Utopia Deferred? Paul Collinson & Mandy Payne On Depicting The Perfect World

An impossible dream, or an ideal worth striving for? To mark Corke Gallery’s Utopia Deferred exhibition, C. James Fagan speaks to two of the exhibiting painters about the concept of paradise…

Painter Paul Collinson remembers the place of his childhood, a 1950s council estate on the outskirts of Hull, as a place “geographically and psychologically not a suburb of anywhere.” To add to this sense of non-place, he describes “the roads had been laid out, but the estates were never built.” A utopia, you could say, that was never realised.

I’m speaking to Collinson about his paintings, and about the term ‘utopia’, ahead of the opening of his new group exhibition Utopia Deferred, with fellow painters Mandy Payne and Conor Rogers. Currently on display at Corke Gallery, Liverpool, the touring show from the three artists – all of whom have been selected for various editions of the John Moores Painting Prize – takes its title from a 1972 Baudrillard essay of the same name; exploring different aspects of the contemporary landscape, and challenging our ideas of the perfect world. It is a recognisable realm of housing estates, spaces left to seed, and the remains of a delayed, possibility forgotten utopia.

It’s a great moment to revisit the term and its original meaning; and, for that matter, its sibling, ‘dystopia’. I grew up at the end of one of these attempted utopias, in a new town called Runcorn in the North-West of England. Like other new towns, Runcorn’s 1970s estates were created to solve the ‘dystopic’ living conditions found in many Post-War cities:

“Its proportions, its sequence of squares, and its abstracted-colonnade main façades were based on the Georgian precedents of the cities of Bath and Edinburgh. Runcorn offered a high-density, low-rise (five-story) solution to the national housing problem at a time when Victorian ‘slums’ in nearby Liverpool were being demolished in swaths.” (What Went Wrong at Runcorn?, Architect magazine (2010))

The origins of the word utopia, however, stretches much further back than ’70s Britain. The satire Utopia was written 500 years ago by lawyer, writer and statesman Sir Thomas More; a thought-experiment into the need of the human race, to regiment the behaviour and landscape alike. More’s utopia was an imaginary state; an examination of the attempt of humanity to save itself, from itself.

More’s version wasn’t the first attempt to put forward an idea of the perfect society — see Plato’s The Republic (written around 380 BC), and Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1627). History is littered with attempts to bring about a utopia, inspired by religious, political or social ideas. Consider the Amish communities of Pennsylvania; the Communist revolutions in Russia (1917) and China (1949); Le Corbusier’s Modernist architecture for better living; the American 1960s Hippie communes of Drop City or Arcosanti.

My definitions of utopia or dystopia weren’t directly formed from environment, however; rather from science fiction. Dystopia as portrayed in Mad Max, Clockwork Orange, 1984, Judge Dredd, Blade Runner and High-Rise. I soon found out that utopian sci-fi — like Star Trek and Iain M. Banks’ Culture series — is far from perfect.

A problem with trying to create a utopia is that no one can agree on what a perfect society is, or on what form that brave new world should take. With so many differing ideas floating around, it leads me to wonder why people would actually want a utopia at all? As Collinson tells me, there is something very untoward at the heart of paradise. “Do we want utopia? Utopia is always dystopian… Utopias after Plato’s Republic depend on humanity’s acceptance of regimentation and enforced hierarchy.”

