“Artists who don’t paint aren’t artists”: Top Five Artists’ Manifestos Of All Time

As Walter & Zoniel unveil their new manifesto, we take a look at how artist declarations have been inventing — and destroying — art movements since the 1900s…

‘The artists manifesto’, noted Alex Danchev, author of 100 Artists’ Manifestos (2011, Penguin), ‘is a passport to modernity. To goddamned modernity. / And then to post-modernity. To poor, put-upon post-modernity. / And beyond.’

It seems a new manifesto, by London-based artist duo Walter Hugo & Zoniel, is a passport that ‘beyond’: to a wider discussion about making art. Entitled Formationism, and launched at their current group exhibition Fragments Of… (London), it declares: ‘The production of serious modern art ought to attend equally to ideology and execution’; acknowledging the tension between theory and practice, and listing actions that include encouraging confidence in artists, and engaging with art on ‘a sensorial basis’.

But what does it have in common with other, great artists’ manifestos? Here, we choose five of our favourites…

![F. T. Marinetti, Air Raid (n. 67) (Bombardamento aereo [n. 67]), 1915–16 (detail)](http://www.thedoublenegative.co.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/futurism_words_in_freedom_marinetti_air_raid-640x302.jpg)

1) F. T. Marinetti: The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism (1909)

The Futurists had a great artists’ manifesto. In fact it was the first; The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism, written and championed by charismatic madman F. T. Marinetti (1876-1944), not only inspired the artists’ manifesto as we know it today, but also spawned at least 27 more Futurist manifestos — defined and evolving what the movement stood for — through until 1933, long after the movement had fizzled out.

Futurism was obsessed with new ideas, and it intended to provoke and shock a dormant public into action. Marinetti — a poet, philosopher, novelist, playwright and propoganist — wanted to tear down and destroy all the old ways and traditions of art. Quite literally, in fact; included in his hot-blooded manifesto of 1909 — which was published on the front page of Italy’s largest newspaper, Le Figaro — was a call to ‘to smash down the mysterious doors of the Impossible’ and ‘destroy museums, libraries, academies of any sort’:

‘We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke; bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives; adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon; deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing; and the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.’

The Futurists’ love of machinery and wish for mechanical warfare came true with a great irony: World War I began 28 July 1914, killing many of the artists in the movement. In Umberto Boccioni’s The Charge of The Lancers (1915), the Futurist pits the brute strength of the horse over man-made weapons; eerily predicting Boccioni’s own death just one year later — having been trampled by a horse.

2) Valentine de Saint-Point: Futurist Manifesto of Lust (1913)

The Manifesto of Futurism also declared a ‘scorn for woman’; which is why Valentine de Saint-Point’s (1875-1953) manifesto can be seen as a complex rebuttal. A female Futurist, activist, performance artist, dancer, writer, and artists’ model, she met Marinetti in 1905 and decided to write her own, rebellious response to the movement in a Manifesto of Futurist Woman (1912). Although stating that ‘Futurism is right’ and that ‘Feminism is a political error’, the message seems to say that men are in charge of war, but women, although equal to men, are also in charge of men. It is a show of strength by a woman within a sexist movement, during complex, violent times.

After public readings — guarded and supported by Marinetti and other male Futurist artists — de Saint-Point published her follow up the next year, the Manifesto of Lust, under the banner: ART AND WAR ARE THE GREAT MANIFESTATIONS OF SENSUALITY; LUST IS THEIR FLOWER’…. attacking sentimentality and ‘all the histrionics of love’:

‘We must strip lust of all the sentimental veils that disfigure it. These veils were thrown over it out of mere cowardice, because smug sentimentality is so satisfying. Sentimentality is comfortable and therefore demeaning.

‘In one who is young and healthy, when lust clashes with sentimentality, lust is victorious. Sentiment is a creature of fashion, lust is eternal. Lust triumphs, because it is the joyous exaltation that drives one beyond oneself, the delight in posession and domination, the perpetual victory from which the perpetual battle is born anew, the headiest and surest intoxication of conquest. And as this certain conquest is temporary, it must be constantly won anew.

‘Lust is a force, in that it refines the spirit by bringing to white heat the excitement of the flesh. The spirit burns bright and clear from a healthy, strong flesh, purified in the embrace. Only the weak and sick sink into the mire and are diminished. And lust is a force in that it kills the weak and exalts the strong, aiding natural selection.’

3) Tristan Tzara: Dada Manifesto (1918)

‘DADA MEANS NOTHING…’ how to surpass Futurism? By completely replacing it, of course; artists’ manifestos came to mean the usurping of preceding ideas, in thanks partly to Dadaist Tristan Tzara (1896-1963). A Romanian poet who moved to Zurich to study philosophy in 1915, Tzara created a movement that rejected the Futurists’ love of war — including what they saw as the root cause: the logic of bourgeoisie capitalist society — whilst borrowing liberal amounts of Futurist ideas that had worked well — namely using riotous public performance to spread their message. Tzara proclaims his protest as ‘DADAIST DISGUST’:

‘A protest with the fists of its whole being engaged in destructive action: Dada; knowledge of all the means rejected up until now by the shamefaced sex of comfortable compromise and good manners: DADA; abolition of logic, which is the dance of those impotent to create: DADA; of every social hierarchy and equation set up for the sake of values by our valets: DADA: every object, all objects, sentiments, obscurities, apparitions and the precise clash of parallel lines are weapons for the fight: DADA; abolition of memory: Dada; abolition of archaeology: DADA; abolition of prophets: DADA; abolition of the future.’

