Chemical Recall: Or, What Is Memory Without Photography?

At the Walker’s latest exhibition, C. James Fagan ponders how images serve as a stimulus for individual recollections of memory and history, and asks: are photography and film actually replacing our real memories?

One of the themes running through the 1982 cult-classic film Blade Runner — bear with me — is what makes us human, and the role memory plays in that concept. The characters, whether they are human or ‘Replicant’, use photographs as proof of their memories and therefore evidence of their existence. In a well-known scene, protagonist Deckard ponders a photograph given to him by Rachel, a Replicant. The photograph was given to Rachel to support an implanted memory, to cement it as ‘real’.

During this scene, he sits in front of a series of family photographs. Facing Deckard is the question: What makes my real memory different to an artificial memory, if they both rely on the production and archiving of imagery?

What is memory without photography?

What is it about the photograph or film, for that matter, that means it plays such a role in the shaping of memories and experience?

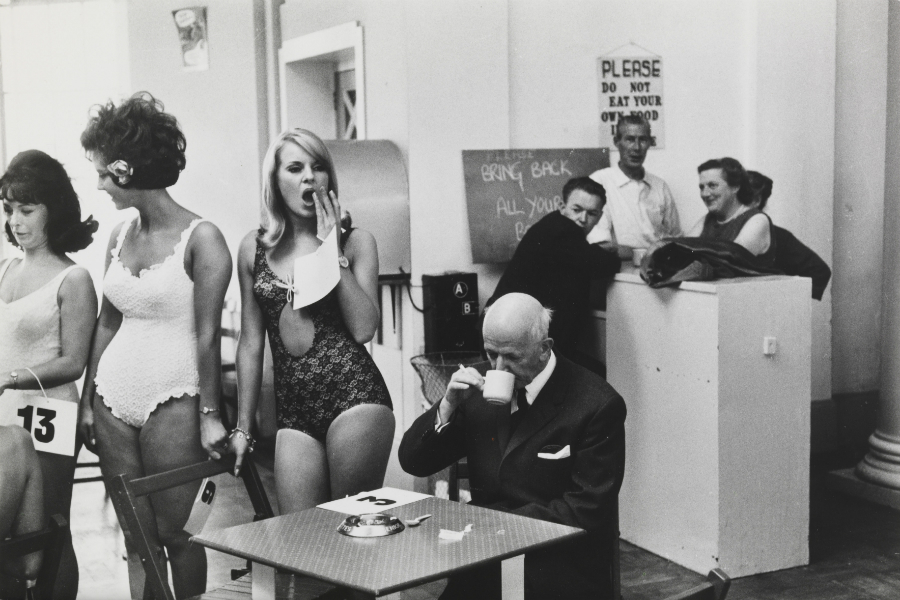

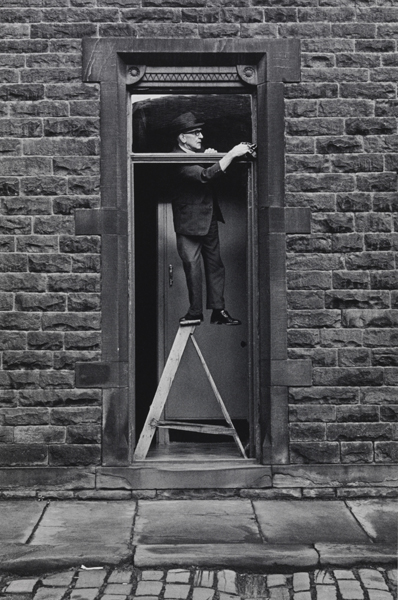

One of the prompts for this contemplation of the photograph and memory was a recent visit to the Only In England exhibition at the Walker Gallery, Liverpool: a collection of work by two photographers, Tony Ray-Jones and Martin Parr, taken during the second half of the 1960s. The exhibition will also form part of this year’s photography festival LOOK/15, which will explore ‘memory’ as part of the event’s wider thematics.

While I was at Only In England, I observed people as much as I looked at the images on walls. It appeared that the images served as a stimulus for individual recollections of memory and history. Not the history of the photograph, or even the subjects within — it seemed that the social and historical context had been replaced by a more personal history.

I wondered: is some mechanism is underway which allows the viewer to use someone else’s photograph to slip into their own history, to position themselves into a parallel history? Which seems contradictory to the idea that a photograph is, in terms of solidifying a moment, an unchanging document. What can be happening to allow this?

It is possible that the photographs are acting as a collective idea of the past. This can also apply to cinema. Not only are they images from the past, but they also become objects of the past. The actual physical properties of the photographs are no more protected from the passing of time then we are.

They become totems of the past.

This idea of the photograph as totem of the past is embedded within its production. Think of the fading edges of an Edwardian portrait, the over saturated colour of a ’50s promo photo, the rounded corners of a ’70s snap. Even the low-resolution of the early digital cameras.

Whatever the process, they create a signature, a shorthand which tells the viewer that this image is the past. Maybe not your past, but a past. Of course, for those who could never experience that past, it becomes the only reference to it.

Film stock becomes the texture of the past, the texture of history. The filter to examine antiquity.

It’s not that either film or photography become a replacement for memory; rather, it moulds and reconfigures our recollections. The writer and artist, Victor Burgin, writes about how this entwining between memory and media occurs in his collection of essays The Remembered Film (2004, Reaktion Books). In this collection, Burgin cites how a number of people recount an event in terms of a film — using the example of a plane attack on a refugee convoy during World War Two.

One would assume that such a life-threatening event would be indelibly marked into the memory and couldn’t be affected by other memories, especially any media influence. However, if you consider that a mediated experience happens simultaneously as real experience, it would appear that the difference isn’t that great.

The memory of the photograph becomes the memory of the event, and the photograph creates a kind of fictionalised memory. So when presented with a photograph, you’re able to slip yourself into this space. It is this aspect of photography which has made it perfect for advertising; you see the trope of people enjoy a product and taking smartphone photos doing so. Every image provides a moment that has been deemed worthy of recording, and creates the idea that the acting of taking a photograph is part of the formation of memory.

Which leads to that new mediator of the photograph, social media. What is the role of the likes of Twitter and Facebook in this complex relationship between image and memory? It would appear that fundamentally the same process is happening, only more so. Pictures are taken as an instant memory, to produce a secondary experience.

Does this mean that future generations will have a ghost experience of parties and country walks?

It might sound like a troubling future, or present, where the role of direct experience has been deflected from memory. But consider that memory is the result of experience; therefore, the photograph is a product of that experience. Before the invention of visual technologies, the most common way of sharing memories was storytelling, often orally.

I have no way of knowing the effect that the oral tradition had on memory and I don’t know anyone who would remember.

This proliferation of imagery in our everyday lives might simply be evidence of the move of our culture from oral to visual traditions of passing information. Like the oral tradition, the bank of images serves as a collective memory, a touchstone where we can share experiences. After all, they are the result of our experiences.

Maybe like the Replicants of Blade Runner, we simply want something definite to point to, so we can say: ‘That was the past, something happened.’

C. James Fagan

Only in England: Photographs by Tony Ray-Jones and Martin Parr continues at the Walker Gallery, Liverpool, until 7 June 2015. Free entry

All images courtesy Tony Ray-Jones and Martin Parr