Fetishism Or Empowerment? Inside Out — Reviewed

Outsider Art is increasingly popular. But what does it mean to be an Outsider Artist, and what are the consequences of such a classification? Jade French visits Castlefield Gallery’s exhibition, Inside Out, in the hope that it will tackle the complexities the genre has become entangled in…

Ironically, Outsider Art is in. Since 1972, when British art historian Roger Cardinal selected the title Outsider Art for his seminal book on art brut, the English synonym has taken on a life of its very own. Used to describe artwork created by people on the margins of art and society, this has historically meant people practising art within institutions like hospitals or asylums; however, the term is now applied more broadly to include those outside the established art scene, such as the self-taught, ’naive’ art makers, artists with disabilities, and children.

Today, Outsider Art is the hot ticket reflected in its dedicated collectors, studios and art fairs — like the Outsider Art Fair held annually in New York and Paris — which draw in large crowds and big bucks across the world. Outsider Art is more popular than anyone could have imagined 40 years ago, but whilst it has grown in popularity, it has also grown increasingly conflicted. For example, the term provokes questions such as: Who is the outsider in Outsider Art? If a trained artist has disabilities or mental health issues, why does this make them ‘outside’ an official contemporary art scene or mainstream peer group? And is this really the way we want to differentiate between creators?

Labelling people as ‘outsiders’ means that the work is often fetishised, and guilty of pathologising difference and diversity. Supporters of the term, however, view it as a potentially empowering label that can offer untraditional artists a commercially viable avenue to create and sell work. With all the debates surrounding the definition of Outsider Art — which usually emerge from academics or arts professionals — I have often wondered how often the artists themselves are supported to articulate their work on their own terms. Are they in danger of being co-opted into an art movement?

A collaborative curatorial effort with artist and academic David Maclagan, Inside Out is Castlefield Gallery’s (Manchester) current showcase of contemporary international Outsider Art. I was curious to see whether the gallery were simply cashing in on the genre’s popularity, or willing to tackle the complexities that Outsider Art is entangled in. I was pleased to see the genre’s increasingly fraught position is hinted at in the exhibition’s gallery text, as so often it is brushed under the proverbial carpet. In short, identified issues centre around the genre’s definition: Who gets to be an Outsider Artist? And what are the consequences of such a classification?

As I explore the exhibition, set across both levels of the gallery, most of the work is exactly what I anticipated from an Outsider Art show. And I don’t necessarily mean that in a negative way. Elaborate, dense and figurative are commonalities of the Outsider Art aesthetic, and demonstrated beautifully in the work of Marlene Steyn, Joel Lorrand and Mehrdad Rashidi.

In particular, Steyn’s hypnotic wall coverings command the lower level of the gallery, adding a much needed punch of chaos into the room. Reproduced from a drawing of ink on paper, the piece, entitled Over the ovaries, dive the divine (2015), is bizarrely reminiscent of Where’s Wally crossed with Frida Kahlo. My eyes frantically wander across the tangle of white female bodies floating on the black background. Breasts, limbs and backsides restricted with peculiar circular structures and the brain goes on overdrive deciphering what it all means.

The works of Jenna Wilkinson, Nick Blinko and Carlo Keshishian share another popular Outsider Art aesthetic, in that they are all created in jaw-dropping detail using astonishingly intricate penmanship. In Keshishian’s case, this translates in taking six years to complete The Void II. As a result of the sheer detail, I find myself exploring the works with a magnifying glass — cleverly provided by the gallery. This interactive action not only encourages the viewer to look more closely — literally examining the work — but it’s also refreshingly memorable. Blinko, who is also the frontman of anarcho-punk band Rudimentary Peni, particularly requires the magnifying glass. His work transports audiences into his uniquely dark and macabre world filled to the brim with skulls, crosses and decaying necropolises.

