Inhabiting The Edge: Tricksterism And Radical Liminality

An unassuming Southport beach in the hands of artist David Jacques becomes the battleground for a social and cultural negotiation, finds Les Roberts…

Edges can be many things. They can be sharp (in that they incise or, if blunted, at the very least leave an impression). They can be dangerous (inciting a precipitous gaze or delineating a boundary that is there to be crossed or transgressed). They can be extreme (in that they mark an extremity, be it geographical, experiential or emotional). They can be edgy (a nervous disposition or pushing at the edge of something new). They can, as I said, be many things. What they can’t be, or rather what they shouldn’t be, is centric. That is, they should define a terrain that resists the imposition of a centrist mode of being, thinking or acting. Oxymoronic claims of a ‘radical centre’ – an ‘edgy’ neoliberalism that has not so much eliminated edges as papered over them with territorial panache (a greenback revolution where geometry, like money, is increasingly virtual) – have fallen as flat as the smooth plane of capital that now substitutes for social and public space. If, politically, edges tell us anything (and surely they do) it is that, whether sharp, dangerous, extreme, or edgy, edges need to be valued for what they can enact or perform in the social world. Edges, in other words, matter.

But for all that bluster we should not labour under the misapprehension that edges are necessarily concrete or unambiguously lineal. Edges can also be more contingently drawn, defining an altogether less certain geometry or geography. In this respect they may represent not so much a line as a process: an induction, perhaps? an absorption into a new or reconstituted state of selfhood or consciousness? a transitional moment? a liminal space? All of these have currency in terms of what we might describe as the ‘performativity’ of edges. But what they all speak to more generally is an idea of the edge defined less by what it is than by what those who traverse (or inhabit) it make of it (and from it). An anthropology of edges is thus an enquiry into what they yield and provoke: the social and cultural negotiation of edges as a performative, political, and poetical act.

David Jacques’s short essay film The Dionysians of West Lancs is a work that very much skirts and plays with edges as material and symbolic forms. The physical edge of the land – a beach in Southport on the West Lancashire coast – plays host to the titular Dionysians: early 1990s ravers carving out (having sharpened their edge) a space of reclamation. As an edgeland, the beach no less functions as a space of refusal when set alongside the territorialising centrism of the Tory-drafted Criminal Justice Bill that passed into law in 1994.

A keenly felt sense of enclosure suffuses the film: a long, meditative tracking shot scans an unsettlingly lateral hinterland. Edged suddenly into frame runs the perimeter fence of an installation which, for those trafficking up and down the A565 Southport coast road, remains out of bounds, a thematic refrain that links these latter day geographies to those mapped out historically (the inscription and contestation of edges has a deep and pervasive legacy in these parts). Listen more acutely as you drive down this road and the rhythmic thwack of the fracking drill (the most recent territorial incursion and focus of organised resistance) reawakens, by way of counterpoint, the tribal earth sounds of the Dionysian sand dwellers. Edges beget not just spaces but a deeply-resonant timbre by which we attune and calibrate our positionality, both geographic and political.

Edges also, of course, beget a boast of foot soldiers. These may be baton-wielding agents of the state policing the territorial interests of those for whom the edge ascribes power and legitimacy. They may equally be those who are tactically oriented towards re-drawing or even erasing the edge. The guerrilla assembly of the Southport beach ravers fall into this category. As do those whose resistance to the drainage and enclosure of marsh and common land in late fifteenth-century Sefton precipitated the appointment of so-called ‘Starr watchers’. These were agents of wealthy landowners tasked with preventing the pulling up of Starr and Bent: grasses which had been planted for the express purpose of offsetting the erosion of the sand dunes along the West Lancashire coast, and thus of sustaining legible property boundaries and edges.

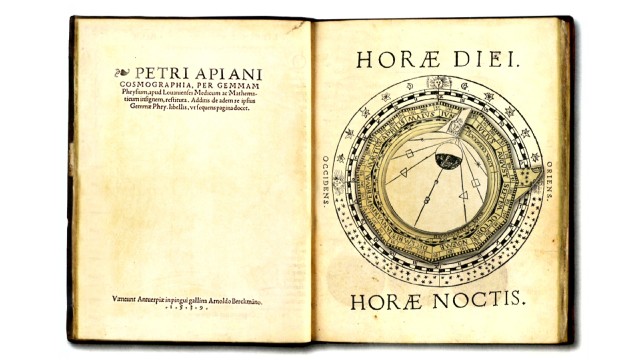

Valued by peasants for its use in the manufacture of mats and besoms, in Jacques’s hands the grass acquires totemic, even talismanic significance. In the same way that it served to cohere and sustain a sense of topographic form, in The Dionysians of West Lancs the grass gives shape to a narrative history that threads together, across time, subjectivities of the marginal and dispossessed: groups, bound by geography if not history, that have found themselves in circumstances where they have been habitually ‘edged out’. Harnessing the alchemical power of Pieter Apian’s Cosmographia (published around the time of the Ince Marsh enclosure), the dissolve between a microscopic image of Marram grass (replete with ‘smiley face’-like cellular features) and the dancers and ravers on the beach conjures the efficacious properties of sympathetic magic.

But insofar as the edge may be looked upon not as a line but a space or zone, it is its constitutive liminality that is of import. It speaks to a space that is on the edge, and hence transacts difference and singularity. It is ‘betwixt and between’ to use the phrase favoured by the anthropologist Victor Turner, whose many writings on liminality made much of the importance of ritual, performance and the potentially transformative properties of liminal spaces. If we can describe those who might populate spaces-in-between as ‘foot soldiers’ (a military metaphor that, while not always apposite, nevertheless heightens the sense of a combative and contentious intent), then it is also worth considering those individuals whose command or intuitive understanding of these spaces is such as to determine their very nature, topography and affectivity.

