“It’s my dream job, but it’s voluntary”: Trials And Triumphs At The Royal Standard

One of the world’s top artist-led galleries celebrates 10 years — including a summer exhibition with previously exhibited artists Liliane Lijn, David Sherry, Oliver Braid and Pil and Galia Kollectiv and more – in 2016. C. James Fagan looks at the humble origins, many challenges and far-reaching achievements of The Royal Standard and asks: What next?

Want to feel old? Well, The Royal Standard Gallery & Studios turns 10 this year. Saying that, is 10 actually that old? In dog years, yes; yet in terms of the art world that’s still very young. You could consider that The Royal Standard is entering a kind of adolescence; a phase where you grab all that experience as one of the best international independent art groups (as voted by No Soul ForSale at Tate Modern in 2010), and try to figure out what it all means and what you are going to do with it.

Shall we begin with an origin story? According to The Royal Standard’s old guard, it all began in a pub in Toxteth, Liverpool. On learning upon this first venue, it’s not difficult to imagine that the idea of The Royal Standard was born from one of those four-pint-fuelled discussions, amongst Liverpool John Moores art graduates, about the lack of this and that. About how if you had an arts space, if you were in charge, it would be different. You know, those chats which dissipate outside the realm of the public house and in the next day’s hangover.

However, in this case, the artists that congregated around that pub table made sure their impassioned discussions solidified into something more concrete: a contemporary, artist-led gallery space and studio complex in Toxteth that was (crucially) cheap to rent, and would be a magnet for the ambitious, emerging and established artists of the city and from further afield. It succeeded; morphing into a non-profit company, funded in part by Arts Council England, that provided a workshop, experimental project space and residency programme outside a wider set of regular gallery and studio events. As a result, they had to move to a bigger venue in 2008, choosing a wind-swept industrial estate on the city centre and Everton boundary; a location which is both part of the city and yet just on the edge. This is how I discovered The Royal Standard and is the form I’m familiar with, having relocated to the North-West in 2009.

On first visiting The Royal Standard — and Liverpool — in that post-European Capital of Culture flush, the art space seemed to reflect a certain confidence and energy. Confirming the idea I had that Liverpool was a city where people did stuff. That stuff, or what I saw on my first visit, was a piece of live art in which a man squatted wearing high heels in the middle of the gallery space, and we as an audience were allowed to throw lumps of coal at him. Or that’s how I remember it. I can’t quite recall the details, and haven’t been able to track down the artist since; however, the sense of a place where spontaneity happens has always remained.

More fundamentally then, we remember that The Royal Standard has been an important platform for innovative work. As well as exhibiting new artworks by more established British artists such as Susan Philipsz, Marcus Coates and Jamie Shovlin, the space is also a collective of 35 working artists. The studio was always a key element of The Royal Standard’s ethos; as founding member Paul Luckraft and current exhibitions curator at the Zabludowicz Collection, London, recalls.

“Having a studio group at its core is something we built from at the very start”, Luckraft tells me. “That idea of committed artists, working in a variety of modes, but grouped together to offer a sense of critical mass and shared ambition in a city that at the time was thin on high quality platforms.”

From that planted critical mass and shared ambition, successful artists bloomed; such as Northern Art Prize nominees Leo Fitzmaurice, Rosalind Nashashibi and Emily Speed; former Royal Standard directors Dave Evans, Frances Disley (below) and Kevin Hunt who set up their own artist-led space MODEL during Biennial 2014; and rising star Joe Fletcher Orr, who currently runs the tiny but critically-acclaimed Cactus Gallery (pictured, top) from within The Royal Standard Studio. This alumni also includes co-founder and editor of The Double Negative arts criticism magazine, Laura Robertson, and associate director at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Lucy MacDonald.

In this small example you can begin to see the relevance of The Royal Standard within the ecology of the UK’s Northern art scene. Though at times over its 10-year history, it may have appeared to be off the beaten track, a place where “you got to be in the know, you know” (as Regular Show’s protagonist Mordecai would have it). This maybe simple misrepresentation, created by its location always on the edges; equally, this may reflect its independent spirit and its ability to do things differently than Liverpool’s larger, publicly funded institutions, such as FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology) and the Bluecoat. Should it matter if people have perceived it as an insular institution? Well yes; at the very least it denies the work and effort put into it by directors and artists alike.

