“The real heroes have not been celebrated” — The Big Interview: Jon Daniel, Afro Supa Hero

Post edit: We are incredibly sad to report the recent passing of Jon Daniel. Last year our writer James West interviewed the designer about his far-reaching portfolio and career of 25 years (below). RIP Jon, 1966–2017.

From Malcolm X and Shaft action figures to comic books about slavery and Luke Cage: designer Jon Daniel talks to James West about the “universally cool” explosion of Black pop culture from his childhood in the 1970s, and how his new exhibition in Liverpool is trying to address the issue of deleted histories…

Born in London in 1966, Jon Daniel trained as a graphic designer before working as an art director for many of the UK’s leading advertising agencies. He later co-founded and directed two creative companies: the creative partnership Headland, and the boutique branding company ebb&flow®. For the last five years, Daniel has been committed to developing new projects centred around collecting, and of diasporic history; interests which fed directly into the development of his latest exhibition Afro Supa Hero, which opens at the International Slavery Museum today.

As a child growing up in a predominantly white area of South West London, Daniel found positive role models through his family’s Caribbean heritage and through African American popular culture. As an adult, he began to collect comics and action figures which featured positive black role models, that provided a window into his own childhood and search for identity. Afro Supa Hero is a heartfelt and biographical journey through pop cultural heroes and heroines of the Black diaspora, and a loving nod to the often neglected history of black comic books and superheroes.

I caught up with Daniel at the 198 Contemporary Arts and Learning centre in Brixton to talk about the exhibition, its connections to his own family history, and his advocacy for diversity within the creative and cultural industries.

The Double Negative: What was your first experience with comics or superheroes as a child?

Jon Daniel: I’d say the most vivid one for me was Look and Learn [British educational magazine]; there was a comic strip in there called The Trigan Empire which I used to love reading. As a child, I wasn’t that much of a comic person, but there were two comics in my early teens which I loved: Jonah Hex and Sergeant Rock.

Were you much of a comic collector during your teenage years?

I had some comics, but I wasn’t too attached. Like most people my first real collection was music; when I was 14/15 I got into P-Funk [funk music associated with George Clinton and the Parliament-Funkadelic collective], and that superseded everything. I got into buying all of the different vinyl: Parliament, Funkadelic, Bootsy’s Rubber Band, you name it.

There are so many iconic, black comic book heroes who are introduced during the 1960s and ’70s – Black Panther, Misty Knight, Black Lightning, Luke Cage, etc. Is your interest in them retrospective?

Definitely a retrospective thing. I wasn’t really aware of heroes like Black Lightning or Luke Cage as a child. But I was always acutely aware of my colour and acutely aware of wanting to find other role models.

So when did that exposure to comics first happen?

When I went to the States on a family holiday, suddenly everything made sense in terms of the culture and how it’s celebrated. You turn on the TV, and, oh my god, a black sitcom! Wow! I was like: “You guys head back to England, I’m staying here.”

Where do you have family in the US?

All over really, but on my Dad’s side, it was mainly New York, New Jersey and Cleveland. On my Mum’s side, coming from Grenada, so Canada was a big place. My aunt went to Toronto, my brother lives in Calgary. We had some big family reunions when I was younger, huge events where we would take over a whole hotel, 250 of us. First one was around 1979 in Barbados.

When did you start collecting action figures?

1994. The first figure I collected was made by Olmec toys, and it’s a Malcolm X action figure. At that time, people didn’t know that much about black action figures – certainly I didn’t – but the concept that there was a Malcolm X action figure was so powerful to me, so I bought it. And it set me on this journey to see what other black action figures are out there – [Olmec] had done a Martin Luther King one, they’d done other stuff. It was set up by a woman called Yla Eason, because she was looking for toys that would be culturally relevant.

Prior to starting that collection, I’d actually had a collection of stamps, which was connected to a campaign to have a set for black British heroes and heroines – you know, like the Public Enemy song Fight the Power: “I’m ready and hyped plus I’m amped. Most of my heroes don’t appear on no stamps”, I designed a set of stamps and petitioned Royal Mail to do them. They never did. But I campaigned for a long time and had a lot of good people on board. It turned into something I was excited about.

