Crowdsourcing, Double-Jobbing & Alchemy: Behind The Scenes Of Indie Publishing

What does it take to create a magazine from scratch? Laura Robertson collected some insider secrets — from The Gourmand, The White Review, Dazed and magCulture – at one of the first ever Frieze Academy courses…

I recently attended one of the first Frieze Academy masterclasses, entitled How To Be An Independent Publisher. Co-delivered by Frieze magazine/art fair and journalist/digital expert Alan Rutter of Clever Boxer, the day promised an amazing line up of self-starters: Frieze co-founder Matthew Slotover; Ben Eastham, who is editor and co-founder of The White Review; co-founder and art director of The Gourmand, David Lane; magazine obsessive, magCulture founder and creative director Jeremy Leslie; and Dazed Media Studio’s editorial director Laura Bradley (responsible for Dazed and Confused, AnOther, AnOther Man and NOWNESS).

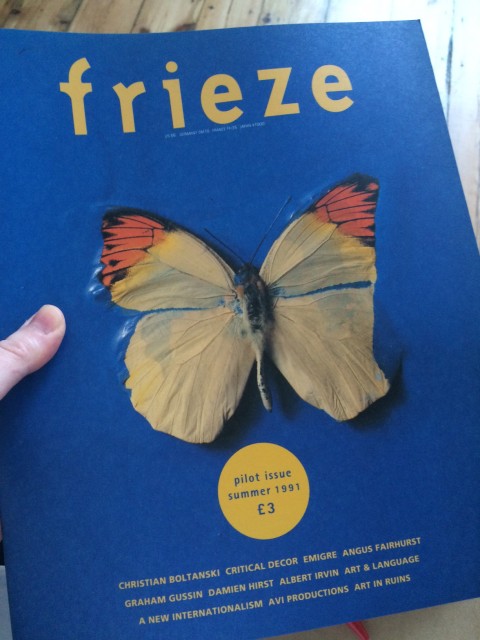

Held at their Rochelle School office in Shoreditch, London, Frieze Academy seems to be a natural progression for the company 25 years on; having run an international magazine since 1991 and whose wider projects now include commissioning, talks and a successful art fair in London and New York.

Aimed at arts professionals, including publishers, gallerists and artists, Frieze Academy’s courses so far have taken a practical slant; editor Jennifer Higgie, for example, on the nuts and bolts of arts writing and pitching, and Sadie Coles and Lisa Panting on the logistics of running a gallery.

With tickets priced at £149 per course, it’s a pricey commitment; I was one of the lucky ones who was granted one of the Frieze Academy bursaries (available for anyone to apply), so only had to pay for my train fare. How could I pass up an opportunity to learn from the best people in publishing?

This day course provoked, for me, many questions about the sustainability of independent publishing, future models and how the sector can change and adapt. This is what I learned:

1. Running a magazine as a business is really bloody difficult

Innovative and well-written content, managing talented people, effective distribution, healthy sales, sponsorship and advertising, funding applications, crowdfunding, trustees, marketing strategies, design needs, print deadlines, mission statements… creating an online or paper magazine from scratch is a unique and hellish task. You have to really, REALLY want to do it. magCulture’s Leslie should know; he grew a blog into a respected online journal, studio, London shop, and global conference programme. Leslie gave a comprehensive rundown of the timeline and logistics of taking an idea to print; it’s exhausting, non-stop, serious business. He also, however, promoted the idea of holding onto the thrill: yes, indie publishing is hard work, but so much fun. Bring a crisp and original idea to the table and stick to your guns: it’s a cliché but you’ll need grit and determination.

2. Editors usually have part-time jobs, no matter how successful they are

Depressing, but true: Eastham is a freelance editor and writer, only running The White Review part-time; Lane has used The Gourmand to set up a successful creative agency, which now pays for the magazine but demands more time. Leslie is an author, tutor, events manager and book store owner. Frieze Art Fair now overtakes the magazine in terms of revenue. So this is where something depressing morphs into hope; the magazine you start can lead to other, sometimes more profitable work. As someone who also writes, edits and teaches as a freelancer alongside running TDN, this was a sobering but also weirdly reassuring moment.

3. Advertisers still prefer print, and no one gets paid properly for the first seven years

The story of Frieze, as told by Matthew Slotover, was infuriating. Coming out of the recession of the 1980s, they received £19,000 per year from Arts Council England for their first 10 years; almost unbelievable to imagine now, due to contemporary constraints on public funding. Frieze magazine attracts big brand, high fashion advertising due to their readership, reach and quality control. However, even with the popularity of reading online (current figures show that 55% of adults use the Internet to read or download content from papers, broadcasters and online-only websites), and despite the enormous potential of global reach, Slotover admits that marketing departments would still prefer to spend £2000 on one full-page print advert than the same amount for one year’s worth of online ads.

