An Introduction To Psychogeography

Psychogeography is more than the psychological effects of the urban environment, argues Maisie Ridgway. Here, she explains why the movement has become a political statement, a seizure of power and a joyous mode of play and discovery…

Second right, second right, first left, repeat. You’d be forgiven for thinking that these were simple directions to a final destination, instructions on a treasure map even, but you’d be mistaken. They’re actually a gateway to something much more than ‘X marks the spot’; in fact, the X that marks the spot has never been more irrelevant. The aforesaid instructions are not destination driven, they’re psychogeographical rules applied in order to explore without direction so as to discover the cities that we’ve lived in for years. Romantic writers, Letterists, Situationists and modern writers have all played a part in the development of psychogeography.

In Situationist Guy Dubord‘s 1955 essay Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography, he defined psychogeography as “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals.” Put simply, psychogeography is the exploration of the psychological effects of an urban environment. More than this though, it’s a political statement, defiance of the capitalist system, a seizure of power and a mode of play.

Although psychogeography was not recognised as a term until the early 1950s, the idea has been around in literature for much longer, like in the poetic writings of Poe or Blake. Particularly interesting are Thomas De Quincey’s autobiographical accounts from his work Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1886):

‘’… Sometimes in my attempts to steer homewards, upon nautical principles, by fixing my eye on the pole-star, and seeking ambitiously for a north-west passage, instead of circumnavigating all the capes and head-lands I had doubled in my outward voyage, I came suddenly upon such knotty problems of alleys, such enigmatical entries, and such sphinx’s riddles of streets without thoroughfares, as must, I conceive, baffle the audacity of porters and confound the intellects of hackney-coachmen. I could almost have believed at times that I must be the first discoverer of some of these terræ incognitæ, and doubted whether they had yet been laid down in the modern charts of London. ‘’

De Quincey describes using the stars to guide him home. Having no knowledge of celestial navigation he finds himself in unfamiliar territories, discovering what he believes are streets anonymous to maps, thus reimagining the city in his own eyes.