The performative role of the master of ceremonies can be that of a guide or divinatory tactician (think Special Agent Dale Cooper in Twin Peaks, or a peyote shaman, psychotherapist, Tarkovskyan stalker, or perhaps even rave DJ). Typically imbued with deep local knowledge he or she acts as a kind of ‘ritual elder’, guiding and shepherding the initiates safely through the liminal zone to the ‘other side’. The trickster, on the other hand, is a figure who more purposefully exploits the chaos and ambiguity of liminal spaces and as such embodies potential or actual political power (think Toshiro Mifune’s character in the Kurosawa classic Yojimbo). Like the coyote – the archetypal trickster-beast – the trickster-performer likes to break away from the pack and lay claim to his or her own space (whither others might follow).

By way of illustration, the video footage that bookends The Dionysians of West Lancs documents what is but the flowering of an incipient liminality already set in train by those trickster-tacticians who created the circumstances – the spaces – that made the beach party possible. As with other rave gatherings in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, the event itself grew out of a more diffuse network of liminal spaces such as motorway services which the trickster-cum-organiser tactically exploited to keep one step ahead of the police and to evade the territorialising gaze of the state.

Dancing across, beneath or around the liminal edge, the trickster is also made manifest in the intentionality of the artist. In the case of The Dionysians of West Lancs, Jacques deftly flits between representational spaces (online – textual – archival – performative – automotive – sonic), dragging any carelessly laid edge along with him (confounding, in the process, the rational ordering of a world that in all other respects he has made his own). In the guise of trickster, the artist makes us his complicitous subjects: we follow along pathways that map out a dissonant sense of a territory we can just about discern but no longer truly inhabit. These are lines (not edges) that, yes, tell a story of displacement and dislocation, but also prefigure processes whereby spaces are wrested back or are reconfigured as part of new cartographies of the socio-political body.

To these ends, it is the interpolated voice of Ariadne – a restless web flâneur – to which we need give the final word. Having retreated to the online precincts of a rave chat forum (a rebooted, if incorporeal place of assembly), Ariadne is feeling the need for communitas: for something to take the edge off. “Anybody got any stories?” she asks, “I’m going to have a drive around tonight with my head out of the window listening for some bass”. A moment later, no doubt already cognisant of the prospective lay of the land, she adds: “Anybody got any details or knows of any websites, you know where I am?” By extending the interrogative to the locational clause – “[do] you know where I am?” – the post conveys the ambiguous suggestion that perhaps Adriane herself might not even be sure where she is, as if a narrow circumscription of edges has shrunk and transformed the very fabric of social space.

If Ariadne and her predicament are testament to an anthropology of edges that is predicated on enclosure, then the role of the trickster is to re-animate and re-populate these edgeland spaces, finding within them the powers to enchant and transform. To remain, defiantly, on the edge.

Les Roberts

Watch Les Roberts and David Jacques in conversation

This text forms part of a series of essays, commissioned jointly by In Certain Places and The Double Negative, which has been developed through Practising Place – an ongoing programme of conversations, designed to examine the relationship between art practice and place. Each event is hosted at a different across the country and explores a specific aspect of place by bringing artists together with other researchers who share a common area of interest.

This essay was written by Les Roberts in response to his conversations with artist David Jacques, which began at a Practising Place event in Preston in 2014 and can be viewed online here.

The next event Forms of Inscription: surfaces, patterns and the typography of place is a conversation between artist Joanne Lee and typographer and researcher Paul Wilson, which will take place in Sheffield on Wednesday 17 February 2016. Click here for details.

Practising Place is part of In Certain Places – a programme of artistic interventions and events based in the School of Art, Design and Performance at the University of Central Lancashire. For more information visit www.incertainplaces.org.

David Jacques is a multi-media artist primarily involved with film. His practice engages with the subject of History, its narrative interpretations and the interplay between factual and fictional strategies of representation. His interest in deconstructing and re-apportioning the subject often results in the exploration of forgotten, marginalised and socially / politically disruptive sources. In 2010 he won the Liverpool Art Prize and was shortlisted for the Northern Art Prize. Recent screenings of his work include; Tate Liverpool Art Turning Left, 17th International Video Festival VIDEOMEDEJA, Novi Sad Serbia, WNDX Film Festival, Winnipeg Canada and Sheffield Fringe at BLOC Projects Sheffield. He lives and works in Liverpool.

Les Roberts is Lecturer in Cultural and Media Studies at the University of Liverpool. His research interests and practice fall within the areas of urban cultural studies, cultural memory, and digital spatial humanities. His work explores the intersection between space, place, mobility, and memory with a particular focus on film and popular music cultures. He is author of Film, Mobility and Urban Space: a Cinematic Geography of Liverpool (2012), editor of Mapping Cultures: Place, Practice and Performance (2012) and co-editor of Locating the Moving Image: New Approaches to Film and Place (2013), Liminal Landscapes: Travel, Experience and Spaces In-between (2012), and The City and the Moving Image: Urban Projections (2010).

The Dionysians of West Lancs (2013) is an essay film that weaves through age-old tensions associated with acts of Enclosure and the defence of the Commons. The visual elements of the film include youtube footage of a rave on Southport beach in 1991, animated volvelles (moveable wheel charts or ‘search engines’) from Pieter Apian’s ‘Cosmographia’ published in 1524, and a ‘Phantom ride’ along the Southport Coast Road shot on GoPro from a car dashboard. The narrative is geographically played out around tracts of land running up the coastline of West Lancashire, which have, in recent years, become the proposed sites of ‘Fracking’ and a 42 acre shipping terminus developed by a private consortium. The film engages with the issues of control, ownership, reconfiguration & exploitation of resources associated with this landscape.