Picture The Poet — Reviewed

How do you aesthetically capture the poet’s imagination? Leanne Rimmer visits the National Portrait Gallery’s touring exhibition in Preston to find out…

On arrival at the Harris Museum to see Picture the Poet, my initial thoughts are of what to expect – a National Portrait Gallery touring show, it will probably occupy a vast space with variations of photography on contrasting scales. However, I am met with a large dark room, illuminated by a vibrant neon installation. It would seem that Picture the Poet is parallel to (or at the back of?) another show, The Varieties. With one foot in each, the first works I see are the photographs of Madeleine Waller, through eye-battling darkness, a lit up neon installation and the soft glow coming from the exhibition I am here to see. A confusing start.

On entering the smaller-than-expected space, I am faced with a linear display of photography, all in sharp black frames — initially quite an underwhelming experience. A narrative starts with Maud Sutler’s image of Guyanese poet Grace Nichols, accompanied by wall text from Waterpot, a poem from her 1983 book I Is A Long Memoried Woman (London: Karnak House).

Nichols’s gaze is locked with mine. Sutler has captured her strong personality, both in pose and via a contrasting long dark shadow cast over one side of her person. This, in some ways, emulates the Waterpot line the curator has used next to the image: ‘pulling herself together / holding herself like / royal cane’. By establishing a connection between Nichols’s post-colonial background and her words, has Sutler aesthetically captured the poet’s imagination? In a word, yes.

Delving further into the exhibition, I am led around the photographs in their curatorial order, with each image accompanied by wall text. This uniform manner creates a structured journey for the viewer: text first and image second. I am questioning the true nature of actually ‘picturing’ the poet: is the viewer’s true perception of the imagery altered by the text, or does the text simply aid interpretation? The juxtaposition of reading excerpts from the poems and biographical information alongside the portraits causes me to read before I see, and some of the visual reading is lost.

As Picture the Poet travels to different galleries in the UK, it is to be expected that each host venue will put its own stamp on the curation of the show. Here at the Harris, Programmes Manager Sue Latimer has taken the reins. She explained to me that “the Harris was the first venue to use direct quotes from the poet’s poems”. The aim is that viewer is given a range of information to personally choose from; naturally, I read all of it. Reading sections of poetry does add a real sense of intrigue to the artists’ other works not present, challenging you to go away and do some further research. This method of display also provokes you make connections between the visual and the text — it is almost given to you on a plate.

Another observation: a map-like scenario emerges as Picture the Poet travels through a breadth of countries and regions, fitting well with the touring aspect of the show. I wander over to Andy Boag’s representation of Barnsley-born poet and broadcaster Ian McMillan (pictured, above) — a back-page of-a-novel-style headshot, averted gaze over his glasses. I’m pleased to find a bit of northern common ground within the vast array of people and places.

Here is Madeleine Waller again, the first photographer I met coming in from the dark neon installation room. The portraits stand out, being the same scale: three male poets and three female poets, very uniform. Waller’s Jo Shapcott portrait (2006) is accompanied by: ‘What’s the matter? You are right. You are wrong. / Things are going well (badly) Am I disturbing you?’ (Phrase Book (1992)). Shapcott reads in a quite literal way, presenting conflicting emotions and questions, linking to her themes of disrupted places. The gaze captured by Waller is also emotive: holding your eyes and pulling you into the image.

The dark wall and tree bark that Shapcott stands against doesn’t give you an awful lot of information initially, but nature seems to be theme for Waller’s photography; as seen in her portrait of Andrew Motion — set in a garden – and with Owen Sheers (pictured, below). The latter is depicted sat in a field, averted gaze with a dull, grey cloud hanging over him, conveying a sense of emotional pain, and connecting with his subject themes of death and sadness.

We are directed to Sheers’s poem Skirrid Fawr: ‘her weight, the unspoken words / of an unlearned tongue’ (Skirrid Hill, Bridgend: Seren (2005). This line reveals an inner battle, something isn’t complete; ‘her weight’ touches on the personal, and connotes again a loss or a need of comfort or belonging, anchoring the visual interpretation Waller has used.

Waller more than most seems to be using small bouts of knowledge about her subjects to capture them effectively; in a way that the viewer is able to build a narrative around each poet. Commenting on this artist/sitter relationship in a recent interview, Waller confided that “Ultimately I want to make them feel relaxed”, and this is evident in the natural representation she achieves. I am left feeling that Waller has upstaged the rest of the artists.

After a long look at Madeleine Waller, I find myself viewing the exhibition from a distance at the rest of the portraits. By this point, my brain is still processing an abundance of words, images and interpretations; in the second half of the exhibition, the portraits seem to void themselves into a blur.

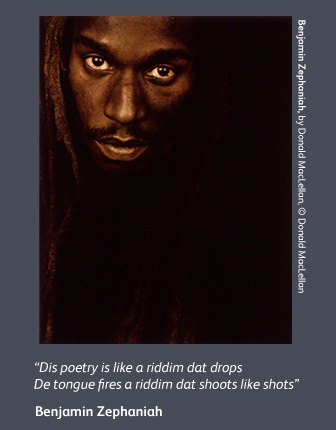

Here is Donald MacLellan’s portrayal of contemporary dub-poet Benjamin Zephaniah (1996) used as the press image for the show. Initially quite striking and somewhat illuminated against the portraits hung either side, and also close to Peter Everard Smith’s portrayal of Poet Laureate Dame Carol Ann Duffy, this seems to be the crowning glory of the entire exhibition.

MacLellan’s portrait of Zephaniah showcases a typical style of his: a warm hue masks the image, and composition focuses on Zephaniah’s eyes. An intense stance that is accompanied with a line from the poem Dis Poetry: ‘Dis poetry is like a riddim dat drops / De tongue fires a riddim dat shoots like shots’ (City Psalms, Newcastle: Bloodaxe,1992). The alliteration creates a rhythm when reading, a beat, an instant embrace.

Zephaniah’s Jamaican heritage is instantly apparent — the grammar inviting you to capture his personal pronunciation – as is the connection between the poet and poem. MacLellan’s visual interpretation expresses Zephaniah’s surrounding passion and politics to great effect. After this, I appear to have come full circle, and arrive back at the starting point of Picture the Poet, and, it seems, saving the best till last with the MacLellan/Zephaniah work.

As I take one last look, I’m left thinking that Picture the Poet offers an intense breadth of information channeled through the camera lens, and plays a kind of aesthetic tennis with the eyes and imagination. The Harris have curated the show really well — stimulating the heart and mind – yet somehow the exhibition still leaves me wanting more. The prestigious National Portrait Gallery collaboration certainly sets up a grand expectation for the entire touring exhibition, one which is not entirely echoed by the Harris. However, the curation here does create an intimate journey with the imagery and words selected.

Poet pictured? I’m still looking.

Leanne Rimmer

This article has been specially commissioned for The Double Negative by Liverpool John Moores University and Arts Council England. Part of the collaborative #BeACritic campaign — see more here

See Picture the Poet at the Harris Museum, Preston until 11 April 2015, and then at The Collection Museum, Lincoln (2 May- 2 August 2015), Sunderland (September 2015) and Carlisle (December 2015)

Picture the Poet is a three-year project in partnership with the National Literacy Trust, the National Portrait Gallery and Apples and Snakes, to support the teaching of creative poetry writing at Key Stages 2 and 3. Working with schools and teachers in six regions, you can find out more about how to take part by emailing erin.barnes@literacytrust.org.uk