Hostages, Apollo 17 & The General Election: Modern History Vol. II — Reviewed

Denise Courcoux finds that the second iteration of Lynda Morris’s exhibition is both characteristic and symptomatic of a recent and turbulent history. But can its artists act as ‘moral agents’?

“It is still possible to be an artist who is a moral force in modern history, if you make work about the life of the people in Manchester, Liverpool, Preston, Birkenhead or Cumbria.” Lynda Morris’s guiding premise of art as a moral agent – perhaps an unfashionable concept in contemporary art – is behind her curation of the Modern History trio of exhibitions, showcasing the work of both established and emerging North-West artists in a different guise at each venue.

The series also highlights contemporary art spaces in the region outside of the big cities: The Atkinson in Southport is host to this, the second instalment, with Vol. I having taken place at Blackpool’s Grundy Art Gallery, and Vol. III launching later this month at Bury Art Museum & Sculpture Centre. It’s the mark of a curator who left London in the 1970s to build her career outside the metropolis, notably with the influential EASTinternational open exhibitions which made Norwich a significant pinpoint on the art world map.

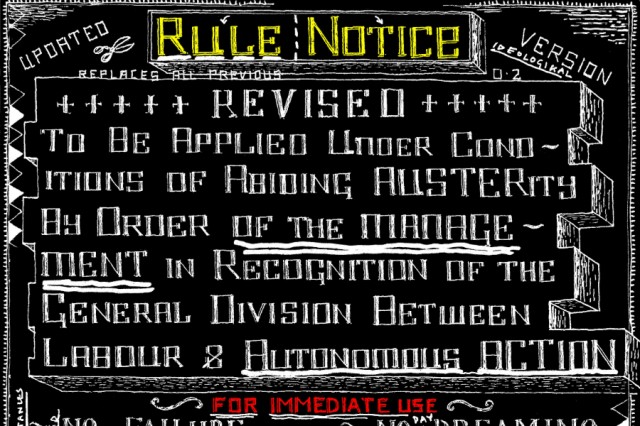

So when does ‘modern history’ begin? The answer given here is 1969: the culmination of a revolutionary decade, the year that humans first set foot on the moon (a landmark acknowledged through contemporary news coverage in Modern History Vol. I), and the starting point for a span of social and political issues explored throughout the works in Modern History Vol. II. David Osbaldeston sets the tone with what he describes as a ‘public declaration’, mounted on a distinctly homemade wooden stand. Originally displayed in Vol. I of the exhibition, it has been updated in light of the General Election results earlier this year. A manifesto of negativity – including ‘No failure’, ‘No idle talk’ and ‘No singing’ – wryly satirises the Conservatives’ ongoing austerity measures.

The Seldom Seen Maps of Stuart Bastik and Maddi Nicholson (Art Gene) cover intensely local territory. These maps chart the coastline of Barrow-in-Furness, borrowing design features of an Ordnance Survey map but filling the landscape with hidden histories and native knowledge, garnered from local communities and organisations such as the National Trust and The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). Fascinating titbits are highlighted, such as the ‘lost medieval village of Alia Lies’ and the Hermit of Sandscale dunes, as well as the best places to spot an abundance of wildlife. It is art with purpose, soon to be made available for sale, where it should fare better than this gallery hang which frustratingly places much of the detail too high up to be seen.

Nina Chua documents a vastly different environment in her film Chongqing Sunset, shot through the window of a train as it passes through a sprawling Chinese cityscape of high-rises, hazy smog and advertising. Against a background of constant chatter, the moving camera stops briefly at a station where a lone commuter touches up her lipstick on the platform, a private and strangely poignant moment of calm in the midst of the modern mega city.

John Davies is also concerned with the urban landscape, showing a series of photographs of the modernist architecture that transformed Britain’s big cities in the mid-20th century. Taken in 2000-2001 and frozen in monochromatic history, they are presented as portraits of failed concrete utopia: Newcastle’s imposing Westgate office block was sponsored for demolition after being voted one of Britain’s 12 ugliest buildings, whilst Birmingham New Street Station – itself voted the second biggest ‘eyesore’ in the UK – is currently undergoing a major redevelopment.

In Tom Ireland’s video work, the day that ‘modern architecture died’ (according to architectural historian Charles Jencks) is played out before our eyes, as the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing project in St. Louis, Missouri is demolished in 1972. Collapse coincides with lift off, as a markedly more triumphant American ending is neatly synchronised alongside: the return home of Apollo 17 from the same year, which marked the conclusion of the United States’ manned missions to the Moon.

