In Profile: Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960)

“I’m not against the police; I’m just afraid of them”: Adam Scovell analyses one of Hitchcock’s most famous thrillers through the lens of the director’s personal fear of authority…

There is little doubt that Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) is one of the most analysed pieces of western cinema in its long and varied history. By a set of circumstances that seem in many ways to be born of coincidence, it marks a watershed moment where the medium really becomes a new and dangerous art for the masses: where the characters in the narrative are no longer safe; where the music and aesthetics overpower to create an overwhelming horror; and where the Freudian potential so inherent in the form comes to a violent and ultimate head.

In other words, Psycho massages and strangles the ID of Anglo-American cinema out into the open where it can lie in its ugliness and pleasure for all to see.

With Vertigo (1958) topping the most recent edition of Sight & Sound’s once-a-decade Greatest Films Poll, there seems to be some revisionism going on within the film world. Perhaps with the sense of over-analysis and the total normalisation of several of its more famous moments, Psycho seems to have fallen from the general, uncritical favour it used to enjoy.

Recall the infamous shower scene in particular and its shock seems to have diminished; not through the techniques and aesthetics of the scene itself having aged, but because of how fluent society has become in its style and editing. This is why several other murderous scenes — besides the aforementioned shower scene — are far more deserving of attention; the horror of Psycho is more than just a few set pieces, but is a gradual build-up of palpable tension.

The main segment of note for this article (and it is assumed that the reader is more than familiar with the famous, twisting narrative) actually occurs early on, when the faux protagonist, Marion (Janet Leigh) is still alive. In fact, so much of Psycho hinges on creating the illusion that Marion herself is under threat from some unknown force; her enemy is not really Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) and the spirit of his abusive mother, but is in fact fate itself.

When she decides to steal a Texas oil baron’s money, she is allowing fate to control her destiny and hindsight allows a pretty clear image of what her fate is to actually be. After all, Psycho is still a patriarchal film, and opens with the female character enjoying herself sexually; most cases of this relationship in cinema of the dying Hollywood golden age uncomfortably punishes its sexually confident women.

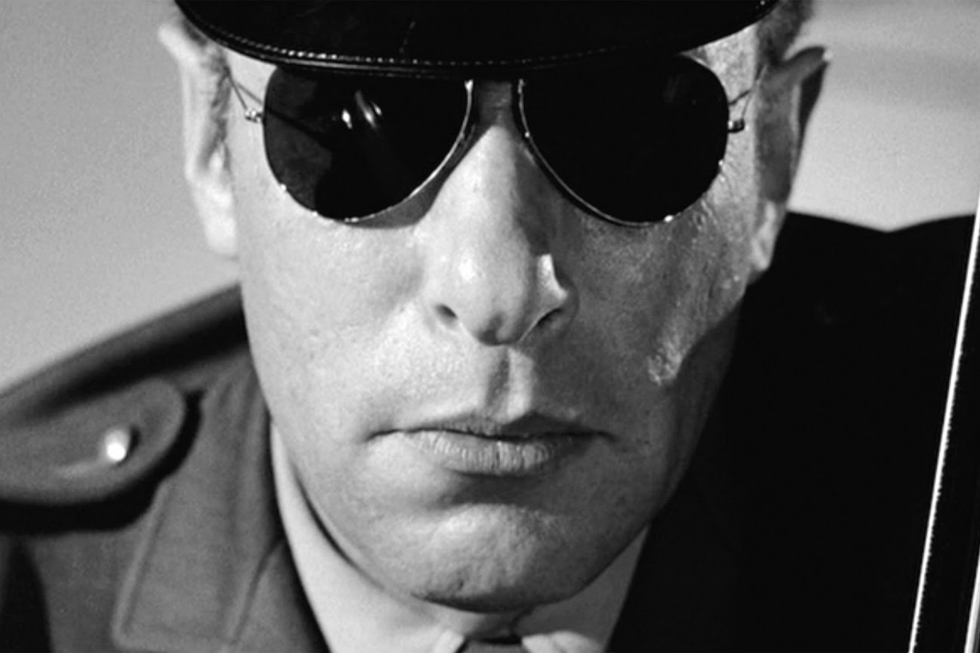

The scene in question, however, is far along from Marion’s initial crime and occurs whilst she is on the road. Having driven all night through fear of being caught, Marion has had to sleep in her car which is parked in a lay-by in the middle of nowhere. She is awoken to the film’s most startling image, of a policeman tapping on her window and looking in. More so than the shower scene or, in fact any scene involving Norman Bates, this is the film’s most unnerving moment for a huge number of reasons.

The first thing to note is the context with which this scene happens. The viewer is already aware of Marion’s situation and knows that the presence of a policeman is a hindrance and not a help. But it is the way that Hitchcock frames him and designs his visual appearance that is most striking. His eyes are hidden by heavy sunglasses, making him devoid of human expression. His soul is hidden by them and he becomes a monotonous cog of a defensive, materialist system. In other words, Hitchcock is presenting the policeman as a danger through his own unknowability. There are reasons behind this that suggests as much about the director as they do about the film.

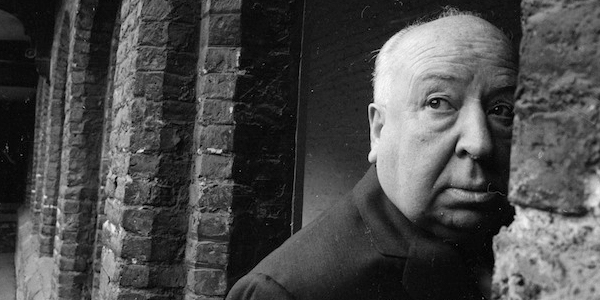

Hitchcock feared policeman and the power of authority they had over the citizen — on the record as saying:”I’m not against the police; I’m just afraid of them”. The oft-quoted story about his father sending him with a note to a police station when younger — in order for him to be locked in the cells for a night, presumably to teach him a lesson — has been linked to the profound sense of paranoia found in many of his films.

When considering his most famous trait, the idea of the wrongly accused man, this becomes even more apparent; the fear is not just of being accused of something falsely but of the actions taken by the authorities when they follow up such accusations. From North by Northwest (1959) to The 39 Steps (1935), the theme almost verges on an obsession for him.

Applying this thinking to the roadside scene in Psycho, and the totality of such a fear becomes an asset. For this is one of the few occasions where the character in question does have something to hide that could potentially lead to arrest and prosecution. It’s almost a mirror inversion of the typical Hitchcock protagonist, which may also explain why Marion is so shockingly killed off in the first third of the film.

However, more so than anything else, this scene captures that sense of paranoia that was gripping America — only Hitchcock was seeing it as a British outsider. Whilst authority was being respected in the era of the Cold War because of a supposed greater “menace”, Hitchcock could plainly see the burgeoning of totalitarianism a system famed for its stance on freedom.

Adam Scovell

Psycho is showing at the Capstone Theatre, Liverpool Hope University, 23 April 2015, 6.30pm. £5 / £15 for a season ticket (all six Capstone Classic films)

Read Capstone Classics: See Indian Culture In A Different Light