Do you have memorabilia relating to some of the earlier, more problematic black comic characters, such as Ebony White?

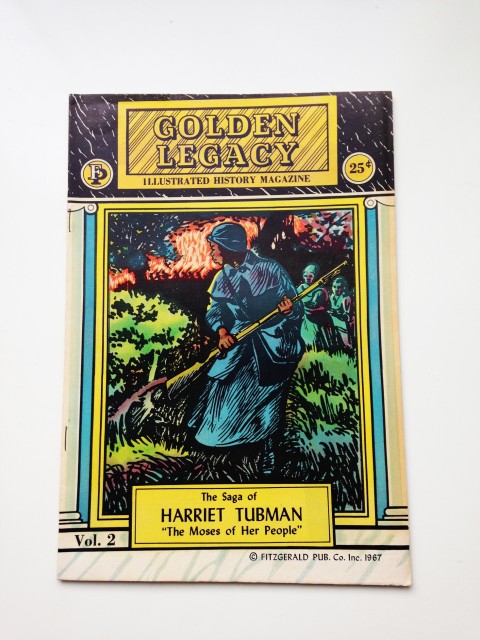

The oldest comic I’ve got is Lobo, which is 1965 [the first series to be driven by a black lead character and to include issues of slavery and the Civil War], and Golden Legacy, which is around the same time, 1966 [illustrated history series]. They all really stem from around the mid-1960s and 1970s, largely because it’s the era that most represented my childhood, but also in terms of that being a really dynamic time for black popular culture generally.

Does the Afro Supa Hero exhibition have a soundtrack?

No, although if it did it would be P-funk, no doubt about it.

What is your favourite model?

I’d have to say Super Agent Slade, made by Shindana. Probably the closest the thing you can get to a model of Richard Roundtree as Shaft [1971].

What’s the most expensive piece of memorabilia in the collection?

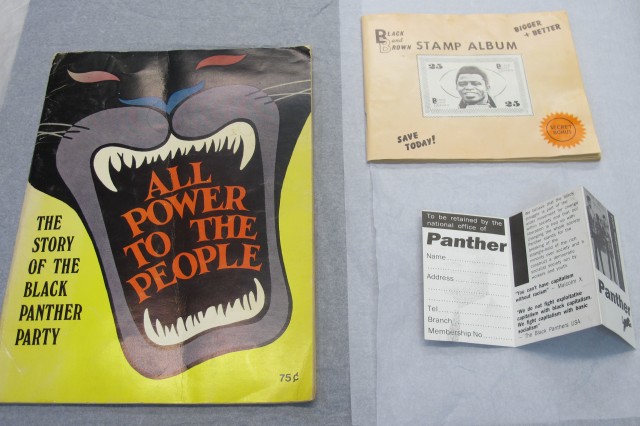

A collection of James Brown stamps. It’s the equivalent of green-shield stamps, sort of a loyalty scheme which could be used within different black businesses. It was about 400 quid. Most of the figures I have are about £25 or £30, but I was just so blown away by it. Often there are items which you just can’t find any more because they end up getting thrown away.

Let’s talk a little more about the exhibition’s overarching themes. It’s clear that Afro Supa Hero is a heavily stylised show, and an importance part of that stylisation is race. What would you say to people who come with a preconceived idea of what the show will be like?

For me, it’s not a ‘Black’ exhibition. I feel it’s something for everybody to get involved in. That was really what the ’70s was about: this explosion of culture that people found universally cool. Even though it’s politicised and has a racial dynamic through Blaxploitation and the rest of it, the one thing you can’t get away from is the coolness.

You’ve already talked a little bit about your family. How has your own family history has played a part in the development of Afro Supa Hero?