And what of its position as an arts institution? A 10-year anniversary would be an apt time to look not only at the success of The Royal Standard but to where it goes over the next 10 years. Should it carry on ploughing the same furrow, applying for Grants for the Arts and being operated by a rolling two-year directorship of volunteers? Or should it follow the path of independent arts organisation Project Space Leeds, which transformed in infrastructure, size and reach into The Tetley arts centre. Perhaps there is another way than the expected path of a small artist-led organisation moving onto something bigger, more permanent, and more costly; and perhaps less suited to meeting individual artists’ needs.

The best people to speak to about The Royal Standard’s future are current directors Ellie Barrett, Emma Curd and Ashleigh Owen. Owen describes the difference between the perception of the directorship and the actual responsibilities of the role.

“When people find out your job title”, he laughs, “they immediately think of Maria Balshaw (director of The Whithworth Art Gallery, Manchester) or Sally Tallant (director of Liverpool Biennial). It’s not like that; yesterday I was cleaning out the toilets!”

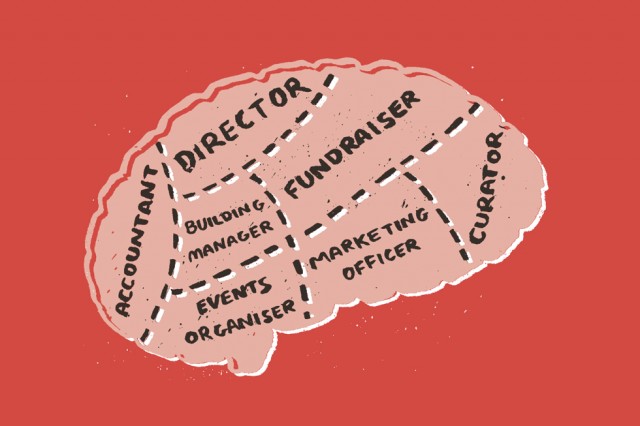

This is a good indication of the realities of working within the art world, especially at this level; a key mid-tier space providing artistic development and cutting-edge programming on a budget. It also displays the kind of dedication this type of role demands: as simultaneous director, marketing officer, building manager, curator, events organiser, accountant, fundraiser, and so on. A role that isn’t set in stone and requires a person to attempt many tasks and responsibilities — roles never considered whilst still studying at university.

“The directorship is so openly defined and difficult to pin down”, fellow director Barrett continues, “because we want it to remain as an overwhelming and completely encompassing experience of the arts sector.”

Still, we might wonder why anyone would want to take on such demanding and unpaid work; yet the enthusiasm Barrett, Curd and Owen share for not only their role but for the arts as a whole is infectious. As Curd puts it: “It’s my dream job, but it’s voluntary”.

These three find themselves halfway through their two-year stint; for the majority of The Royal Standard’s history, it has been run by directors who stay for a minimum term of 24 months; the leaders of what they describe as a “strange organism”. Unlike other arts organisations, The Royal Standard operates as a kind of training ground, allowing each new set of directors the room to shift and mould the direction of the brand. This way of working allows the directors, as Barrett says, to “have the ability to take risks and experiment with the potential of curating.”

Barrett cites her event CLAM JAM, which served as exhibition, performance and discussion about the role of women in art, as an example of this potential of curating, as well as a personal highlight.

This is the condition The Royal Standard has placed itself in: dedicated to independence in a city of large institutions. This makes it become an island of possibility, a Shangri-La for new artists and recent graduates to aim for. Not that The Royal Standard sees itself as a final destination. Recent developments have seen the creation of what might be considered sub-galleries, like the aforementioned Cactus, but also White Wizard, 6 Gins and Muesli (the latter two LJMU graduate projects). Spaces within spaces, where artists and curators seek to exhibit work separately from The Royal Standard. Here we have an ambition to encourage artists to work differently within a larger art organisation, rather than simply use that studio space just to make work; it should be used to create new ways of showing, debating or selling art.

