On Being Out Of Place: The Artwork Of Rebecca Chesney

As part of our new publishing collaboration with In Certain Places, here art historian Rosemary Shirley discusses the concept of nature and ‘wildness’ — an interest she shares with artist Rebecca Chesney…

According to a formulation by the eminent anthropologist Mary Douglas, dirt can be defined as “matter out of place”. The material properties of that “matter” are in some ways inconsequential, it’s the location which is key. Certain things belong in certain places: crumbs are fine on the plate, but on the floor they become a mess; soil is acceptable in the garden, but in the kitchen it is a health hazard; blood is useful stuff, as long as it stays inside our bodies. Sensitivity to things being in or out of place is a strategy that we use in order to make sense of the world in which we live.

Places and their boundaries, be they bodies, homes, streets or nations, make up our personal geographies and form an often unnoticed background for everyday life. However, it is when things appear in places they should not be — when they transgress these boundaries and become out of place — we notice that we have constructed these apparently strict categories about what belongs where.

Taking a Sunday walk in a nearby wood, I happen upon a pile of rubbish, broken breezeblocks, old carpet, plastic bottles, and a solitary stiletto shoe. I feel unsettled, a little anxious, a little angry. Who dumped this stuff here? At best, they were environmentally irresponsible; at worst criminal, are they still here? And what happened to the other shoe and its wearer…?

While these kinds of objects might not arouse such anxiety in certain urban locations, litter in the countryside feels out of place. It has the power to inflame a set of deeply ingrained binary relationships that define the countryside: litter is man-made in comparison to the landscape, which is seen as ‘natural’; rubbish is dirty, whereas nature is pure; litter is a product of modernity, whereas the rural is timeless; litter is human and the countryside is wild. Suddenly unexamined notions of the countryside are highlighted in neon pink. The countryside is: natural, pure, timeless, empty, and wild.

It may be possible to call this set of ideas an ideology of landscape; they are certainly very powerful in shaping the actions of governments, funding bodies, heritage organisations, discourses around health and well-being, the tourist industry, and — let’s not forget — artists and poets. These last entries on this list, the cultural producers, particularly of the late 18th and early 19th century, were certainly influential in reflecting and consolidating romantic landscape ideals. In the UK, the Lake District was a favourite location for the Romantic poets who explored themes of solitude and wildness, inspired by the dramatic scenery and weather conditions.

Nowadays, the Lake District is in many ways a very different place. In 2013, 15.5 million tourists visited the national park, and it is also home to 41,000 people. However, the park works hard to maintain its image as a place where the wilderness can be explored and experienced, branding itself as one of ‘Britain’s breathing spaces’.

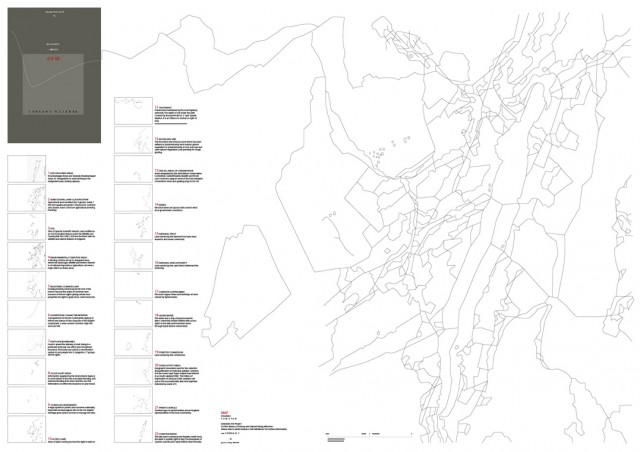

While working with Grizedale Arts in Cumbria, artist Rebecca Chesney set out to interrogate the narrative we are told — and that we tell ourselves — about the wildness of nature, particularly the nature that resides within the boundaries of a national park. After researching over 45 organisations, associations and authorities, all of whom have a stake or interest in the Coniston region of the Lake District, Chesney was able to map out the various ways in which this ‘wild’ location was controlled. These included lines of ownership, local and national governmental regions, areas of special scientific significance, and arts council funding. When all 22 layers of this map are superimposed, the resulting drawing is a web of lines, denoting the invisible boundaries which populate this seemingly empty space.

Much of Chesney’s work investigates our cultural conceptions of landscape and nature, often making us think about plants, animals and people being in and out of place. While in her Lake District mapping project she demonstrated how allegedly wild places were subject to structure, bureaucracy and layers of ownership, she also reverses this process by investigating how our highly-regulated towns and cities might also have their wild sides. The Unofficial Countryside was an idea developed by Richard Mabey in his 1973 book of the same name. The title conveys our tendency to designate certain things, woods, fields, moors, mountains, babbling brooks as belonging to the ‘proper’ countryside; however, when these elements appear elsewhere (for example playing fields, wooded motorway embankments, urban rivers and canals) their potential for wildness and connection to nature can be overlooked.

Exploring decidedly un-picturesque locations such sewage works, rubbish tips and car parks, Mabey mapped the ways in which plants and animals survive and thrive in parallel urban worlds, presenting different a way of experiencing urban environments. Occupying similar territory, Chesney’s projects work to highlight and complicate this perspective.