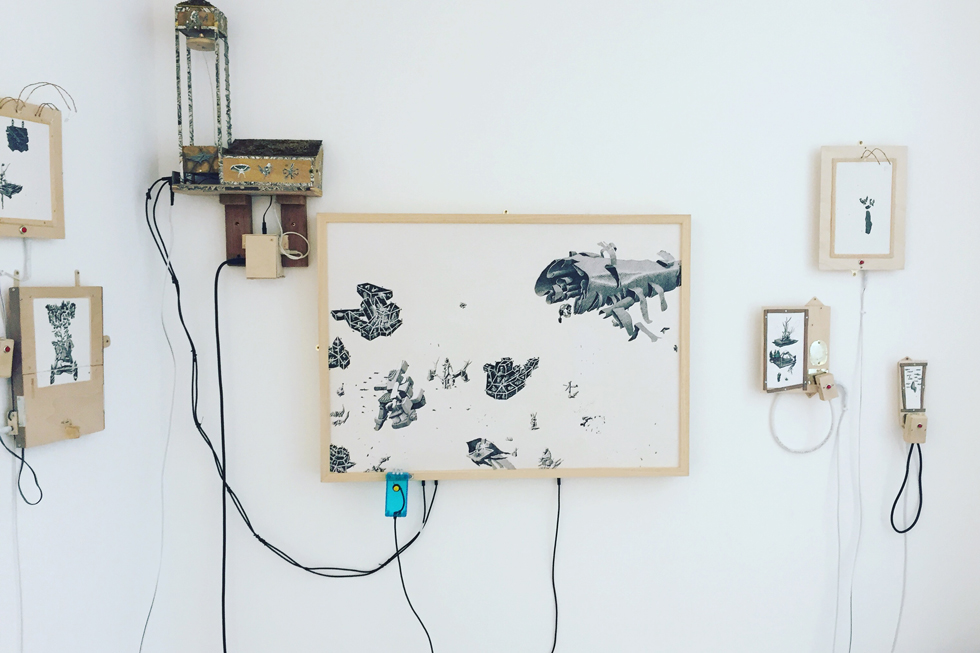

But there are also pieces I was not expecting. There are artworks that surprised me, and it is their inclusion that hints at a fresh and exciting look into Outsider Art; like Darren Brian Adcock’s 2016 series of delicate fine-line pen drawings mounted on wood, caught in the midst of wiring and handmade electronics. On closer look, there are buttons attached to the wires and, once pressed, they emit a vivid blue U.V light. Unexpectedly, the U.V light uncovers intricate under-drawings and a myriad of fine-line pen marks. As I scan the work with the light, a hidden inner world materialises before my eyes, adding exquisite detail and richer narrative to the existing illustrations. There’s something about the electronic quality of the work which, for me, eerily harks back to Outsider Art’s roots in asylums and controversial electroconvulsive therapies. Whilst this piece almost epitomises Outsider Art’s reputation in revealing elaborate private fantasy worlds, it does so using an unexpected and original approach, certainly not one previously seen in Outsider Art contexts.

All in all, a great show. Don’t be put off by the exhibition’s lame and slightly confusing title (on first read, I was unsure if it was related to Pallant House Gallery’s established Outside In project). This exhibition demonstrates brilliantly that the real interest in this work, putting definitions aside, is of an aesthetic of honesty. Whilst, personally, I’ll never fully get on board with a movement based on ‘othering’, it’s impossible to argue that Outsider Art is uniquely arresting, immediate and brave, and always offers a welcome liberation from the conceptual art scene.

Jade French

Jade saw Inside Out between 4 March 2016-24 April 2016 at Castlefield Gallery, Manchester — FREE. The exhibition featured artists Darren Brian Adcock, Nick Blinko, Peter Darach, Andrea Joyce Heimer, Carlo Keshishian, Joel Lorand, David Maclagan, Richard Nie, Mehrdad Rashidi, Mit Senoj, Marlene Steyn, and Jenna Kayleigh Wilkinson

Read about the project opening up a dialogue around mental health via contemporary art – How Are You Feeling? Introducing: Broken Grey Wires