Radical Visions: Claude Parent (1923-2016)

Mike Pinnington reflects on the prolific Supermodernist architect who attempted to achieve the unimaginable: creating convention-defying spaces for climbing, reclining and sliding…

By the time he was approaching his 40s, the architect Claude Parent, who died on Saturday aged 93, had spent time at Le Corbusier’s studio and was becoming commercially successful in his own right. With a number of key commissions already to his name, notably artist André Bloc’s house (essentially a modernist arrangement of elegantly stacked boxes), Parent had demonstrated a flair for creating statement architecture; but, with what you could say was his eureka moment, his work was about to take on more radical proportions.

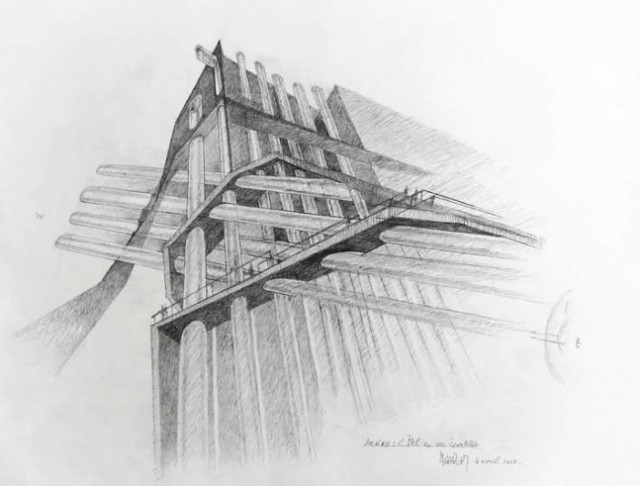

The writer and philosopher Paul Virilio mentioned to him Second World War bunkers, built by the German forces along the Atlantic Wall on a French beach, which had sunk into the ground and become lop-sided, sloping unnaturally. Parent visited the bunkers himself and from then on he rarely looked at, or imagined, architecture in quite the same way. His buildings began to incorporate inclines and slopes where none traditionally should or would be found. To say his work was beginning to defy the conventions of his craft is to put it mildly.

Rather than this resulting in his alienation from his peers and commissions drying up, what might sound to some like flights of fancy started to be found in Parent-designed homes, in industry, and even churches – there was and is a point in there; a method to what appears Parent’s madness.

He and Virilio, having decided that conventions of architecture – straight walls, flat surfaces, working with cubes and rectangles in an accepted fashion – no longer applied to them, founded Fonction Oblique. An architectural principle dominated by slopes and designed to suit the modernist world, it spawned the Architecture Principe manifesto.

But why these unusual inclines and gradients? What was it about them that so captivated Parent, who believed that post-war living necessitated a change from that which had sufficed down the centuries? Ultimately, it was about architecture’s potential to change our understanding and experience of the lived environment and relationship dynamics: speaking in 2010 to 032C magazine (who called him “the last Parisian Supermodernist”), he explained that:

“We’re completely overfurnished. What would it be like on the other hand, if space were understood more playfully, more free, if movement and being in a space also could mean climbing, reclining, sliding?”

For him, it was about changing the dynamic by which we relate with lived environments, other people and the wider world. Or as he put it: “Architecture becomes the medium for staging human relationships.”

In 2014, he was commissioned for Liverpool Biennial, and Parent applied the principles of Fonction Oblique to Tate Liverpool, changing the museum’s Wolfson Gallery into a ‘machine for viewing’ artworks selected from Tate’s collection. The slanted floors and ramps reconfigured the space, providing the audience with an opportunity to experience the gallery anew. His ripping up of the rule book was reflected strongly in works chosen to populate the space: Francis Picabia’s The Fig Leaf (1922), and work by Gustav Metzger, Naum Gabo, Paul Nash and Kurt Schwitters, among others, while his own visionary, often utopian, architectural drawings were selected to appear elsewhere in the gallery. His new vision for the space proved so successful that it was retained beyond the usual three month exhibition run.

His new realisation for the space at Tate Liverpool successfully translated modernism and a particular kind of abstraction in to the gallery, radically revisioning its aesthetic but, more crucially still, impacting on interactions within the space. He had truly delivered on his idea for installing a “machine for viewing” artworks differently, that previously might have seemed impossible, or even unimaginable.

Claude Parent, born 26 February 1923, died 27 February 2016, aged 93

Mike Pinnington

A version of this article appeared originally in Tate Liverpool’s new seasonal publication Compass. Available for £1, exclusively at Tate Liverpool, it features articles and essays exploring exhibitions on each floor of the gallery. Find out more information about Compass here

Read about Claude Parent’s reworking of Tate Liverpool’s ground floor gallery space into a playful mix of expressionistic ramps and ’60s sci-fi set: Biennial 2014: The Space In Between