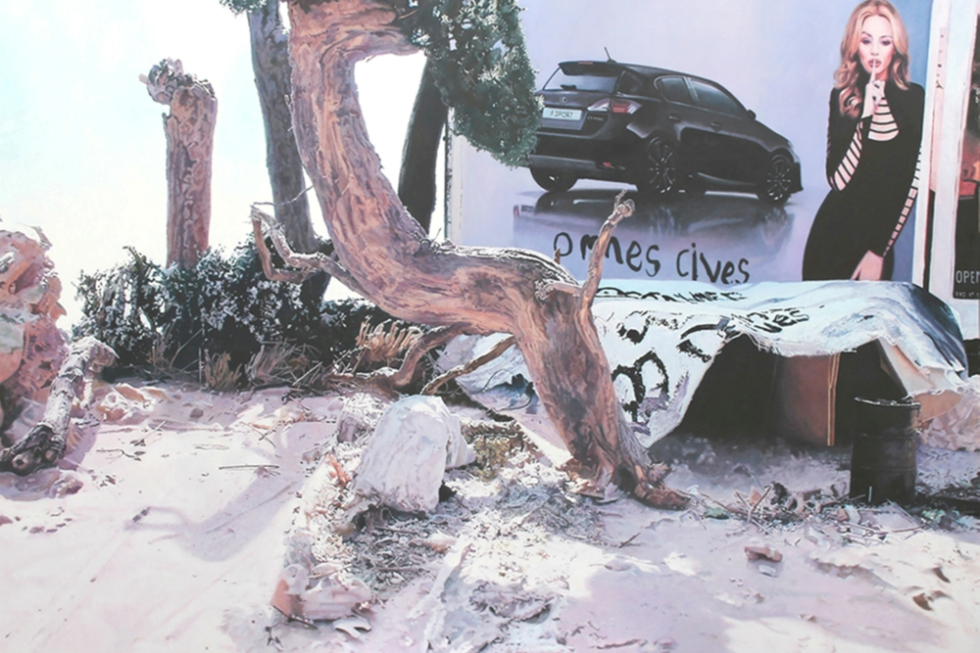

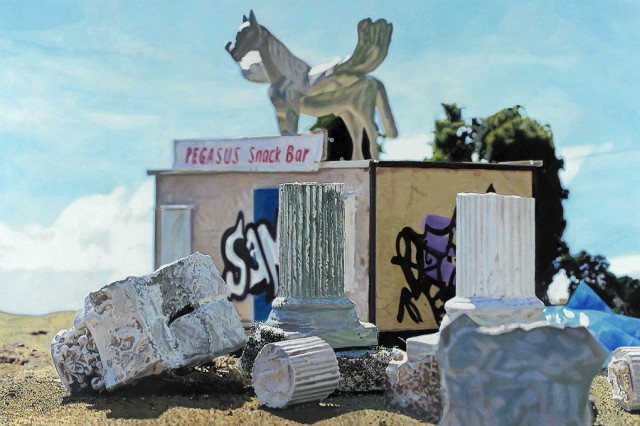

This imagined space in Collinson’s work – utopian or dystopian, you decide — is further enhanced through his method of producing miniature models, which are meticulously photographed and then transformed into paintings. Becoming, as he describes, “extrapolations of my own imaginings”. You can see this strange perspective in his painting Temple of Ancient Virtue (last image, below), which was chosen for the 2012 John Moores Painting Prize.

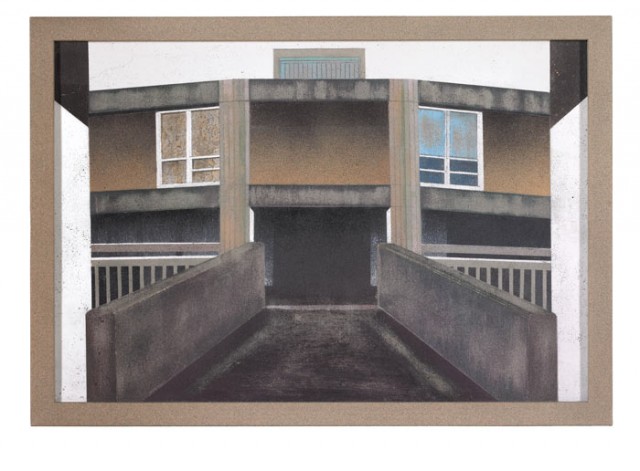

Utopia Deferred co-exhibitor Payne also touches on this idea of inhabiting a mental or imagined space; only in Payne’s case, it is memory that is being explored. Payne’s aerosol-on-concrete portrait of a walkway from the Grade II-listed Park Hill estate in Sheffield, entitled Brutal (above (2013)), was one of the prizewinners of the 2014 John Moores Painting Prize, and she has again been selected for this year’s exhibition with No Ball Games Here. Payne explains that her intent isn’t to disrupt an ingrained view. Rather to “paint what is there”, and what is overlooked, in order to see the beauty in the everyday. Having visited Sheffield and Park Hill, I can confirm that it has a singular beauty; admittedly one that may not be universal. Payne depicts the “temporality of the urban landscape”, as she puts it, and with it a loss of community. In doing so, she raises an interesting point regarding utopia. How fixed can it be?

By focusing on the Park Hill estate, Payne draws on its history and the legacy of related projects across modern Britain. After the Victorian slums, the residents of Park Hill could have been said to see it as a utopia; yet that original promise was comprised by changes both social and economic, plus a lack of investment and maintenance which led to a significant decline. I see this in my own home town; where the Southgate estate was used as a dumping ground for ‘problem’ people.

While not overtly political, Payne sees her paintings as a “possible metaphor for the lack of affordable homes and social housing [provided] by previous governments.” This is further compounded by the fact that comparable areas are right now being redeveloped for new residents external to existing communities, like Liverpool’s Welsh Streets; in other words, gentrified.

Perhaps we could consider Margaret Thatcher’s Right to Buy scheme (1980) as an attempt to establish a utopia. On this subject, Collinson mentions how this idea of owning your own home came from “defensible spaces”, as put forward by architect Oscar Newman. Basically, if you own something, you’re more likely to defend and maintain it.

Collinson notes that Thatcher’s version of defensible spaces merely depleted the stock of affordable housing.

Coming back to sci-fi, and to utopia depicted in culture more generally, I also ask if it’s possible to create art within a utopia, and whether utopias are boring to depict. Both Payne and Collinson see utopia as a place art cannot be generated. Collinson refers to Plato’s vision of the artist (in The Republic) reduced to producing uniforms and relaxing music for the workers. Payne states that it is the imperfections and flaws of the unrestored places, like Park Hill, that she is drawn to as an artist.

And as we know in Heaven, there are no imperfections.

Expanding on the problematic role of art in utopia, Collision sees the artist as an outsider; the rebel with no place in a perfect society. The artist’s position is to challenge, or to provoke, the status quo.

The idea of utopia, or the perfect society, is seemingly destined to be contradictory. Utopia is a place where peace and happiness require the surrendering of personal freedom and even creativity. Utopia is a place which has attempted to manifest itself physically, though the action of individuals, whilst being thoroughly rejected by society at large. Utopia is something over the horizon, where it’s brighter but it’s not now, not here, and not for us. Yet we continue to demand it and strive for it, as Payne perfectly summarises: “Thomas More’s description of a society free of suffering and poverty must be an ideal worth striving for.”

C. James Fagan

See Utopia Deferred at Corke Gallery, Liverpool, until 9 September 2016 — FREE. Gallery opening hours Wednesday to Friday between 1-5pm

Images, from top: Utopia Deferred exhibition: Paul Collinson, Cold Pastoral (2014); Mandy Payne, Looking Forward Looking Back; Mandy Payne, Brutal (2013); Paul Collinson, Temple of Ancient Virtue (2010)

See Conor Rogers’ 88 Calories, as featured in the 2014 John Moores Painting Prize

Follow the Utopia Deferred artists on Twitter: @englandsfavour1, @mandypayne24, @conorrogers_art

Listen: Playlist: Utopia Deferred