A Guide To Pop Art: Paolozzi And The Original Young British Artists

Who really invented Pop Art? Mike Pinnington finds that a group of young British artists, architects and critics — pre-dating Warhol — are to thank for activating a phenomenally successful art movement…

Pop Art: today’s visual culture just wouldn’t be the same without it. But when we think about Pop Art, perhaps the works we most readily associate with the movement are by the likes of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol; American artists whose most famous (in some cases infamous) works have been burned into the post-world-war cultural consciousness.

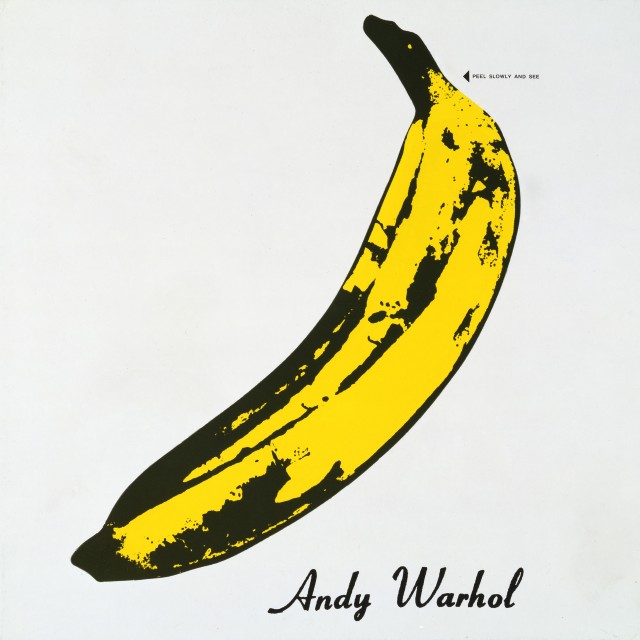

Lichtenstein, borrowing from comic books for his signature style, led Warhol to respond with an even more generic and recognisable item of mass-produced familiarity: the soup can. In keeping with the ethos of Pop, these works (and many more like them) have been reproduced on an industrial scale — I have a postcard of Warhol’s famous Peel Slowly and See banana design for The Velvet Underground and Nico album on my desk, for example.

But as iconic and crucial as the pair might be, in reality the movement’s history predates them both, emerging in a nascent, earlier form, in the 1950s. Implausibly almost, it didn’t even originate in the US. The movement first sprouted and quickly gathered pace with the formation of a radical group of young British artists, writers and critics collectively known as The Independent Group.

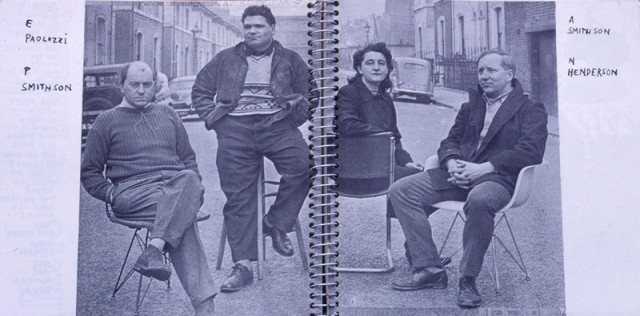

Meeting at the ICA in the early ‘50s, the friends, founded on the principles of challenging the cultural status quo, included artists Richard Hamilton, Nigel Henderson and Sir Eduardo Paolozzi; critics Lawrence Alloway and Rayner Banham; and architects Colin St John Wilson, and Alison and Peter Smithson. They had clear ideas and hypotheses about art and culture — amongst them was that creative production was capable of and almost necessarily had to reflect the cultural landscape from which it emerged.

While it was artists whose works essentially caught the mood, it was the critic Alloway who seems to have as good a claim as anyone on having given the movement its name. In the mid-50s, Alloway had begun to use the term ‘mass popular art’ to describe what this new wave of artists were doing, but come the 1960s — and resonating with Hamilton’s belief that “the artist in twentieth-century urban life is inevitably a consumer of mass culture and potentially a contributor to it” — Alloway attributed the term Pop Art to works that had their origins in the world around them; that is to say, the budding popular culture.

Later, although subject to some dispute, Alloway would personally stake his claim to the term having originated here and with him, saying: “[Pop Art], originated in England by me, as a description of mass communications, especially, but not exclusively, visual ones.”