Owen speaks about how The Royal Standard shouldn’t act as a monopoly; rather it should encourage and be challenged by a number of different curatorial projects, hoping that this will create a more challenging and vibrant art scene. Wanting to work differently for the benefit of that scene as a whole is evident when I talk to the directors. When I ask (a rather cliché question) if they had a pot of gold, which artists would they exhibit, they agree that rather than spending heaps of money on “superstar” artists, they would rather see it spent on creating a sustainable space to support new artists to continue to make and show work. To give artists and curators the facilities to do so, whether that’s through exhibitions, residencies or other relevant methods. Also, good heating would be welcome.

But what of the future? The organisation has just officially become an arts charity after much hard work, meaning major changes to the types of funding it can receive. The next 12 months will see The Royal Standard in residence in Temple du Goût, Nantes, France; and welcome Ukrainian resident artists to Liverpool, making work that will form part of the city’s Biennial. Plus, a 10-year special anniversary exhibition is in the making; a kind of greatest hits compilation.

Most thrillingly, another move is planned. Although at the point of writing this article this is ‘whispers on the wind’ [now announced as a new artist-led scheme called Northern Lights, based in the Baltic Triangle -- Ed.], what could a new building mean? On one level, if it was to a larger space, that could mean more artists’ studios and the scope to hold larger exhibitions. If it was further into the city centre, then that could see an increase in the awareness of The Royal Standard and the work it does; more visitors and perhaps more financial stability. Curd is positive about any potential future move. “I have a feeling that in moving, it would make The Royal Standard more current, more exciting, more accessible.”

It’s been strange, attempting to create an overview of an organisation like The Royal Standard. For its very nature is to change: every time a new set of directors takes over, they inherit the successes and failures of the former directors; its style and content is under constant revision, whilst holding onto a core vision of and dedication to high quality artistic development.

It doesn’t mean that The Royal Standard has always been, or will always be, successful in its approach. However, it’s the risk taking that seems most pertinent here; which within this current climate of cuts and devaluing of the arts would seem to be more necessary, more vital than ever. Of course, if you think The Royal Standard isn’t doing the ‘right thing’… well, you could follow their example and start something. Which, by all accounts, they would love to see happen.

Perhaps, then, The Royal Standard’s legacy is to stimulate others to create something, whether that be through inspiration or annoyance. Though it feels strange talking about legacies, as The Royal Standard is still ongoing. Maybe we should think about the organisation more as a continuum; something that is passed on for others to do with as they please.

As always, the only constant is change. The Royal Standard will change — in location, in ideas, in the roles of directors, in the artists it will attract and retain. After all, this is an organisation that once belonged in a Toxteth pub. It is this mutability which defines it: always the same, always different. Or as Curd puts it: “The Royal Standard will always be The Royal Standard.”

C. James Fagan

The Royal Standard Gallery & Studios, Liverpool (Merseyside), UK, 2006 onwards. Celebrate 10 years with a special anniversary exhibition Gettin’ The Heart Ready: showcasing 23 artists, nominated collectively by the organisation’s past and present directors, including Liliane Lijn, David Sherry, Oliver Braid and Pil and Galia Kollectiv. Opening night Friday 29 July 2016, 6-9pm; continues until 11 September 2016

This article has been commissioned by the Contemporary Visual Arts Network North-West (CVAN NW), as part of a regional critical writing development programme funded by Arts Council England — see more here #writecritical

Read it as part of the programme’s book, On Being Curious: New Critical Writing on Contemporary Art From the North-West of England; available as a free e-book HERE (yes, free of charge!)

Images, from top: Harry Meadley’s Level 2 exhibition, at the critically-acclaimed Cactus Gallery (2014), which is based at The Royal Standard; Favela! exhibition (2012); Frances Disley exhibition at White Wizard gallery, housed at The Royal Standard; Clam Jam exhibition (2015), courtesy Sophie Rose Williams; Ane Hjort Guttu: Freedom Requires Free People (2011), as shown in Playing By The Rules exhibition (2016); commissioned illustration of The Royal Standard by Paul McQuay for the On Being Curious book