Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots And Glenn Ligon: Encounters And Collisions — Reviewed

Ahead of the exhibitions’ closing weekend, Alice Benbow looks again at what Ligon and Pollock — two American artists whose practices are separated by almost 40 years — have to say about the USA, then and now…

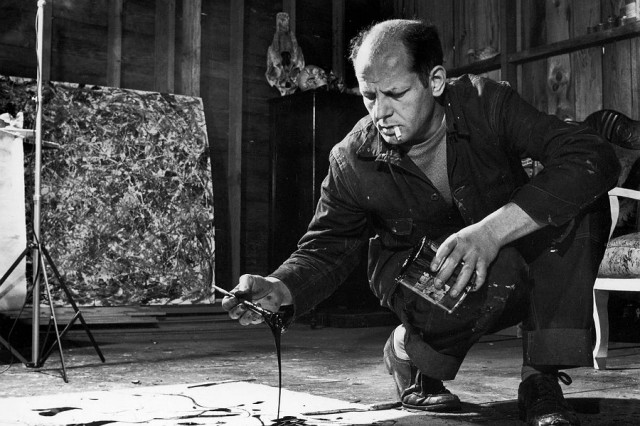

For those familiar with Jackson Pollock, his current Blind Spots exhibition at Tate Liverpool may come as a surprise; exploring, as it does, a largely unknown period in the later stages of the infamous American artist’s life. Born 1912 in Wyoming, Pollock is well-known for inventing a controversial and radical painting technique (dripping paint across huge canvases laid out on the floor), in addition to having a deeply chaotic personal life. Indeed, he earned himself a stand-out reputation in post-war America: a wild variation from notoriety to admiration and excitement – ‘Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?’ (Life Magazine, 1949). This overlooked period in the artist’s life consists of a group of black and white – often ‘black and canvas’ – paintings referred to as his “black pourings”, produced over a very short yet intense two years, from 1951-53.

Pollock shares Tate Liverpool’s fourth floor with a fellow American artist – and admirer – Glenn Ligon. Born in New York in 1960, four years after Pollock’s death, Ligon names American abstract expressionist painters as key influences in his work; including Pollock and also Willem de Kooning (who features in the exhibition). Focussing on both past histories and ongoing ideas (much of the time intrinsically linked), Ligon’s artistic and curatorial interests encapsulate a large variety of ideas, including those of identity, sexuality, race, and America itself, through all of which runs the thread of social concepts and relations. Similarly, Pollock engages — consciously or otherwise — with America as a huge, quickly developing place; his paintings easily capture the immense size and energy.

Strangely neglected for decades in favour of Pollock’s signature, multi-coloured drip paintings – like one of his most famous, Summertime (1948) — the darker (physically and metaphorically), poured works are finally displayed together in magnitude at Tate Liverpool, and are tremendously impressive. With a visible certainty, they reach into and reflect a bleaker time in the artist’s life. Moving away from his more colourful style, during a period of alcoholism and depression, Pollock began to create these ‘black pourings’ following a return to drink after two years sober, and simultaneously seeming to reach a natural point of transition in his work. His return to alcohol coincides with Hans Namuth’s filming of the artist at work – ending abruptly in November 1950 with a dispute between the two.

Upon entry to Blind Spots, we are immediately faced with what appears to be a ‘classic Pollock’ exhibition – the aforementioned Summertime accompanied by Tiger (1949) remind us of the artist we know and love. A few steps further and we reach something wholly different and unfamiliar. Influenced by contemporary artists of the time (such as de Kooning), Pollock was beginning to experiment in black and white – but not quite. Though falling under the ‘black and white’ category in the eyes of many, the artist was in fact venturing even further into the unknown, painting with only black enamel upon bare canvas.

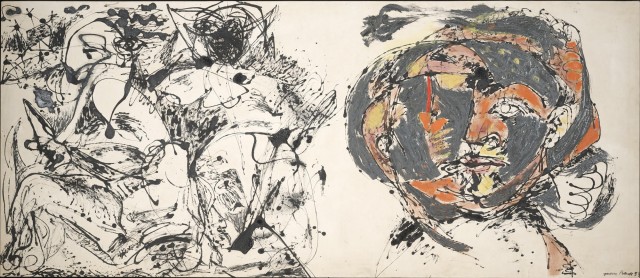

Waiting to be discovered on the other side of the black pourings is Portrait and a Dream (1953), a painting that takes Pollock’s previous explorations and combines them. The canvas is divided into two halves: a gestural, black pouring on the left, and a human face on the right, connected delicately by a thin threadlike line of black paint. Pollock had not yet managed to fully knot together gestural and figurative styles, choosing to paint the two as separate parts on the canvas – a throwback to his earlier Black and White Polyptych (1950).

This painted head is distorted, floating and broken – much like the adjacent ‘Dream’ itself, presented as frantic and chaotic, and an undoubtable reflection of the artist’s state of mind at such a turbulent point in his life as he hopelessly dealt with his own frustration toward his work, problems in his marriage to Lee Krasner, and his alcoholism. Within this work, Pollock somehow retains the dreamlike feel – an untouchable moment of suspension.