Perhaps the most famous artist to come out of Dadaism was Marcel Duchamp, who saw manufactured objects — which he called ‘readymades’ – as potential pieces of art; influencing generations of artists to come, including Robert Rauschenberg and Claes Oldenburg.

4) Claes Oldenburg: I Am for an Art (1961)

Making unusual performances with sculptural props in the 1950s, alongside artists Jim Dine, Red Grooms, and Allan Kaprow, Claes Oldenburg (b. 1929) came to prominence by making huge sculptures of everyday objects — made amusing by their size and soft materials used. His 1961 manifesto I Am for an Art is an ode to Pop Art; originally written in the exhibition catalogue for Environments, Situations, Spaces at at Martha Jackson Gallery (New York), he reflected to the Walker in 2013 that it was made as a call to ‘the possibilities of using anything in one’s surroundings (mostly urban) as a starting point for art’:

‘I am for the art of slightly rotten funeral flowers, hung bloody rabbits and wrinkly yellow chickens, bass drums and tambourines, and plastic phonographs.

I am for the art of abandoned boxes, tied like pharaohs. I am for an art of water tanks and speeding clouds and flapping shades.

I am for US Government Inspected Art, Grade A art, Regular Price art, Yellow Ripe art, Extra Fancy art, Ready-to-Eat art, Best-for-Less art, Ready-to-Cook art, Fully Cleaned art, Spend Less art, Eat Better art, Ham art, pork art, chicken art, tomato art, banana art, apple art, turkey art, cake art, cookie art…’

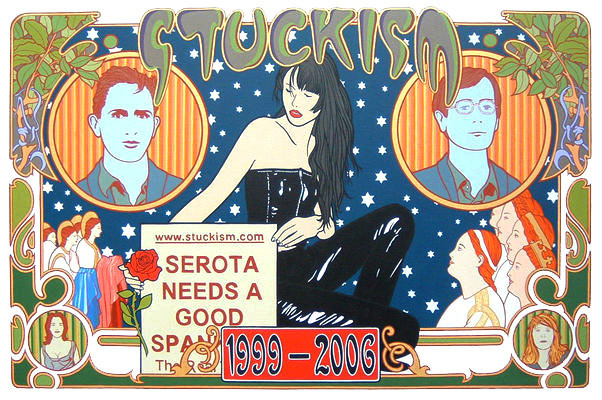

5) Billy Childish and Charles Thomson: The Stuckist Manifesto (1999)

“Your paintings are stuck, you are stuck! Stuck! Stuck! Stuck!” So said Tracey Emin to her former boyfriend Billy Childish (b. 1959). Childish — living up to his name? – produced this rallying cry the same year Emin was shortlisted for the Turner Prize; produced to reject the idea of the Young British Artists (YBAs), including Emin, and their supporters, including Tate director and Turner Prize patron Nicholas Serota. The Stuckist Manifesto (1999) was anti-gimmick, anti-art awards, and — in a sweeping act of contradiction — sought to embrace ‘all that it denounces’.

‘Stuckism is the quest for authenticity… / Stuckism proposes a model of art which is holistic. It is a meeting of the conscious and unconscious, thought and emotion, spiritual and material, private and public. Modernism is a school of fragmentation — one aspect of art is isolated and exaggerated to detriment of the whole. This is a fundamental distortion of the human experience and perpetrates an egocentric lie.

‘Artists who don’t paint aren’t artists. / Art that has to be in a gallery to be art isn’t art. / …The Stuckist is not a career artist but rather an amateur (amare, Latin, to love) who takes risks on the canvas rather than hiding behind ready-made objects (e.g. a dead sheep). The amateur, far from being second to the professional, is at the forefront of experimentation, unencumbered by the need to be seen as infallible. Leaps of human endeavour are made by the intrepid individual, because he/she does not have to protect their status. Unlike the professional, the Stuckist is not afraid to fail.’

Laura Robertson (editor)

Read Announcing A New Manifesto: Formationism (June 2015)

See Fragments Of… at The Blue Factory, Dalston, London until Saturday 17 October 2015, open 10am-7pm. Featuring emerging artists Alison Bignon, Jennifer Abessira, Scarlett Bowman, Jean-François Le Minh, Tristan Pigott and Walter & Zoniel

100 Artists’ Manifestos by Alex Danchev (2011) is available now from Penguin in paperback for £12.99

Images, top to bottom: Fountain 1917, replica 1964 © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2015; F. T. Marinetti, Air Raid (n. 67) (Bombardamento aereo [n. 67]), 1915–16 (detail); Valentine de Saint-Point as photographed by Charles Reutlinger in 1907 © Adrien Sina Collection; Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1950 (replica of 1917 original); Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen: Saw, Sawing, Tokyo International Exhibition Center, Big Sight, Tokyo; Stuckism 1999-2006 by Paul Harvey — Stuckism co-founders, Billy Childish and Charles Thomson (left and right)