“He purposely erased a lot of his own humanity”: Transmitting Andy Warhol

A robotic persona who painted by numbers, anticipated the Internet and annoyed Rauschenberg: Tate Liverpool assistant curator Stephanie Straine gets to grips with Andy Warhol through a major exhibition of his work, and finds that there’s plenty left to say…

First of all, congratulations on Transmitting Andy Warhol. Before seeing the show, I read a great article by Gilda Williams (‘Silver Sliver’, Art Monthly) that made me think differently about his work. In it, she insists that “labelling Warhol a Pop artist lazily avoids the bulk of his prolific output.” Do you agree?

I think it’s an interesting, provocative statement, and it acknowledges the fact that it is really hard to say something new about Warhol… How Williams backs that up was very well reasoned, and included referencing a lot of the content of our show; namely, his experimental film work, and his work with the Velvet Underground, the Exploding Plastic Inevitable (EPI).

He wasn’t a Pop artist for any significant amount of time; I think what we’re doing in Transmitting is looking at the parallel picture of his practice. What we’re calling more of the ‘lateral spread’: his printmaking, painting, going onto film, and then publishing; we’re talking about the fact that Warhol democratises art production. So I don’t think it’s about labelling him Pop or not labelling him Pop; it’s about the simultaneity of it.

What’s interesting is that people say he gave up painting for film; but he didn’t actually do that. It’s actually always held in a balance; at the same time that he’s becoming one of the most famous artists in America, he’s producing essentially underground films, being shown on the underground film circuit; it’s only with Chelsea Girls in 1966 that he starts to show in movie theatres, and even then, it’s not really a commercial success in any meaningful way.

He manages to keep the high and the low together at every point; that’s the idea behind calling the exhibition Transmitting Andy Warhol, as he manages to do this at the same time in different channels of the media.

Warhol was enamoured with experimental filmmaking, despite not being seen as a commercial success as you say. But he always juggled multiple forms of making, didn’t he?

In essence, he finds in 16mm film aspects of his practice that he pushed in painting: the repetition, the monotony, the breaking down of an image, or prolonging of an image to seemingly endless lengths. What you get in the Flowers series is what you also find in the eight hours of the Empire State Building as a static shot; and that’s essentially being made at the same time.

Even, for example, the idea that he was a commercial illustrator and then became successful in the gallery/fine art world has more complexity; he carried on taking commercial commissions throughout the 1960s and indeed right the way through his life. Even when he had solo shows in New York and was getting well known for his paintings, he didn’t stop accepting commissions. There’s a great spread from LIFE magazine in 1965, where you have a fashion shoot with models and they’re projecting his films directly onto their bodies, which I think is a popular/media/ fashion version of what he does in the EPI with the Velvet Underground. So there’s a complete crossover there with a cool, grungy, hip scene and LIFE magazine, which had millions of readers. Complete democratisation.

We’ve got that LIFE magazine edition in the exhibition, which I think is really crucial; you think that he wouldn’t be doing stuff like that anymore, but he is, because he sees the value in it. It was about the multiplicity of forms, for him, and furthering his interest in opening up channels.

Is there anything new to say about Warhol? He’s not even really human anymore: he’s an icon, a brand, a statement.

I think he did that to himself. He purposely erased a lot of his own humanity, even at the point of setting up the Factory and having this amazing set of people around him; adopting this robotic persona, which was very famous.

It is very interesting when you think that he was also adopting this robotic way of making painting; I think there was a merging of his life and art, not in the Robert Rauschenberg sense, but in this kind of post-industrial, reflection of high-capitalist society way. I think that’s the origin of the very early ‘60s works, copying ‘paint by numbers’ sets like the Do it Yourself (Seascape) (1962) which we have in the show. It is erasing any sense of Warhol as the author of the work, as he’s using a general source of paint-by-numbers. He is channelling mass and popular media sources through his work; going into a canvas painting and coming back out again through canvas into something else.

Why do you think he loved Rauschenberg so much?

Rauschenberg together with Jasper Johns have often been called the American father figures of Pop art; they were doing a version of Pop in the 1950s, before the classic period of Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg and Warhol comes along. They completely redefined how you would approach painting, through how they used the idea of the readymade. So, Johns’s Flag and Rauschenberg’s Combines – works where he used a stuffed goat or a tyre, the bedsheet – Warhol wouldn’t have been able to do what he had done if they hadn’t made that work. It’s just not possible. They’re the key to unlocking Warhol’s work, as he moved from being a full-time illustrator to someone who made paintings. He talked about seeing their work in ‘50s New York; I think they’re crucial really.

People don’t always talk about Johns and Rauschenberg being together; although Warhol met them through his friend Emile de Antonio, who knew Johns and Rauschenberg very well, it’s been well documented that they thought that Warhol was just an illustrator. They were very dismissive of him in the early ‘60s, so there wasn’t a true personal connection or a mutual respect. That developed later.

The whole sexuality thing with Johns, Rauschenberg and Warhol wasn’t ever discussed at the time.

Are you referring to their homosexuality, the fact that it was still very dangerous to discuss it? It was still illegal in the US to be gay in the early ‘60s.

Yes, Johns and Rauschenberg never wanted to talk about their partnership and life together. They might not have liked Warhol’s more overt ‘campness’… they were slightly older and it was different for them.

Why do you think Warhol is still relevant?