And here lies the difficulty for any online platform: no matter what your unique views are like, the tactile, physical form of print will still attract more advertising than your website. And without advertising, you can’t pay for the content you want, unless you have an endless supply of public or charitable funding (yeah right!).

Slotover also discussed the early team; none of the staff were paid “properly” – despite all that funding – for the first seven years; writers were paid £50 per piece and then, slowly, the going rate. Writers, Slotover said, have always been the priority. And shouldn’t they always? A successful print can be a way of paying every contributor for their hard work.

4. You can’t sell something that people can get online for free

But you can’t pay writers unless your magazine makes money. Why should people pay for your new printed magazine, no matter how lovely it is, if they can read the same content online for free? So content has to differ from pixels to print. I immediately thought of the revamped Printed Pages; one of my favourite printed mags, it recently announced that from now on it would be re-publishing selected online content from the last six months. Could that really work? As Eastham put it, if you’re going to pay £15 for a magazine, you’re going to read all of it. But first you have to buy it.

With recent experience in taking Condé Nast and Wired over to iPad, Clever Boxer’s Rutter gave a whirlwind tour of how magazines are diversifying. And it’s not just about viewing via apps or ebooks: The Blizzard, a long-form football magazine, produces a quarterly print and a weekly podcast; Gym Class, a magazine about magazines, simply runs a Tumblr of their favourite magazine front covers as their online offer; and the editor of Offscreen magazine, about creatives who use the Internet and technology, runs a popular warts-and-all blog of how he makes the printed version. Careful consideration is needed to who is reading what and why. Think you know? Ask again.

5. Issue Two is the killer

Slotover planned Issue Zero of Frieze magazine – a restrained 500 copies of a 32 page print, compared to today’s bumper 200-plus page print distributed in its thousands – for two years. They had two months to plan the next issue: a massive jump in time and content management and financial responsibility. Leslie encourages first-time magazine makers to fundraise for the first two issues of their magazine simultaneously, taking some pressure off the finance machine – which, by all accounts, never lets up as soon as you press go. Use a combination of crowdfunding and launch party to sell most of your first issues before they’ve even been printed; get the rest out to distributors as soon as you can. A good motivator for how you want to handle Issue Two is seeing stacks of un-distributed Issue Ones outside your bedroom door; get on your bike and get them out there, or use a subscription service like Dovetail.

Nailing down the first issue’s design should establish a good guide from which to work from; try the awesome Publishing Playbook doc (from the people behind Little White Lies) for some free and (very) detailed advice, useful templates and downloadable resources. Get that first edition right, and creating Issue Two and onwards should become more organised. Which leads us onto…

6. Being shameless: ask the best

Leslie confirmed what we were all thinking: the first issue of your magazine needs to be shit hot. “You’ve got to think: ‘Yep, that’s the best fucking thing I could have done’.” Therefore, ask the best people: the best writers, photographers, designers, illustrators. Make an informed decision on how your front cover looks next to the other culture magazines on the shelf: it has to have character. Apply visual journalism: the design and edit must be at one; an alchemy of function, words and image.

Asking the best also, of course, applies to content, as Lane confirmed: only the best ideas will do, as their now infamous Hot Dog photoshoot proved by attracting worldwide press. Another example: an interview request to the notoriously private Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party was probably going to be ignored; however, The Gourmand takes food as a conversation starter, and asking him to talk through his favourite BBQ sauce recipes resulted in an open dialogue about revolutionary politics (Bill of Barbecue Rights, Issue #6).

Dazed’s Bradley has risen through the ranks due to a talent for spotting good ideas for the magazine and for the studio’s commercial clients. Integrity, she says, is key, quoting her boss Jefferson Hack: “If you stand for nothing, you’ll fall for anything.”

7. Don’t be scared of alternative business models

See point Number Three. Eastham has taken The White Review from a tiny print paid for by crowdfunding and loans to a registered arts charity that receives Arts Council and Lottery funding and has a board of trustees. They still use crowdfunding, and you can now also donate: rewards vary from your name appearing in the magazine to a psychogeography walk through London with author Will Self. This growth has allowed them to run events around Europe, host a short story prize, and write and edit for many other publications; they’re a trusted brand. Staying small allows certain freedoms, away from dictated content or massive sales teams; but it can also restrict your natural growth as your aims and responsibilities increase.

As Lane says, there’s no one, magic model that works for everyone; he’s found that using The Gourmand magazine to spawn a creative agency “is like an interesting business card that goes all over the world.” Stick to your small dreams of independent publishing and make a quality product; you never know, you could be sitting on the next Gourmand, White Review, Dazed, magCulture or Frieze.

Laura Robertson

Laura attended How To Be An Independent Publisher at Frieze Academy on 23 January 2016. Read more about the course here

Images from top: The White Review; magCulture creative director Jeremy Leslie inside his London store; Issue Zero of Frieze magazine with Damien Hirst’s first interview (1991); The Gourmand’s infamous Hot Dog photoshoot