The introduction of figurative, more recognisably human portraits makes reference to Pollock’s artistic hero, Picasso; one could almost say Pollock’s homage resembles a Picasso gone wild in the middle of the night. As recalled by his wife in 1969, Pollock exclaimed, “God damn it, that guy missed nothing!”: a reference to the Spanish artist upon whom he both modelled himself on and challenged. Some of Pollock’s paintings (like Portrait and a Dream) incorporate Picasso-like figures; whilst Number 14 (1951) reflects the horror and chaos of Picasso’s earlier painting, Guernica (1937).

At a surface glance, Blind Spots differs hugely from Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions; it is initially quite a shock to walk straight from Pollock’s abstract, expressive, black pourings and immediately be faced with Ligon’s Niggers Ain’t Scared (1996), featuring bold colouration as well as a bold subject matter.

Ligon takes the words of American stand-up comedian Richard Pryor, placing them in a new context drastically far from the mouth of their creator — the vibrant green and blue painting reads: ‘Nothing can scare a nigger after 400 years of this shit’. Dispersing his own work throughout Encounters and Collisions, Ligon aims to create a ‘dialogue’ between artworks and artists, closely reflecting and actively involving American – particularly Black American — history and identity. While Pollock expresses personal difficulties and issues through an abstract style, Ligon’s interest in abstraction – and in particular abstract expressionism – addresses American culture and politics on a wide scale.

In Ligon’s own words, Encounters and Collisions is made up of 10% the curator’s own work ‘and 90% other people’s work’ – including that of Andy Warhol, Cody Noland and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye – and incorporates a variety of mediums including painting, video and museum-like installations – for example, that of Noland’s Pipes in a Basket (1989). A section of Encounters and Collisions is also being displayed here on another floor for a full year, as part of Tate’s DLA Piper Series: Constellations, extending its three month seasonal run.

Returning to the palette of black and white, one Ligon painting features a repeated phrase: I Lost My Voice I Found My Voice (1991). According to the artist, the language he uses here is ‘taken by repetition to abstraction.’ The sentiment of the artwork would appear to reflect the exhibition as a whole: to have a ‘voice’ is to have an identity, and throughout the exhibition Ligon uses his own to challenge the collective American identity – and its views on race, gender and sexuality.

Reaching back to the Civil Rights and Black Liberation movements, the exhibition brings together works to create its very own, poignant, art history. With the current events in America, however (including riots in places such as Ferguson and Baltimore, sparked by lethal police violence towards African-Americans Michael Brown and Freddie Gray), this doesn’t feel so much like history – but modern day reality.

Both the Pollock and Ligon exhibitions cleverly encapsulate America itself: while Pollock captures the sheer size and space of his home country through the scale of his canvases, Ligon addresses and challenges its – and our – preconceived ideas of the USA.

Despite reaching an intense level of fame that coincided with the Life Magazine article, the questioning of existing conventions through the radical establishment of new painting techniques did not immediately work magic for Pollock – particularly in his black pourings. The contemporary view of post-1950 Pollock was one of a man in an alcohol-induced decline abandoning his copyrighted, multi-coloured layers of paint in favour of a darker expressionist and figurative style. It has taken time for Pollock’s more obscure works – the ‘Blind Spots’ themselves – yet curators Gavin Delahunty (Dallas Museum of Art) and Stephanie Straine (Tate Liverpool) have revealed them to be, arguably, the artist’s peak.

Simultaneously, Ligon as a curator draws our attention to blind spots elsewhere. Seamlessly distributing his own art with that of others, he does not present a simple one-sided exhibition, but rather one filled with a complex dialogue between artists, writers, himself, and the audience. While Pollock struggles to embrace his own unique painting style in the room next door, Ligon reaches out to many various mediums – including those used by Pollock himself – to convey an equal variety of truths, thoughts, and concepts.

When leaving Ligon’s Encounters and Collisions, a part of this huge dialogue leaves with you, as does a renewed sense that this is not about history, but issues all too alive and well in America today.

Alice Benbow

This article has been commissioned by the Contemporary Visual Arts Network North West (CVAN NW), as part of a regional critical writing development programme funded by Arts Council England — see more here #writecritical

See Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots and Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions at Tate Liverpool, Fourth Floor, until Sunday 18 October 2015

Images, top to bottom: Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions installation shot, including I Lost My Voice I Found My Voice (1991), © Tate Liverpool, Roger Sinek

Jackson Pollock, 1912-1956 Portrait and a Dream 1953 Oil and enamel on canvas Overall: 58 1/2 x 134 3/4 in. Dallas Museum of Art, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Algur H. Meadows and the Meadows Foundation, Incorporated © Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions installation shot, including Andy Warhol © Tate Liverpool, Roger Sinek

Jackson Pollock pouring paint, courtesy Life Magazine