Reintroducing Darkness And Mystery Into Lighting Design: Chris Lowe

Lighting designer Chris Lowe tells Elisa Artesero what it’s like creating the UK’s Milan Expo pavilion, his love of Tungsten lamps and Guerrilla Lighting, and why we’re more creative in the dark…

2015 is the International Year of Light, and presumably Chris Lowe’s dream year. As the Senior Lighting Designer at acclaimed international architect and design practice BDP, and one part of Manchester-based design collective Subluminal, he’s an expert in using light creatively and as a way to change our surroundings and experiences. Here he shares with me his work on The Dark Art Movement, his inspirations, and what it’s actually like working at an international architectural firm…

Elisa Artesero: How did you get into the unusual field of lighting design?

Chris Lowe: It’s a bit of a random one, but I think that’s the same with many lighting designers. I’d always been interested in art and architecture but I was also quite good at computing, so I did a degree in Electronic Engineering and Computer Science at Exeter University. It was completely accidental that during post graduation I discovered lighting design, and it’s then I thought “Yeah, I really want to get into this” and researched jobs and companies. It was just luck that at that time an assistant position came up at BDP Manchester and got the job there and have been doing lighting ever since.

So your big break was with BDP. What did that involve?

I came in as a blank slate so I didn’t know any of the technical stuff and had to learn that on the job. I was quite good at visual things so it was a lot of sketching and Photoshopping and creating concept stuff. You have your concept, then your detail design and keep working through stages to build up experience that way. It was hands on learning, really. I also had a great boss at the time, Laura Bayliss, who was a good mentor that came from a Fine Art background. She was leading the lighting team when I joined.

It sounds both creatively and technically challenging. How do you generate ideas?

If it’s an existing site, then going to take measurements and photos, bringing them back and marking things on there. If it’s a new build, then you’ll have 3D images from the architects or interior designers and work with that to start Photoshopping ideas quickly on top and build up from there. Some of the more creative style projects can have more of an existing theme that the client wants tied in to some concepts and you have to tie the lighting in with that idea.

Do clients give you briefs or do you have quite a bit of creative control?

It’s completely different project to project. Sometimes, you’ll have quite a prescriptive, tight brief, like engineering projects, like lighting an office-type space or a train station. Then there are the more creative projects, more completely light art, and you’re free from constraints of British Standards or anything like that. You’ve got a whole spectrum of projects in between those two ends.

Who else do you work with on a day-to-day basis?

I’m leading the lighting team in the Manchester studio and there are three other members. Within the team, everyone’s got their own projects but the Seniors oversee what’s going on and provide guidance and help with the concepts and technicalities of things. It’s a good environment, a team environment where everyone chips in with everything else. If there’s a major deadline for one project we’ll jump on that and work together to get it done. It isn’t just working away in your own little bubble.

Which leads me nicely onto my next question: what design packages do you use?

Photoshop, InDesign, AutoCAD, and Revit, which is a major 3D package that integrates everything into one major model of the building. On that you can do fly-throughs and you can add as much detail as you want. You can make models that are so detailed that you could go through the whole building and order everything for it to arrive on site so it can be built the same. They know exactly how many metres of cables and numbers of plug sockets needed, down to the last detail.

So we use those major packages – plus Dialux, which is a free lighting calculation software actually, that we use quite a lot. That’s basic 3D but you can get a good idea of what light does and it models reflection and interaction with light.

That’s a lot of software! Do you get to be very hands on with the lighting yourself? Or is it mainly done within that computer environment?

It depends on what the style of the project is, so if it’s something more off the wall that we haven’t done before, or something that’s quite different to a standard solution in a particular area, then we always try to get samples in and mock it up. A lot of it just comes from experience, you kind of know that a certain beam angle or a certain lamp will provide a particular effect, so you can estimate a lot of it.

What do you think your duty is as a lighting designer?

That’s an interesting question. I guess in its purest form, it’s to make things look good. To create spaces or environments that people want to spend time in. In addition to that, you have environmental factors to consider because we obviously do a lot of large scale, corporate buildings, so a lot of energy usage comes into that.

I think you have to be quite a visual person to be a lighting designer, obviously, because it’s all about what you can see isn’t it? It’s making spaces interesting. The way I see it is enhancing what’s already there with the design team to create something better.

Can you tell me a bit about The Dark Art Movement?

The Dark Art was started by myself and a colleague, Philip Rafael. It basically came out of a frustration of spending too much time on the engineering style of projects that I mentioned, and lighting a space to just some sort of luminance level or figure that someone, at some time, thought was correct for a space. It can be a bit uniform and boring, so we asked, how can we do this better? How can we create more interesting spaces visually?

From the energy side, and also the biological side, we’re meant to have darkness at night and around 10-50,000 lux during the day, but we live our lives somewhere in the middle, with interior lit spaces that are nothing like being outside, and nothing like being in complete darkness either. So what we’re doing to ourselves is completely unnatural from so many angles.