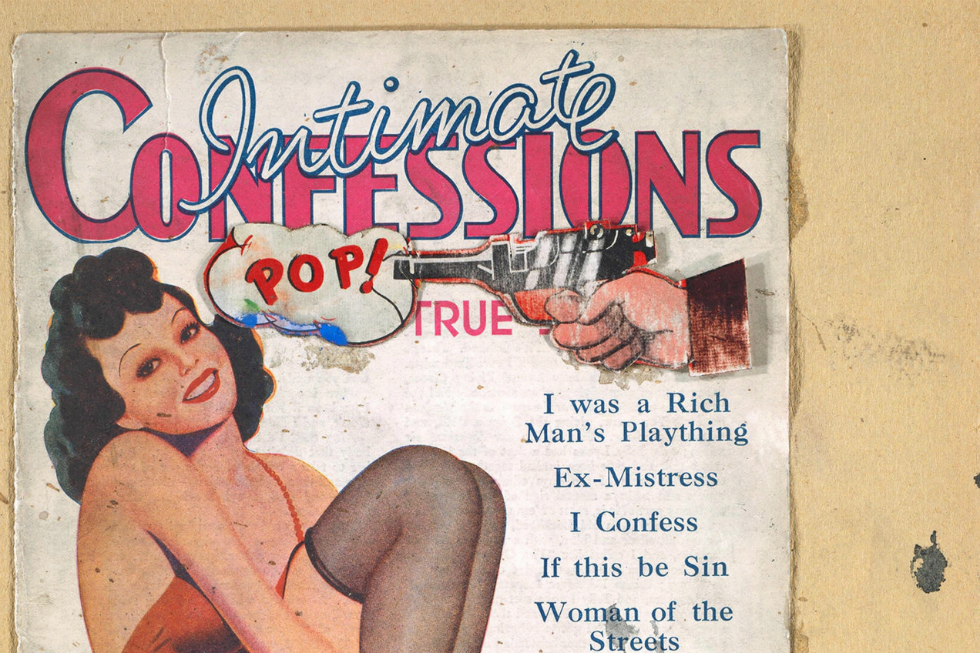

The origins of the term are of course less important than the artworks the movement would birth. An early indication of the prevailing wind in the late 1940s — and containing many of the key concerns of what would come to define much of the make-up of ‘true’ Pop Art — Paolozzi produced a series of collages composed mainly of magazines. They included pin-ups, cartoon characters and imagery taken from ads for US products.

In one, entitled I Was A Rich Man’s Plaything (1947), a gun is accompanied by a comic-book speech bubble emerging from its barrel. In the speech bubble is the word Pop! This particular work makes for an uncanny nod to how the movement would look and also the kind of language – visual and otherwise – that it would come to incorporate and attract. Paolozzi’s investigations with such proto-pop works were indicative of and foreshadowed a coming full-blown fascination with (and dissection of) mass production — both here, and shortly afterwards, in the US.

Alloway would later say: “Movies, science fiction, advertising, pop music. We felt none of the dislike of commercial culture standard among most intellectuals, but accepted it as fact, discussed it in detail, and consumed it enthusiastically.” Of course, implicit in this position is that, for all of those who would embrace the movement, many — quite vociferously — did not. And it continues to be divisive today. Its immediacy, the proclivity toward so-called low culture and its ostensibly throwaway nature, are all avenues regularly explored by Pop Art’s critics.

In the second part in The Double Negative’s series on Pop Art, I’ll argue that the movement, far from being mere pastiche, can, in the right hands, be a powerful vehicle for satire and social comment.

Mike Pinnington

BBC Four Goes Pop: A Week-Long Celebration of Pop Art is featured on BBC Four, Radio and Online until Sunday 30 August 2015 — FREE

Images top to bottom: Sir Eduardo Paolozzi, 1924-2005, I was a Rich Man’s Plaything (1947). Printed papers on card, 359 x 238 mm © The estate of Eduardo Paolozzi. Image courtesy Tate

The Velvet Underground and Nico (1967). Album cover design by Andy Warhol, Collection of The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh © 2014 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York and DACS, London

The Independent Group: from left to right: architect Peter Smithson, artist Eduardo Paolozzi, architect Alison Smithson and artist Nigel Henderson. Image courtesy independentgroup.org.uk

Read Chosen By The Curator: Darren Pih’s Favourite Constellations (including Paolozzi’s BUNK portfolio collages)

See the new DLA Piper Series: Constellations at Tate Liverpool (second floor, ongoing) now — free entry. Open daily 10am-5.50pm