For the project Unwanted (2006), Chesney conducted detailed plant surveys with the aim of discovering all the weed species growing in Preston’s city centre. Weeds are, of course, defined by their out of placeness, any plant can be a weed if it is in the wrong place. Astonishingly, over 50 different species were recorded growing unnoticed in the inbetween spaces of the city. Bristling out of cracks in the pavement, pushing through guttering and sprouting from chimneys, were unloved botanical delights such as Creeping Buttercup, Nettle, Daisy, Greater Plantain, Creeping Thistle, Herb Robert, Broad-leaved Willowherb, Annual Meadow Grass, Broad-leaved Dock and Dandelion. Chesney recounts that one lovely surprise was discovering a Broad Bean growing in the pavement on Birley Street near the old Post Office building. The resulting exhibition featured specially cultivated examples of 10 of these species, providing an unexpected lushness in the clinical, white cube gallery space.

During a residency in Mumbai, Chesney was inspired by the very specific context of Sanjay Gandhi National Park and extended her investigations to look at the idea, and the disturbing reality, of humans being designated as out of place. This national park is home to many unusual species of plants and animals, but it is also surrounded by extremely densely populated urban settlements. This tension resulted in a ruling by the high court in the 1990s evicting all humans from the park. The ruling applied equally to both temporary residents, who set up in slum villages, and tribal members, who had occupied the area for generations. The total number of human inhabitants of the park was estimated at around 460,000.

The implications of this ruling still resonate today, and Chesney’s project tracks some of the complex results. One piece, a documented conversation, shows how easy it is to illegally purchase and build on plots of land within the national park boundary. Another conversation piece illuminates an unexpected and alarming result of the tension between humans and wild places: a woman from a forest tribe situated with the Sanjay Gandhi National Park recounts how members of her family have been attacked and killed by leopards. The leopards are attracted to human settlements by the abundance of wild dogs that scavenge for food there, and Chesney notes that these dogs are themselves unofficial wildlife — although clearly living in the Park, they are not recorded on any wildlife surveys.

Most recently Chesney has embarked upon an on-going project with In Certain Places called the Invaders Archive. This collection will contain information about invasive plant species and will cover subjects ranging from science and ecology to culture and folklore, human influence and climate change to art and design. Documentation of this project shows the artist wearing a head-to-toe protective suit, face mask and gloves, in order to collect samples from a Giant Hogweed specimen in ‘the wild’. This plant grows to around 20ft tall, embraces impressive cow parsley like blooms, and was once grown in large elegant gardens; however, it has escaped these confines and successfully established itself along the banks of rivers and canals, on wasteland, embankments, parks and cemeteries.

A government website for the management of ‘invasive non-native species’ categorises Giant Hogweed as extremely invasive and warns of burns suffered by people who have come into contact with its sap. These invaders are everywhere: American Signal Crayfish, Japanese Knotweed, American Mink, and certain forms of rhododendron, often occupying the most unassuming locations.

It is both the scientific and cultural process of designating these species as out of place (non-native) and dangerous (invasive) which is so fascinating, pointing as it does, to the otherwise invisible boundaries and their transgressions which texture our understandings of concepts like nature and wildness.

Rosemary Shirley

This text forms part of a series of essays, commissioned jointly by In Certain Places and The Double Negative, which has been developed through Practising Place – a programme of conversations, designed to examine the relationship between art practice and place. Each event is hosted at a different venue in the North of England and explores a specific aspect of place by bringing artists together with other researchers who share a common area of interest.

This essay is part of an ongoing conversation between Rebecca Chesney and Rosemary Shirley, which began at a Practising Place event in Liverpool in October 2013 and can be viewed online here.

The next event In-Between Places: Class, Creativity and Contemporary Art is a conversation between artist William Titley and geographer Steve Millington, which will take place in Manchester on Wednesday 15 April 2015. Click here for details.

Practising Place is part of In Certain Places – a programme of artistic interventions and events, led by Professor Charles Quick and Elaine Speight in the School of Art, Design and Performance at the University of Central Lancashire. For more information visit www.incertainplaces.org.

Rosemary Shirley is a Senior Lecturer in Art History at Manchester School of Art, Manchester Metropolitan University. She is author of the book Rural Modernity, Everyday Life and Visual Culture (Ashgate: July 2015) and she has contributed chapters to the edited collections: Affective Landscapes in Art, Literature and Everyday Life (2015) and Transforming the Countryside (2016). Her research centres on everyday life and visual cultures in historical and contemporary rural contexts. Shirley’s book, Rural Modernity, Everyday Life and Visual Culture, is out now.

Rebecca Chesney is interested in how we perceive land: how we romanticise, translate and define urban and rural spaces. She looks at how politics, ownership, management and commercial value all influence our surroundings, and has made extensive investigations into the impact of human activities on nature and the environment. Exploring the blurred boundaries between science and folklore, her work is also concerned with how our understanding of species is fed by this confused mix of truth and fiction.

Images from top: The Stray Dogs of Mumbai (2013); Map. Volume 1, Coniston, Grizedale Arts, Cumbria (2005/6); Unwanted (2006); The Urban Wilds (2013); The Invaders Archive (2014) — all images courtesy Rebecca Chesney