So, it’s about reintroducing darkness and mystery into lighting design. It’s a cause for debate within the lighting industry because some believe that we need the standards, as without them we would have anarchy. But there’s another school of thought, which is that those standards shouldn’t reduce our capacity for creativity and creating spaces that are interesting. That’s what those symposiums and debates were about. Airing the debate and asking ‘Why do we need to blanket light office spaces?’ People are often more creative in darker spaces than they are in lighter spaces, and a lot of creativity happens at night or evening. So it’s looking at how we naturally evolved and coming back to darker spaces at night and using more natural light in the day in a creative and visually interesting way.

Who joined the symposium? Where was it?

That was in Copenhagen, at a professional lighting design convention held every two years, with about three days of conferences and talks. We had the symposium as part of that and an international panel to discuss these different thoughts, but from a dark art standpoint. We had people from different backgrounds, so the designer from Chile is part of the dark skies movement over there, reducing light pollution so you can see the stars in the cities at night. One panellist from New Zealand came to talk about lighting art in galleries, to show that you can light a piece and that it could be surrounded by almost complete blackness and people don’t die! It’s people sharing experiences from different angles to say that there’s ways of doing things better.

Are you planning another one?

It’s in the very early stages but possibly one in China, this year.

Would you agree that there is too much artificial light in our cities?

Yes. There probably isn’t too much if it’s done in the right way, but the fact that there’s no visual hierarchy and everything is lit to the same blanket level: there are no features, nothing stands out. The problem is that it’s not designed, it’s just kind of happened.

Do you find that you’re constantly switched on (excuse the pun) walking around the city environment, getting irritated by the lights?

[Laughs] I think it used to be worse at first, but now you just become numb to it. But I think the first thing a lighting designer does is to look up and to see what’s installed above them. Places in restaurants and bars, places at night that you want to relax in can be quite frustrating if you think that the lighting could be done so much better. So, yeah, you are aware of it permanently.

What are the common mistakes?

Things being too glary, so things are spot lit at a bad angle and shine in your face. Or when you’re in a dark bar and the brightest thing is the emergency exit signage, which produces a horrible quality of light that’s nothing like daylight.

What’s the most frequent problem that you face when designing with light?

Budget. I think people’s expectations of what you can get but without putting the money in to back it up. Clients don’t always appreciate that it does cost money to get the best quality light, that you need to invest in it and can pay dividends further down the line. I guess the value of it is often underestimated in both financial and aesthetic terms. The biggest obstacle in the whole process is trying to convince someone what you could do and what potential there is.

Who, or what, are your greatest influences?

I really like a lot of what [London-based arts practice] United Visual Artists do; they do a lot of creative stuff that pushes the boundaries of lighting design. I’m also into photography as well, because photography is capturing light.

Have you got a favourite piece of lighting tech?

It’s not new technology, it’s old technology that’s being banned, but I guess a good old Tungsten lamp is probably one of my favourite bits. Just for its simplicity and for the fact that the quality of light that it gives is the best.

Are there any equivalents in new technology that match that quality and effect?

There are many developments with LED technology that try to match it, and it’s coming along all the time, but isn’t quite there yet, or the quality of light and the spectrum isn’t the same as the warm light you get when you dim it down compared to full light.

What are you up to at the moment?

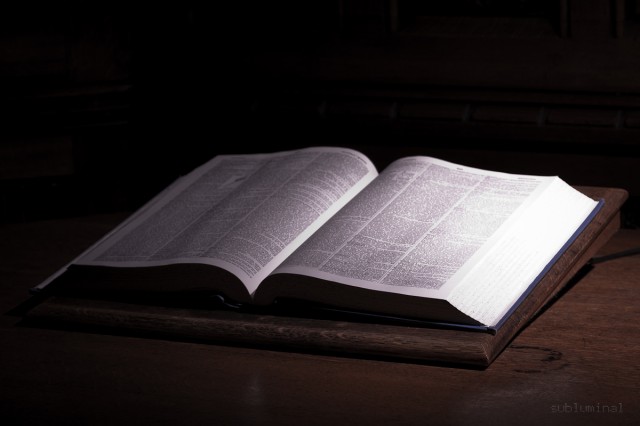

We’re working on Manchester Cathedral. We’re in the early stages of the concept design at the moment, which is really exciting and will be amazing when it’s done. That will be in a few years as these things always take time, particularly in an existing old building, as there are lots of design stages you need to go through. We’re working on the UK Pavilion for Milan Expo (main picture) with an artist called Wolfgang Buttress. There are a lot of interesting projects on at the moment, both in the UK and abroad.

What’s your favourite project so far?

I don’t know if it’s my favourite, but one of the early ones in my career was Guerrilla Lighting. We basically took three sites in Manchester, the best being under the arches in Manchester Castlefield. We did the design for it and we got 80 people with torches and colour filters to come along, got them all to turn them on for 30-40 seconds and then that was it. The transformation of it being unlit and lit was just incredible. I think that was one of the best ones because it was so simple in its idea, but really demonstrated how light can transform a space.

Elisa Artesero

Chris Lowe recently provided a lighting scheme for Manchester Art Gallery with Icelandic collective Myrkraverk for the Enlighten Manchester Festival of Light Art. Elisa Artesero also showcased her first large scale outdoor piece, A Solid Wish Scatters, for the same festival in Piccadilly Gardens

More information on BDP Manchester and Subluminal