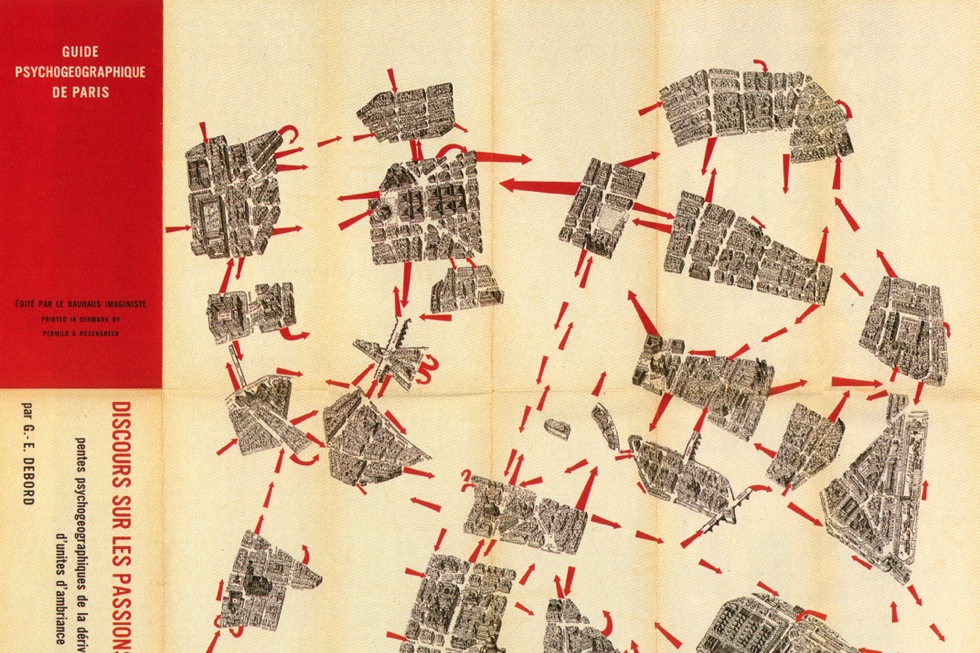

De Quincey’s use of psychogeography inadvertently paints the action as an act of privilege, whereby those with disposable time and income can afford to wander the streets and discover their secrets. The political drive behind psychogeography became more apparent in the 1950s with the Situationists. The situationist movement were staunchly against what they called ‘commodity fetishism’ and invested in the anarchy of play as a mode that defied the capitalist system. One of these acts of play was psychogeography. Exercises typical of a situationist psychogeographer include using maps of different cities to navigate your own, cutting up maps and rearranging them, and the art of dérive or unplanned journeys.

But what relevance does psychogeography bear today? With the increased use of GPS or Google Maps it seems that we have become altogether more and less connected, with the digital world at our fingertips whilst the real world takes a back seat. Journalist and self-confessed pyschogeograher Will Self describes this as an alienation from ‘the physical realities of our city’, a notion that has both social and political implications, particularly for those that dwell in the Big Smoke.

Consider the dependence upon systems external to the individual mind or body to navigate space; becoming unaware, for example, of how we have reached our destination even during regular journeys because of a reliance on GPS. Debord goes further and suggests that cities are capitalist designs made to accommodate the increased sale of automobiles, and exploit the need to travel from A-B, thus the increased inability to navigate our surroundings individually contribute to the infiltration and dominance of capitalist culture.

Walking also has gendered implications. In her 2006 book Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit writes about walking in San Francisco: “I was advised to stay indoors at night, to wear baggy clothes, to cover or cut my hair, to try to look like a man, to move someplace more expensive, to take taxis, to buy a car, to move in groups, to get a man to escort me – all modern versions of Greek walls and Assyrian veils.” Thus she ascertained that “many women had been so successfully socialised to know their place that they had chosen more conservative, gregarious lives without realising why. The very desire to walk alone had been extinguished in them …”

How then does walking aimlessly attempt to address these problems? Most apparent is the idea that getting lost in a city is a sure fire way to learn how to get found again. More than this though, walking is time spent outside of the realms of profit, one is neither working nor buying. This in itself opposes uniformity and is further reinforced by the creative and play aspects of psychogeography. Architectural theorist Robert Harbison says that: “To put a city in a book, to put the world on one sheet of paper — maps are the most condensed humanized spaces of all… They make the landscape fit indoors, make us masters of sights we can’t see and spaces we can’t cover.” So, creating or manipulating maps in order to navigate space is a form of empowerment that allows autonomy over our environment and praises discovery over dictation.

In present day, the term psychogeography covers more than navigation, play and the city. Additional impetus is placed on one’s capability to fulfil a journey. Self argues that a common example of a contemporary city dweller is one that is “is unable to experience being alone in place itself: not knowing where [they are], and too unfit to travel across appreciable portions of the city by [their] own motive power, [they are] condemned to a socialised spatial existence”. The inability to travel a distance by foot is a stifling factor that contributes to a lack of personal empowerment.

There are, however, current examples of psychogeographers in action. Run Dem Crew is a community of runners founded by poet Charlie Dark. Their aim is to run fast, strong and far whilst exploring the city of London. Urban explorers also provide examples of modern psychogeographers who access prohibited spaces — like photographer Peter Costello — heaving forgotten urban landmarks back onto our maps. Psychogeography exists, and has existed in many forms but never has it seemed more relevant. In an increasingly apathetic society there is a need to revive the joys of discovery, play and self-empowerment. So have a ramble, take a walk, and get lost. The world’s your oyster or whatever shellfish you want it to be.

Maisie Ridgway

Read other TDN articles on psychogeography here

Images, from top: Guy Debord 1957: Psychogeographic Guide of Paris. Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit, Penguin Books (June 1, 2001)