“Playing With Time”: Artist Luke Ching Makes Giant Pinhole Camera For LOOK/17

Photography made from a pinhole camera the size of a hotel room will be the star attraction at LOOK/17 festival. Pete Goodbody meets the artist, Luke Ching, to hear more about his peculiar and intense set-up — which includes living in the same room, in the dark, until the exposure time is complete…

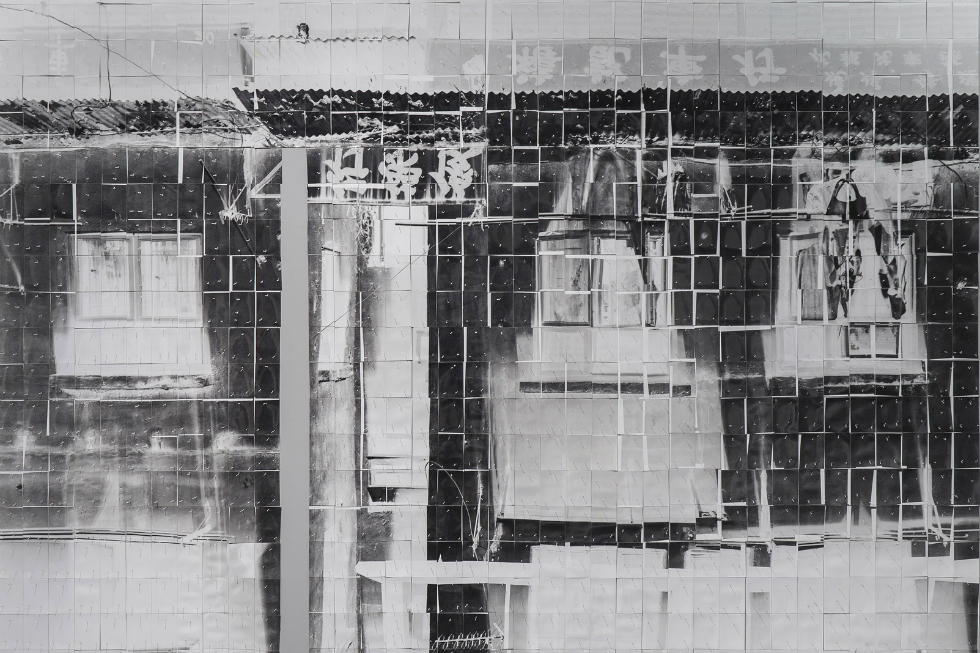

You might be surprised to learn that digital photography will not be occupying the prime spot at LOOK, Liverpool’s International Photography Festival 2017. Instead, expect a more traditional, unpredictable format: pinhole photography. Created by Hong Kong-based artist Luke Ching during a week-long residency at the Titanic Hotel on Liverpool’s North Docks, during a chilly January 2017, Ching built a camera obscura the size of an entire room — although he prefers the term “pinhole room”. He’s an ideal choice for the festival’s theme, Cities of Exchange, as he uses an unexpected medium to consider how the language of photography is used to experience and shape the city.

This year’s LOOK festival will welcome Chinese photographers to the UK – via a close working relationship with Open Eye Gallery and former CFCCA curator Ying Kwok — and will explore images taken in Hong Kong and Liverpool; cities with a long history of commercial and creative interchange.

When I meet with Ching, he describes how his pinhole camera images are projected onto a vast collage of A3-sized photo sensitive papers, pinned all over one wall in his hotel room, and thus exposed to the image created by the tiny pinhole lens. The exposures are long: in the case of one image, 24 hours long. Unbelievably, throughout the exposure, Ching lives in the room, never turning on the lights. It’s difficult to imagine such a commitment, which seems comparable with meditation.

This temporary and intense residence is important to Ching. Many will know the Titanic Hotel building and its neighbouring Tobacco Warehouse as significant, historic structures; built in the 19th century and a meaningful part of Liverpool’s past as a port city, as well as its present iteration as one of tourism and culture. By contrast, Ching’s stay is transient; he acts as a tourist, renting a hotel room for a short period of time. The huge camera that he constructs in this room is a temporary object; installed for about three days, then dismantled; the room returning easily to its intended use. It’s as though he was never there.

We discuss this temporary transformation of an unassuming room into a giant camera as a relatively short period of time in comparison with the life of the building. There is another contrast of time; compared with a “normal” camera’s exposure, usually measured in fractions of a second, the long exposures of the pinhole camera give Ching the chance to have a more considered relationship with the building. He calls this “playing with time”.

Ching’s other artworks also reflect a certain playfulness. Screensaver (2013-14) is a series of CRT monitors, each displaying a corporate logo. Over a period of about six months, Ching made sure that the image was burned onto the monitor’s screen, creating a permanent image on the display. This type of screen-burn doesn’t affect modern LCD or plasma monitors, but it was a problem in the early days of personal computing, and it was the reason for the creation of screensavers: a constantly shifting image displayed so as to prevent the creation of a permanent, ghostly image. Ching’s piece endeavoured to do the opposite.

He likes waiting, Ching explains. Another piece, entitled The Happy Princess, had Ching filming a pair of statues in Manchester in 2012. He waited to start filming until a pigeon landed on the statue’s head, and then filmed until the pigeon left. It took him 12 days to get about six minutes worth of footage.

The pinhole camera images are part of a project Ching has been working on for more than 16 years and, he says, is likely to carry on for many more. Some of these images were shown at his exhibition For Now We See Through A Window, Dimly, at Gallery EXIT in Hong Kong at the end of 2016. Ching tends to focus on architecture as a metaphor for our times. Most of his photography is of structurally or historically noteworthy buildings. But some, such as a photograph taken at the Hong Kong squatter town of Pok Fu Lam, show the temporary life of structures. This reflects something of modern day Hong Kong, where Ching thinks real estate is treated more and more like a consumer good – a commodity to be bought and sold for money rather than a place in which to live on any long-term basis. Again, we see Ching returning to a theme of time.

He says he is seen as a conceptual artist at home in Hong Kong, and although he does work with other media, perhaps the pinhole shots are the clearest way to see and understand Ching’s fascination with the concept of time and his demonstration of the contrasts. He is very much an artist first and a photographer second: “I just know how to do pinhole”, he insists. As a vehicle for expressing his ideas, this tool seems to be a perfect fit.

The other thought-provoking effect of the long exposures Ching employs is to remove any people or movement from the image. This, then, focuses the work on the architecture, which Ching says should be intended to last, but is so often not the case these days. That is why he found working in the Titanic Hotel so stimulating, as its long history as a commercial warehouse created a contrast with his temporary residence. Yet, he hopes the images created there will speak to Liverpool’s more permanent residents, not just the tourists, as he was for a time.

Pete Goodbody

See Luke Ching at Open Eye Gallery as part of LOOK/2017 from 7 April to 14 May 2017 — FREE

Image, top: Luke Ching’s pinhole camera photography, courtesy the artist. Middle image: Ching in Liverpool during his residency, and bottom, a close up of his work — both image credits courtesy Pete Goodbody