It’s the emphasis on family which connects the whole exhibit. I was trying to get it into Bristol after the V&A [2014], and they said it really needed to have a stronger connection to Bristol. So I went and did some genealogical research, ancestral DNA testing, tracing back to my earliest slave ancestor on my Dad’s side in Barbados. The oldest person I’ve traced back to is John Isaac Daniel in Barbados. I also found out about these two brothers, John and Thomas Daniel, based in London and Bristol, who were among the biggest slave-holders in the Caribbean at that time. So you can probably make the assumption that my surname came from them. I went back to Bristol and told them I’d got the connection. And they were like: “Brilliant, that’s great.”

Pretty subjective use of the term brilliant.

Right! They put me in touch with the woman I was meant to be working with. She contacted me and said: “There’s something I need to confess” – she was a direct descendent of Thomas Daniel. So you had this amazing premise, where potentially this show in Bristol would have been [curated by] the ancestor of the slave owner working with the ancestor of the slave. Unfortunately, it fell through, but it helped to formalise the point of my exhibition – to connect with places that link to my familial history, and to do this digging and to uncover other things beyond the surface of what you see.

So when the opportunity to bring the exhibit to Liverpool came up, I realised how connected Liverpool was to Barbados with regards to slavery. It’s interesting that we are doing it this year; it’s my 50th birthday, it’s the 50th anniversary of Bajan independence, plus the links with Liverpool.

How do those personal touches come through in Afro Supa Hero?

There’s definitely autobiographical touches. I found this picture of the Cleveland family reunion, taken in 1981, and I’ve decided to put it into the exhibition. First time I’ve ever shown it to someone publicly. It’s really spooky actually; the picture has the photographer’s telephone number on it, and the last four digits are 2016. Something about this year, this show feels very right.

The connections between history and fantasy for black comic books and super heroes is really interesting, particularly given the emphasis placed on education – Golden Legacy is one example of this, also you can look at the kind of comics which appeared in magazines such as EBONY Jr! – and you mentioned the first figure you collected being Malcolm X. How does that fluidity between the real and fictional play out in Afro Supa Hero?

We have different sections in the exhibit – real Afro Supa Heroes and invincible Supa Heroes – so we make that distinction. Equally, I have this quote in the exhibit: “Whether it’s the Black Panther, or the real Black Panther Party, just be inspired.” The point is, in dealing with the inequality, that’s why you’re pushing the black historical agenda, because the real heroes have not been celebrated. I believe that you only have to go into history to find stories that are often more powerful than the made-up stories.

Often that connection is direct, so a character like Steel being based on the African American folk hero John Henry.

Yet we live in this world where essentially there is a white archetype of a superhero. My belief is that we’re all African, so this exhibit is something all people can step into; you don’t have to be black to enjoy it.

This is something that affects the comic book universe more generally, but how do you feel about the overwhelming emphasis on black American superheroes or comic book characters?

In part, that is just a reflection of the massive role the US plays in shaping global culture, and America as a country which has been able to capitalise on ideas or cultures very quickly and effectively. I would say that the connection to real life heroes and history is a lot stronger. The impact of affirmative action during the 1970s meant that you do have greater historical representation for black Americans within popular culture.

So going back to stamps, in the US they have a black heritage stamp collection dating back to the 1970s, which show specific figures. [In Britain] it is more abstract [and] not rooted in historical specifics. They are offering that with no sense of irony or shame, as if through presenting abstract images of blackness they have covered black history effectively.

That’s certainly part of the larger public narrative about black history in Britain. You have the Windrush Generation [Caribbean people who arrived in Essex on the SS Empire Windrush in June 1948, marking the beginning of post-war mass migration], and then literally nothing before that.

Yes, or you have slavery, and that’s the problem. The principle of inclusivity is good, but the practise of it often makes it impossible, because the selection criteria is based on who is already well known, and who do the general public most know. And that’s every inequality, whether it’s gender or whatever.

