Katrina Palmer’s The Necropolitan Line — Reviewed

Nothing like the Metropolitan Line we know today: Jack Welsh explores the macabre history behind Katrina Palmer’s interactive exhibition — a contemporary reimagining of the London railway that transported corpses to be buried in the countryside…

In Thomas Hardy’s novel A Pair of Blue Eyes (1872-3), the railway enables a love triangle between two suitors competing for the affections of young Elfride Swancourt. The finale sees both suitors, each suspicious of the other’s motives, travel together by train from London to Cornwall in a bid to win her hand. Unbeknownst to them, they are travelling in the same train as her coffin.

Katrina Palmer’s first institutional commission The Necropolitan Line draws inspiration from the railway to elegiacally address sculptural issues of memorial, objecthood and material encounters.

Palmer’s research-led approach begins at Cross Bones, an unconsecrated burial ground not far from her London residence. The site closed in 1853 after it was deemed that the ground was ‘completely overcharged’ with the bones of prostitutes, children and paupers. It highlighted the issue of finite burial space in London, exacerbated by a population explosion and cholera epidemic. A new solution was proposed: the creation of huge cemeteries outside of the city.

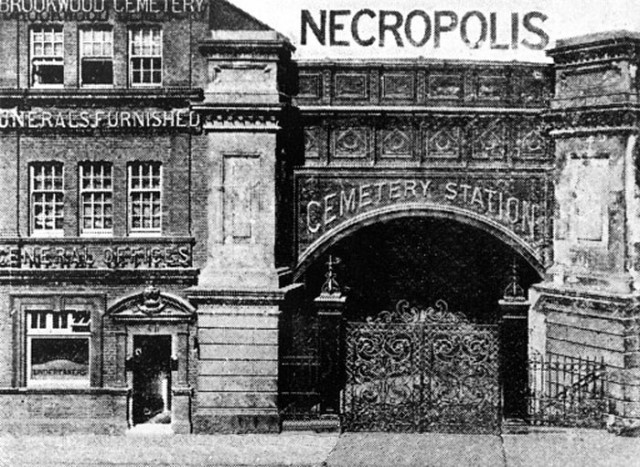

It was envisaged Brookwood Cemetery in Surrey, once the world’s largest, would house London’s dead for centuries. In 1854, The London Necropolis Railway (LNR) opened, a dedicated train line transporting coffins from Waterloo station to their final resting place in Brookwood; mourners were fortunate enough to possess a return ticket. The LNR continued to run as a commercial enterprise until it closed after bomb damage in 1941.

In response to these sites and their histories, Palmer has transformed the Henry Moore Institute into an immersive, ethereal atmosphere bathed in half-light. Within it, Palmer presents several fragmented narratives that blur physical and imagined space, fact and fiction.

Aesthetically, the functional materiality of the railway station is strongly referenced. Two unilateral metal chairs are subtly positioned, with a single newspaper, carefully folded, resting on top. An etching of the layout for Waterloo station (circa 1930s) shows the discreet LNR side entrance.

Most notably, several large light boxes pierce the half-light. Each photograph depicts a trackside signal taken from a moving train; the photographers unknown. Isolated from its traditional context, these grainy, black and white photographs suggest a semiotic resonance beyond the signal’s inconspicuous existence. Silent enablers of a final journey?

On closer inspection, the folded newspaper, The Line, reveals itself as one-issue periodical containing Charles Dickens’ short story, The Signalman (1866), and several articles by Palmer. Referencing contemporary media consumption in format and distribution, the free sheet is a vehicle for Palmer’s lyrical prose and recognisable literary tropes of charged sexuality and visceral and emotive language.

The set piece of the show is a scale facsimile of a station platform horizontally cutting across the second gallery. Complete with grey flagstones, more metal chairs and, of course, the yellow line, it cleverly employs negative space to fuel the imagination; doorways suggestively become tunnel entrances and a track forms in the mind’s eye. The act of ascending the ramp to reach the platform is performative; by doing so, you step onto Palmer’s stage.

Threading everything together is a series of tinny, audio announcements delivered via several grey plastic tannoys. Palmer, in the guise of the Announcer, punctuates the atmospheric silence by reading extracts from The Line and the imagined journey through Cross Bones and the LNR. Palmer’s automated and fragmented delivery, complete with unsettling bursts of an electronic pipe organ, juxtaposes the corporate façade of train operators with the ritualism of the Western funeral ceremony. At one stage, we’re blankly informed: “We’re sorry for being sorry.”

Inevitably, Palmer’s experiential framework will connect with viewers on differing levels. Rachel Whiteread’s sculptural works suggest absence through the reversal of form executed in dialogue with sculptural traditions. Palmer, who is more aligned with Lawrence Weiner’s position that language is a material for construction, uses writing to craft a visceral mediation on loss and absence.

I’m reminded of Susan Philipsz’s site-specific installation Study for Strings (2012) that reverberated isolated elements of score by composer Pavel Haas, who perished in the Holocaust, through the tannoy of Kassel Hauptbahnhof station. Palmer’s interventions are more open-ended, and, as with her Artangel commission End Matter (2015), it’s her phenomenological approach that provides the tension within this constructed liminal space.

The phrase ‘third class coffin ticket’ is a highly affecting example of language. This simple image of a paper ticket stub succeeds in articulating class structures, the corporeal reality of death, and the capitalist framework in which death, as a business, operates. Crucially, it links back to Cross Bones and the injustice of the mass grave.

While End Matter concerned itself with the material properties of Portland Stone and sculptural memorials, here Palmer suggests that the act of memorial is itself a humanistic activity; that stories and words are powerful — and sculptural — forms of remembrance. The end of Hardy’s novel threaded together the everyday banality of train travel and, ultimately, our own inevitable deaths. This is the simple, haunting premise of The Necropolitan Line: the fragility of life and memory.

However, my reading of Palmer’s evocative lyricism is jolted, and compounded, by an unexpected turn of events.

Demounting the platform into the final gallery, I notice an open industrial lift. Brightly lit and out of place, it’s clearly the gallery goods lift used for transporting artwork… but has it been left open by mistake? Surely not? I spot a pair of headphones inside and cautiously investigate.

As I enter, a shrieking whistle tears the funereal atmosphere. I stop dead in my tracks and spin around to see the previously inconspicuous invigilator walking towards the lift, whistle in hand. He closes the door, informing me we’re heading down. I am invited to listen to the headphones; I pick them up.

Clearly, the lift isn’t moving, but he diligently adopts the role of conductor. It’s a peculiar suspense. The headphones rattle out Bette Midler and Peggy Lee’s renditions of Is That All There Is?. I catch a line on the ‘disappointment of death.’ After a minute or so, he pivots, cranking open the adjacent lift door.

I’m promptly ushered out into an alleyway; the metal door jars shut behind me.

I stand outside — alone — in the pissing Yorkshire rain. I’m shocked but also captivated. My mind whirls; my visit has been terminated against my will.

Gone before my time.

Brutal.

Jack Welsh

See Katrina Palmer’s first institutional commission The Necropolitan Line at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds, until 21 February 2016

Galleries open Tuesday-Sunday, 11am – 5.30pm