Portrait Of An American Dream: Jackson Pollock & Glenn Ligon Revealed

Tate Liverpool’s summer show re-evaluates the archetypal heroic American artist, finds Laura Robertson; a presentation that wrestles with its tragic past and troubling present…

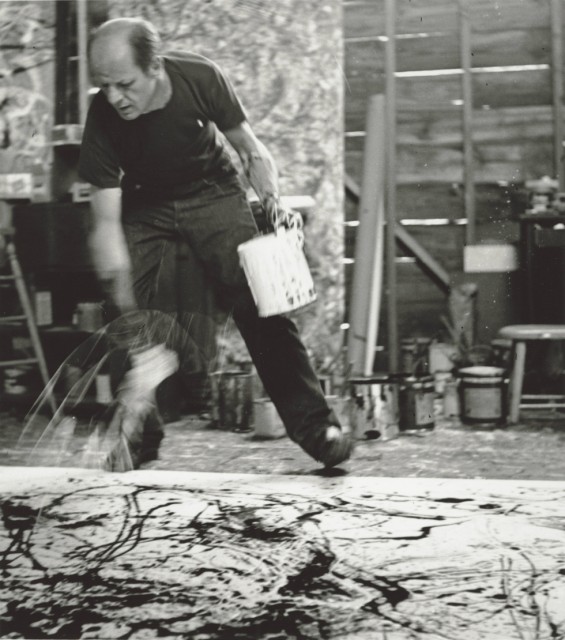

Where is there to go once you’ve reached the top? This, while it is a question few of us mere mortals ever truly have to grapple with, is exactly what faced Jackson Pollock when, in 1949, Life magazine gave him the double-page splash treatment with the accompanying headline: ‘Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?’ It provoked another question, more existential in nature: what next for the pioneer of abstract expressionism?

This is the point of departure for a new exhibition at Tate Liverpool. Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots (curated by Gavin Delahunty and Stephanie Straine), which includes a contextualising gathering of drip paintings he produced in the era broadly considered to be the height of his career (roughly 1948– 50), seeks to explore what he did next. The blind spots to which the exhibition’s title refers focus largely on the relatively neglected body of work that came to be known as the black pourings – painstakingly produced, calligraphic ‘black’ paintings on unprimed canvas. It’s safe to say Pollock critics and fanciers alike weren’t expecting this to follow the lyrical, primary colours evinced in works such as Summertime: Number 9A.

The largest number of these paintings gathered together since their production, they hint at a deeper, more complicated thinker than the one often portrayed through the prism of pop culture, and there’s a step back towards figuration. In Number 14, we can see the debt Pollock owed to Picasso – a man he admired and sought to rival. In Portrait and a Dream, a work the curators consider to be the last significant Pollock effort, it’s certainly not a stretch to read into it the inner turmoil faced by Pollock, by now once again a slave to alcohol.

Alongside these works are examples of Pollock’s wider practice: drawings on beautiful bespoke paper-stock, and probably most surprising for some – certainly less recognisably ‘Pollock’ – are the handful of sculptures interspersed through the show, some of which might better be termed maquettes, which he would never get around to scaling up.

Provocatively, Pollock is paired with Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions, a show which has travelled from Nottingham Contemporary, and shows an artist in thrall earlier in his career to abstract expressionists such as Pollock and Willem de Kooning (as well as overlooked African American artists such as Beauford Delaney). Here, Ligon curates a group exhibition throughout which he has juxtaposed works of his own, thus highlighting the references and influences those encounters and collisions of the title imply. To say it is a timely and poignant grouping of works is an understatement; many deal with the Civil Rights movement and its fall-out, and the exhibition comes at a time when America still wrestles so tragically with questions of race, identity and agency.

The careful and thoughtful staging of these shows points to a highly successful reassessment of Pollock, the archetypal heroic American artist whose career was widely deemed ‘over’ before his death in a car crash (with him at the wheel) in 1956, while Ligon represents the post-war art scene’s legacy (albeit through a very personal framework), shot through with all of the struggle, questions and tentative resolutions that entails.

It gets harder to say new things about the so-called ‘gold standard’ artists, but with this latest edition of its so-called ‘magazine’, Tate Liverpool looks to have done exactly that.

Laura Robertson

See Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots and Glenn Ligon: Encounters and Collisions at Tate Liverpool, Fourth Floor, from 30 June until 18 October 2015

Tickets priced £10/7.50 and include entry to both exhibitions