna, Graz, Maribor, Ljubljana, Trieste and Venice, recording as she went. The resulting 12 hour, 8-channel audio piece offers us an auditory snapshot of each city, capturing the “unique sonic identities” of each place, through the sounds of its bells, public transport systems and other local sounds, as well as the harder-to-identify ambiences, atmospheres, and echoes of voices, footsteps and daily goings on. In Kraków to Venice, these sounds are overlaid with whispering voices which count in Polish, Czech, Slovak, German, Slovenian and Italian, as well as Romany, drawing our attention to the passing of time and to the linguistic barriers which exist around and across nations.

The effect is to draw us in and to alienate us from place, to offer us a glimpse of what it is to belong to a soundscape as well as what it is to be an auditory outsider. A resident of Kraków or Venice might warmly recognise the sounds of their own cities, but they must also confront the alienating impact of the juxtaposition with other places’ sounds, as well as the unsettling insistence of the whispered beat. A defamiliarisation of sonic place is achieved which causes us to reflect on our own relationship to daily sound and on what it means to traverse sonic boundaries. These boundaries are an explicit theme of the work; sonic borders between nations, communities, bodies and spaces are elucidated as we listen with Stawarska-Beavan. As we move from one place to the next she draws our attention to the different layers of place: not only do we move around and through physical spaces and divisions, we also encounter the sonic boundaries of language, auditory communication and atmosphere. The work comes with accompanying maps, a website and a blog, but on its own the sound is an exercise in deep and concentrated listening that is both entrancing and alienating. Sounds can make us feel at home and give us a sense of belonging. They can also make us feel unsure, out of place, and far from home.

Stawarska-Beavan is, above all, interested in the sonic border-crossings that give us our sense of ourselves. Remembering the experience that first inspired her to work with sound, she recalls staying in a hotel room in Barcelona which looked out on to a major city square. The square reverberated with city sounds day and night and she felt these sounds “vibrating within me, piercing my sleep.”

“I was in the city,” she explains, “but I also felt like part of it”.

Sound does not respect the traditional spatial logic of insides and outsides. It moves through places, but it also moves in and out of us. We feel it and remember it. To explore sound is to explore who we are and who we might become. Stawarska-Beavan points to a favourite quote from Frances Stoner Saunders: “…the self is an act of cartography and every life a study of borders… We construct borders, literally and figuratively, to fortify our sense of who we are; and we cross them in search of who we might become.”

Stawarska-Beavan does exactly this in East {hyphen} West: Sound Impressions of Istanbul, a double limited-edition vinyl recording with artist’s book. The six sound collages which constitute the work capture the sounds of Istanbul at a particular moment in time from the uniquely personal point of view of the binaural microphones which she attaches to her ears. Again, Stawarska-Beavan focuses on sonic borders, this time on the meeting of East and West in Turkey. Through the technique of juxtaposition Stawarska-Beavan draws our attention to the combination of voices and musics which unmistakably position us between continents. The Bosphorus river also features prominently as a sonic border: Stawarska-Beavan captured its sounds both above and below water, using hydrophones, drawing us away from the familiarity of human-made sounds into the ambience of nature. She explains that while she was “conscious of exploring geographical, cultural and continental borders, I became aware that the peripheral border of my outer self had become the collection point for the data”.

As with Kraków to Venice, then, East {Hyphen} West is very much an exercise in listening with Stawarska-Beavan. This is not a soundscape captured for the historical record; it is an exploration of what it is to hear and to experience sound, narrated necessarily from the point of view of the artist-hearer, remembering, feeling, and moving through sound in an unfamiliar place.

As an historian, limited necessarily to what is available to me in the historical record, I envy the direct relationship which Stawarska-Beavan develops with everyday sound in her work. But I can learn from her too. She reminds me that our everyday relationship with sound is deeply personal, intermingling with other sensations, with feelings and in turn with memory. As a historian I try to listen with my historical subjects rather than listen to their sound worlds. By this I mean that when we hear, we do so as particular kinds of subjects living in particular times and places. How we hear is shaped socially as well as biologically. I pay close attention to people’s recollections of sound in order to try to make sense of historical ways of hearing. Stawarska-Beavan does this instinctively as she traverses the sonic borders that hold us in place. She shows us that to hear is to belong. She shows us, too, that listening carefully to others opens new possibilities for who we might become.

James G. Mansell

This text forms part of a series of essays, commissioned jointly by In Certain Places and The Double Negative, which has been developed through Practising Place – an ongoing programme of conversations, designed to examine the relationship between art practice and place. Each event is hosted at a different across the country and explores a specific aspect of place by bringing artists together with other researchers who share a common area of interest.

This essay was written by Dr James Mansell in response to his conversations with artist Magda Stawarska-Beavan, which began at a Practising Place event in Nottingham in 2015 and can be viewed online here.

Practising Place is part of In Certain Places – a programme of artistic interventions and events based in the School of Art, Design and Fashion at the University of Central Lancashire. For more information visit www.incertainplaces.org.

Magda Stawarska-Beavan’s practice is primarily concerned with the evocative and immersive qualities of sound. She is interested in how soundscape orients us and subconsciously embeds itself in our memories of place, enabling us to construct personal recollections and, moreover, it offers the possibility of conveying narrative to listeners who have never experienced a location. She works predominantly with sound, moving image and print, often connecting traditional printmaking processes with new technologies such as digital audio.

Dr. James Mansell is Assistant Professor of Cultural Studies in the Department of Culture, Film and Media at the University of Nottingham, where he also co-directs the Nottingham Sensory Studies Network, a research cluster supporting sensory work across the disciplines. His research has focused on the cultural history of sound and hearing, sound media, and on histories of sonic modernity and modernism. His forthcoming book The Age of Noise in Britain: Hearing Modernity will be published in the autumn by the University of Illinois Press.