Recent Salford graduate Sarah McGurk explores the impact of the Troubles on her childhood growing up in Omagh, Northern Ireland, with miniature models of painted front doors. Each has a distinct identity, representing how individuals nail their colours to the mast through imagery imbued with deep-rooted symbolism. The personal mingles with the political in these small sculptures, with clip-on earrings, press studs and tiny charms masquerading as door furnishings.

Christine Physick’s collages deal with the similarly tribal world of football, specifically Liverpool Football Club and its fans. The sorry state of the terraced houses surrounding Anfield stadium – purchased, condemned and left to ruin by the football club – is well-documented. ‘Tinned up’ houses like these have become shorthand for the poverty and neglect that has blighted areas of Liverpool for decades; here they are overlaid with faded images of flat-capped football fans in the 1960s, some of whom are likely victims of the club they loyally supported. It is a shameful story, which could benefit from being told with some well-aimed anger rather than the mournful nostalgia seen here.

Object-based works reflect the setting of The Atkinson, which holds museum collections as well as its contemporary art programme. A vitrine in the centre of the gallery displays Lubaina Himid’s Lancaster Dinner Suite: a mismatched set of tableware collected from the markets and shops of Lancashire and Cumbria. Closer inspection reveals that the original decorative designs have been reworked to reflect Himid’s ongoing examination of black histories. Traditional English pastoral scenes are overlaid and contrasted with paintings depicting the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, a solemn portrait of an African boy, and a top-hatted stereotype of colonial wealth, alluding to the complexities of trying to remedy centuries of injustice.

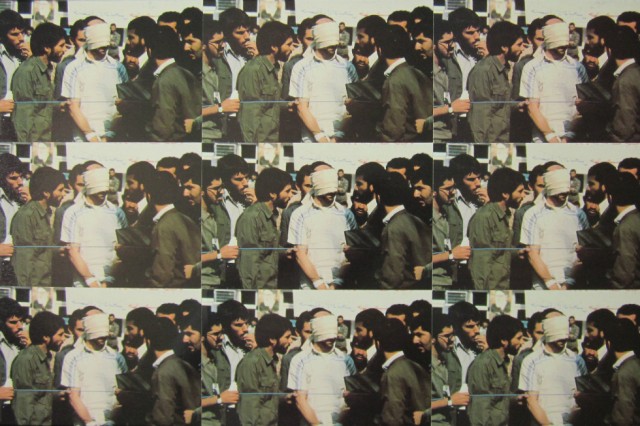

Martin Hamblen is also both artist and collector. His medium is postcards, and particularly multiples of the same card. Hamblen explains: “One is too easy. To collect nine, 16, 25 or more, takes time, patience and commitment.” There is a disparity between the postcard format, more usually associated with holidays, and the repeated hostage scenarios depicted on them here; it leaves us mainly puzzling over what the purpose of the originals could be.

The Modern History Vol. II exhibition also highlights feminist concerns of the past half-century. A selection of Margaret Harrison’s photographs is shown from Women and Work: A Document on the Division of Labour in Industry 1973-1975. The project, a collaboration with Mary Kelly and Kay Hunt, was a survey of the female workforce of a metal box factory in Bermondsey. Undoubtedly a fascinating document of a particular period for women workers – the study followed in the wake of the Equal Pay Act of 1970 – the images are not done justice here. Several of the photographs are too small and dim to make out behind the glass, and the lack of contextual information is frustrating rather than intriguing.

From an established feminist to a recent graduate: Manchester School of Art alumna Natalie Wardle. Her Control Pant Symphony was experiencing technical issues when we visited, but the wonder of the internet came to the rescue. It is a short, smart video of faceless women in ‘shapewear’ (for the uninitiated, these are ultra-tight undergarments designed to reshape women’s figures). As the models adjust their strange flesh-coloured outfits with evident discomfort, the accompanying snapping noises provide a soundtrack to the awkward pursuit of an unachievable body ideal.

Modern History Vol. II, like Vol. I, is pleasingly politicised, and it is refreshing to see artists tackling some of the issues that are both characteristic and symptomatic of recent history. It does though leave a yearning for more work that addresses the unique and critical concerns of today, and their particular effect on this corner of the country; and the question hangs as to how much art as a ‘moral force’ can achieve.

Denise Courcoux

This article has been specially commissioned for The Double Negative by Liverpool John Moores University and Arts Council England. Part of the collaborative #BeACritic campaign — see more here

See Modern History Vol. II at The Atkinson, Southport, until 8 November 2015 — free entry

See Modern History Vol. III at Bury Art Museum & Sculpture Centre from 19 September until 21 November 2015 – free entry

Read Assassination, Space Travel & Regeneration: Modern History Vol. 1 — Reviewed

Images, from top: Tom Ireland, 1972; David Osbaldeston, Rule Notice (2015); Martin Hamblen, Diplomacy (2013). All courtesy the artists, with thanks