I don’t agree with things like affirmative action necessarily, but sometimes it seems to be the only way. That’s what I love about the 1970s, you have the refinement or formality of the civil rights era, and then suddenly a dynamic explosion – Black Panthers, Afrocentricity, I’m Black and I’m Proud – amazing. You can’t separate the figures of heroes from the context out of which they emerged, and that’s what I find so interesting.

I wanted to ask you about your relationship to Afrofuturism, particularly given your involvement in the upcoming Future/Journeys workshop at Liverpool’s Writing on the Wall Festival.

Yes, its going to be a really great event, on Saturday 21 May at District, in partnership with AfroFutures UK and Next Stop New York.

Would you describe Afro Supa Hero as an Afrofuturist project?

I love everything to do with Afrofuturism, but it doesn’t quite fit for me, in the same way that George Clinton probably doesn’t believe everything he came up and did fits under that label of Afrofuturism.

Is that linked to how intensely personal this project is? Afrofuturism, particularly within the academy, is often seen as a pretty abstract concept.

Yeah. It’s great for it to be included as part of the debate, [but] for me, it’s always been about history, and that’s been my overriding passion or love. Uncovering my own personal history, and more broadly, that of people within the African diaspora. That’s reflected through my Design Week column: it’s not about new up and coming designers, it’s about the old thing; like Chuck Harrison inventing the first plastic trash can. That is genius, why don’t we know about that guy? That’s mindboggling to me. There needs to be that equity of recognition.

That’s something which is so true not only of collectibles but also major archival collections. You mentioned earlier how part of the reason some of these items are so valuable is because of the lack of value placed on them in the first instance. It’s crazy that so many collections have been lost over the years because of that.

Absolutely.

I do a lot of work on Lerone Bennett, Jr., and his collections were almost thrown away by a storage locker company before being picked up by Chicago State University for a few thousand dollars. And this is one of the greatest popular black historians of the 20th century.

Oh my god, why aren’t those things in the Smithsonian? Things like that are heart-breaking to me. I don’t understand, it’s criminal. Something my Dad did is a good example of what we’re talking about. He was in what was called the Negro Theatre Workshop, which is seen as one of the first black theatre companies in the UK. They produced the first all-black production on the BBC. It’s in the Radio Times, I’ve got cuttings of it.

When was this?

1966. But no copy of it exists, it got wiped – someone recorded EastEnders over it or something. You can get some photos, but the actual production is gone. And you just think, unbelievable, you didn’t see the value of stuff like that.

That’s crazy.

Yeah it is. Unfortunately, one of the big reasons why figures such as Super Agent Slade are so valuable now is because people didn’t hold onto them. For me, that’s a huge part of what Afro Supa Hero is about: being able to see the value in these collectibles. We need to hold onto those stories where we can.

Finally, what’s the one item you’d really love to have for your collection?

I don’t even know if it exists anymore, but there is a Shaft in Africa collectible from the third Shaft film which has a staff that opens up and has a communicator inside, or it takes photos or something. That! Who has that? If I could have that in my collection… You know somebody has it somewhere.

Probably Richard Roundtree…

Ha, yeah he might have! That would be amazing. Maybe he just looks at it every once in a while. If I could get that figure it would be the crown jewel, I think.

James West

See Afro Supa Hero at the International Slavery Museum, Liverpool, 13 May to 11 December 2016 – FREE

Follow the show on Twitter @SlaveryMuseum #afrosupahero

See Daniel at the Future/Journeys workshop at Writing on the Wall Festival, Liverpool, Saturday 21 May 2016 at District, in partnership with AfroFutures UK and Next Stop New York

Read more about Daniel on his website and via his articles for Design Week

Images, from top: Exhibition Curator Stephen Carl-Lokko holds action figure of Dave Lister from Red Dwarf; Daniel’s comic book selection; Harriet Tubman, Golden Legacy comics, Vol 2. (© Fitzgerald Publishing Co Ltd .1966-72); Black Panther party pamphlet and membership card and Black and Brown stamp album; Jon Daniel at the International Slavery Museum. All images courtesy of Jon Daniel and National Museums Liverpool