On one level it’s because they’re still discovering stuff. He left thousands of works, ephemera, archival items — the time capsules are still being opened. Because of the way he made work, he produced inordinate quantities; not simply in a repetitive way, but hyper-specified. The TV shows, the commercial for Schrafft’s restaurant in New York – that in particular has only just been fully restored, and at Tate it is the first time it has been shown in Europe. We just haven’t got to grips with his output.

Didn’t Warhol say he wanted to make one thousand masterpieces per day?

Yeah; he’s so quotable! That’s another reason why he sticks around. Because he published so much of his writing – POPism, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, his diaries – there’s a huge amount of printable, quotable text.

It’s a cliché to say that he anticipated the Internet, but I think he really did predict the idea of short form quotation. Like Twitter, or the idea of talking thousands of pictures per day, which we now take for granted with cameras on our phones, but when he was taking thousands of pictures a day, it would’ve been really expensive. Rolls and rolls of polaroid and 35mm; no one else had the means in the ‘70s.

And he was paying for his experimentation in photography with the money he made through other commercial work…

Yes, commissions, portraits, record sleeve designs, Interview magazine. He understood what it meant to have a prolific production of images before we took it for granted.

He has a live webcam on his grave in Pittsburgh (click here), and you can buy and send him gifts of Campbell soup cans online…

Exactly! Again, it goes back again to the democratisation of art. Tate has its own Instagram feed. We’re responding to what’s out there in the world, we’re not separate from it. There’s no longer a dividing line between the public and what’s deemed to be great art. It’s permeable. We’re trying to keep up with how technology is evolving, and I think he would be at the forefront of that. The way that his mind worked was to pick up on technology at the moment of its initiation.

Like Outer and Inner Space (1965) in the exhibition, with Edie Sedgwick (one of the Factory starlets who suffered from a tragic demise): apparently it’s the first documented use by an artist of using videotape, rather than film. It pre-dates Nam June Paik by a couple of months. By 1965, Warhol was really well known as an experimental filmmaker, and this company making videotape equipment sent him top-of-the-line products to try out. Almost immediately after, the tech became obsolete, as Sony and everyone else made it in a different way, so there are tapes in the Warhol archive that are unplayable. Because he recorded Edie on the videotape, then had her real head in dialogue with this other recorded head, then filmed it on 16mm, it’s captured; it’s a time capsule of this moment of experimenting with all this different media.

If he was still alive, Apple would have sent him the new iPhone as soon as it came out; as he was so immersed in those channels of distribution and capital, he would have been very, very close to how people would have adapted to various waves of the Internet.

It’s fascinating to think about all that videotape work that can’t be accessed, because it’s obsolete and there is no existing equipment to play it on.

People will have to go back through and try to figure it out. I think with the exhibition, we have tried to emphasise that sense of experimentation. He was instantly jumping onto the next thing and incorporating it into his next work. With the Schrafft’s commercial, that was broadcast on television, even though it’s a static shot of an ice cream gently melting with multi-coloured patterns on top of it. The owner of the chain said: “We haven’t just got a commercial, we’ve got a work of art.”

It’s difficult to think of an artist at a similar level of fame who would work on a corporate commercial now…

I know, it’s crazy. I would say someone like Ryan Gander, and his collaboration with adidas, making these trainers that look like they’re dipped in mud. He has had a similar polymorphous relationship to stuff; he’ll do all these collaborations with corporations and will make useable, functional stuff. He may be Warhol’s heir.

What’s your favourite work in the show and why?

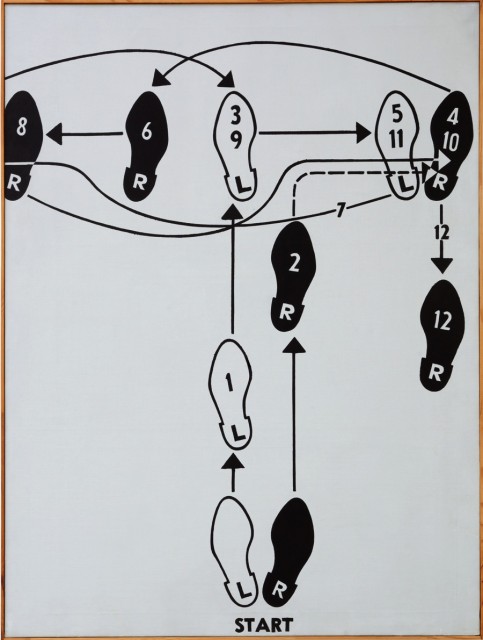

I have to say Dance Diagram [1] [Fox Trot: 'The Double Twinkle-Man'] (1962); I think it’s incredibly forward thinking. I like that it’s not an iconic silkscreen, and it’s at the last point where he was hand-painting his canvases. I like the idea that it is transitional; it’s a result of inexperience but also a cheeky nod to abstract expressionism and painting on the floor. It’s very layered: for something that looks incredibly simple, it has multiple levels of meaning. When people say that they get what Warhol is, and they understand that he is essentially about Pop, mechanical prints, I want to say look at this work – he’s way more complicated than that.

Laura Roberson

Transmitting Andy Warhol continues at Tate Liverpool until Sunday 8 February 2015. Tickets £8/6/5 (includes entry into the Gretchen Bender solo exhibition)

Buy Stephanie Straine’s book, Tate Introductions Andy Warhol, for £6.99 here

Read The Skewed Mirror Of Gretchen Bender by C. James Fagan

Read Field Trip: Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburg by Jose Diaz