An Evening With Julian Cope

One-part Viking, one-part shaman, one-part biker, and one-part rock star: Nathan Richardson spends an ‘incredible’ and ‘absurd’ evening with Julian Cope…

Julian Cope, as an artist, stands alone. He is the only person to have appeared on the front of Smash Hits and written books about Neolithic Europe. In the 1980s, he had hits with the Teardrop Explodes, but the group split in 1983, and he has since explored a solo career, dropped the pop star fantasy, and delved into the avant-garde. Now, at the age 56, he has published his first novel. It is called One Three One. It is, he says, “a time-shifting Gnostic hooligan road novel”, and on Monday he returned to Liverpool, where his career began, to talk about the book at the Unity Theatre.

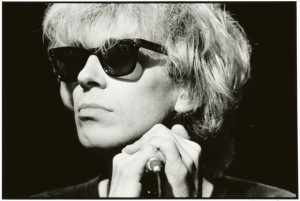

He is introduced by Lee Brackstone, an ambassador from Faber, his publisher, and takes to the stage dressed as if he is ready for battle. He wears steel gauntlets, a black leather sleeveless biking jacket, and on his head rests the hat a Brigadier General in United States Air Force would have worn in 1968 Vietnam. (I am no expert on military headwear; he talked a recent interviewer through his outfit, which doesn’t change from day to day.) He has long, straw-like hair and a recent acquisition to his make up: a thick, bushy beard. He looks one-part Viking, one-part shaman, one-part biker, and one-part rock star. He does not look as if he is about to promote a novel.

Cope is a fascinating interviewee. His minds works rather like Wikipedia – he starts on one subject and very quickly turns onto something else, leaving his audience both perplexed and amazed. He has an incredible, enquiring, absurd imagination. The novel, he tells us, begins with Rock Section, his hero, quite literally shitting himself in the toilet of an aeroplane bound for Sardinia. He is a former rave musician returning to the island where his hooligan friends were killed during Italia ’90. Rock Section is from the Nottinghamshire mining village Eastwood, home to D.H. Lawrence, who himself spent time in Sardinia. Lawrence, Cope said in a BBC interview, had the “last great comment on England.” It is a book that covers many grounds, many times, places, and people. It is, after all, a time-shifting Gnostic hooligan road novel.

But beneath the fantastical situations (in the book, for example, Van Morrison is dead, but Jim Morrison is alive) he seeks to explore great truths. Something he stresses throughout the evening is that he only wrote the novel because he felt he had to. Like Lawrence, he is offering a commentary on Western Culture. Sardinia is an enclave, looked on with suspicion by mainland Europeans. In Italia ’90, England, Ireland, Netherlands, and Egypt found themselves in the same group. With those countries all prone to hooliganism and excessive drinking, the authorities, fearing trouble, fixed all group games to stadia in either Sardinia or Sicily, away from the mainland. Lawrence was a radical, misunderstood by his generation, Cope is perhaps much the same.

Sardinia, the enclave, perhaps represents us, the masses, and our relationship to the State. He is, he tells us, still working through the frame punk-rock: that anybody can do anything and that the State is irrelevant. One Three One channels his interests and enthusiasms, his views and perspectives, and, incredibly, it somehow works.

The writer Stewart Home, who has committed himself to pushing the boundaries of literature, has argued that the only way to write a truly revolutionary novel today is to write a bad novel. Bad does not necessarily mean E.L. James, but bad in that it does not appeal to the Bourgeois, Booker-loving, Middle English readership. For them, a novel is something to read besides a swimming pool; it is to be breezy, and entertaining. They might see themselves in some of the characters, and it all reaches a happy, satisfactory conclusion, and they can then get on with their lives.

A bad novel challenges this. It is disruptive. “The novel,” Home says, “is a paradigmatically bourgeois cultural form, so a good novel is inherently reactionary — only bad books can be revolutionary.” One Three One, is in this sense, with its manic characters, its wandering plots, its marriage of prose and poetry, its 12” record that accompanies the novel and features original songs his characters have “written”, is a ‘bad’ novel. But that’s good.

This novel, as Cope has done with music, pushes the boundaries. It does not conform. Interestingly, the Booker Prize went nowhere near it. Perhaps, in their eyes, a novel written by a rock star can scarcely be called a novel at all, but One Three One, I feel, will delight and intrigue readers for years.

Nathan Richardson

More from Nathan here

One Three One is available from Faber now, RRP £14.99

See more upcoming Waterstones events at Liverpool ONE and around the rest of the UK here